March 27, 2003

You turn on the tube, and there he is, giving yet another speech. But after a couple of minutes, you start to realize this isn’t just any old Chávez speech. “I’ve had it, frankly,” he says, “the state redistribution system is just not working here.” Weird. You watch on. “The way we’ve been going about distributing the oil money is all wrong, and the time is ripe for a radical rethinking. From now on, the State is just going to redistribute all of Venezuela’s oil revenue equally to each and every citizen. Just send a check to each person with their share. After all, you can’t possibly do a worse job of administering it than we have, so we’re just going to divvy up the kitty and let each of you decide how to spend your share.”

President Chávez did not, of course, say this, nor will he…but just imagine for a second he did. How much money would each Venezuelan get? Guess. Remember now that this is (or was, until recently), the world’s fourth leading oil producer…and it’s a relatively small country, you’d only be splitting the loot 23 million ways. So how much do you think each person would get?

Pick a number.

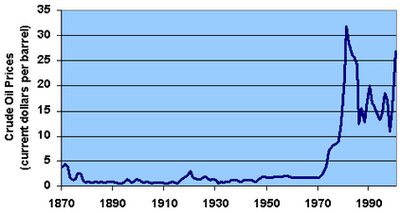

The thought exercise is Gerver Torres’s, who has been putting it to audiences all over the country for years now. The answers he gets are a real eye-opener. The average response is about $100,000 per capita, yearly. Often he gets far higher estimates. (How much did you guess?) Very rarely do Venezuelans come even close to the actual figure, and almost always they’re shocked to the point of utter, stammering disbelief when they hear it - about $1/day…the price of a plain arepa.

I heard Gerver give this little spiel this morning, at a forum on corruption and how to fight it put on by Mirador Democrático, a local anti-corruption NGO. Gerver, a one-time communist activist turned World Bank technocrat turned right-wing pundit, makes a powerful case that Venezuelans’ fundamental misunderstanding of the scale of their oil wealth makes it impossible to have a serious debate about corruption in this country. If you live in a miserable shantytown with no running water, but you’re convinced that your fair share of national income is in the hundreds of thousands of dollars yearly, then nothing anyone says has the slightest possibility of convincing you that you’re not being skinned by some shady cabal of corrupt plutocrats. All that money has to be going somewhere, right? And you’re not seeing it. Ergo…

Gerver is at pains to explain that the misconception runs right across Venezuelan society – this is not about very poor, uneducated people having nutty ideas. Running his little mental exercise with audiences from widely differing social backgrounds, he gets more or less the same responses every time. University educated Venezuelans are just as taken with the myth of fantastic oil riches as the destitute.

The point was powerfully driven home just a few minutes later when opposition congressman Conrado Pérez took to the podium. Pérez is the chairman of the National Assembly’s main corruption-busting body, the Comptrollership Committee. According to an old parliamentary tradition here, the biggest opposition party in congress always gets to pick the chair of this committee - in this case, it's Acción Democrática. The Comptrollership chair is perhaps the most influential opposition-controlled post in the National Assembly, so you'd think they'd try to get someone good for the job, someone bright and sophisticated and articulate and willing to learn his shit and make the best out of the job.

Oh, but no. Conrado's speech seemed specifically designed to demonstrate even top-level political decision-makers here haven’t the slightest clue of what they’re talking about in terms of oil wealth, corruption, and the relationship between the two. Top heavy with almost infantile clichés, Pérez’s speech was astonishing in terms of sheer ignorance displayed.

His inability to understand basic concepts about corruption seemed almost staged to prove Gerver’s point. Literally minutes after Gerver had finished delivering his devastating critique, we heard the top congressional anti-corruption official argue that if corruption was stamped out completely, the funds freed up would be enough to pay off the entire National debt (about $45 billion, all in), build 100,000 low-income homes, 5,000 schools, and 300 outpatient clinics, not to mention thousands of kilometers of rural roads, and a monthly $18 “school attendance payment” to encourage low-income families to send their kids to school.

I admit I haven't the slightest idea as to what kind of delusional math got him to those figures, but they are nothing short of laughable. The tirade made it plain that this man simply didn't understand a single word of what Gerver had just said! It was amazing to behold - it's not that the guy's understanding of corruption is spotty, it's that Conrado Pérez knows nothing, understands nothing, and can be expected to contribute nothing to the fight against corruption. Still, when you go to the National Assembly and ask them to investigate a corruption allegation, it’s his desk your request eventually ends up at.

[Later, he managed to keep a straight face as he told the auditorium that while AD had had some problems with corruption in the past (the understatement of the decade), that these days 99.99% of adecos are squeaky clean - a claim so transparently false it actually elicited some audible snickering from the audience. The claim only reinforced my belief that adecos are genetically incapable of a straightforward mea culpa...how can you expect them to do better in future if even today they refuse to own up to even the most blatant of their excesses?]

Good grief…hearing this babbling moron talk this morning depressed me to no end. It struck me that the morning conference captured perfectly Venezuela’s basic problem with development. It’s not that we don’t have bright, articulate, talented, intellectually honest people working on the issues of the day. We have plenty! It’s not just Gerver – who is a national treasure – it’s every single other speaker at that forum. People like Rogelio Pérez Perdomo of Iesa and Albis Muñoz of Fedecámaras and everyone else who spoke. Each set out a sophisticated, realistic, thoughtful contribution to the debate on corruption, each had clear and sensible ideas as to how it works and how it ought to be fought. But all have one other thing in common: they have no political power whatsoever, nor any real prospect at getting some.

Meanwhile, the one guy in an institutional position to do something about corruption is a bona fide imbecile.

It’s shocking, really, and deeply sad. The country has problems. The country has people with clear, serious, pragmatic ideas about how to solve those problems. But the country can’t seem to put the two together at all. For some baffling reason, only the clueless get power, while the clued-in are systematically ghettoized into academia or the private sector.

So forget about the angry tirades in the newspapers. Disregard the neverending, terminally boring ideological cat-fights between chavistas and antichavistas. The country's real problem is a shocking, almost limitless tolerance for mediocrity in the public sector. Somehow the gate-keepers to the key positions of political power and influence have no problem at all putting the likes of Conrado Pérez in leading roles. Doubtlessly, he’s earned his stripes by showing unending, canine obedience to AD party leaders, and they’ve rewarded him with a plum appointment. It makes no difference at all to them that he generates the intellectual wattage of a cucumber – he’s their cucumber.

Meanwhile, the Gerver Torreses of the world are reduced to going door-to-door, university-to-university, NGO-to-NGO desperately seeking someone, anyone who will value and reward their commitment to studying key problems honestly, meticulously, and seriously.

What’s sad is that it’s always been like this. It was like this before Chávez got elected, it’s like this now and, depressingly, it very much looks like it’ll be like this after he’s gone. Ultimately, the government/opposition fault-line conceals a far more relevant divide in Venezuelan politics: the huge chasm between the Mediocrity Party and the Excellence Party. The all-consuming fight between government and opposition boils down to a factional struggle between the right and the left wings of the Mediocrity Party. The real tragedy, though, is that Venezuelan society seems to have developed fail-proof mechanisms to make sure the Excellence Party never reaches power.

March 24, 2003

Life without Janet

Like everyone who knew her, I was shocked and saddened to hear of Janet Kelly’s passing this morning. Janet was that rarest of public figures in Venezuela – truly democratically-minded, fiercely intellectually honest, allergic to extremism, willing to take uncomfortable positions on principle, and gleefully irreverent. Both sides in the political conflict mistrusted her, because she refused to mortgage her brain - or her principles - to either of them. In this, she was truly extraordinary, and in much more than this.

American-born, Janet had lived here since finishing college in the 70s, and became that most endearing of characters: the thoroughly venezuelanized gringa. Though she could never shed her stereotypical American accent, you only had to spend 10 minutes with her to see that Venezuelanity had seeped into her blood. Janet had options, but she chose to make Venezuela her country, and how can you not love that?

At the same time, Janet was such a wonderfully warm, kind person. Weird as hell, too, sure, but truly other-oriented. Looking back now it’s hard not to think that what we’d seen as quirkiness could have been the outward signs of the disease that ultimately claimed her life, depression. It’s too sad to think about, really, that someone like Janet could have taken her own life. Just terrible.

It’s not just a blow to the country, and to English-language publishing in this town, it’s also a terrible loss for this blog. Janet was my favorite reader – always eager to respond with humor, insight, and real appreciation, critical appreciation, which is the best kind. Re-reading her emails now is wrenching – all of that good will that I only reciprocated with a quick “thanks for writing in,” instead of taking the time to really express how much it meant to me that someone of her stature was taking the time to read, examine and comment on my crappy little web-site.

It’s such a sad day. This country needs more, many more Janet Kellys…instead we’ve lost the only one we had.

March 20, 2003

About the Author

After four years as a freelance journalist in Caracas, I've run off to become a doctoral candidate in innovation economics at the United Nations University's Institute for New Technologies in Holland.

I'm working on a dissertation on the impact of WTO rules on developing countries' ability to implement effective technology policies. Yes, I think that's interesting.

Blog email goes to

caracaschronicles at fastmail.fm

Academic email goes to

toro@intech.unu.edu

Personal email goes to

franciscotoro at fastmail.fm

March 19, 2003

There's nothing to blog about out of Caracas, but I am becoming frankly obsessed with the stunning writing going on at Where is Raed? so I'm just going to republish his writing today. Last night, I had nightmares that this kid got hurt in a bombing raid. I woke up in serious distress, I felt like I'd lost a friend. Intense.

From Salam's blog:

A couple of weeks ago journalists were exasperated by that fact that Iraqis just went on with their lives and did not panic, well today there is a very different picture. It is actually a bit scary and very disturbing. To start wit the Dinar hit another low 3100 dinars per dollar. There was no exchange place open. If you went and asked theu just look at you as if you were crazy. Wherever you go you see closed shops and it is not just doors-locked closed but sheet-metal-welded-on-the-front closed, windows-removed-and-built-with-bricks closed, doors were being welded shut. There were trucks loaded with all sort of stuff being taken from the shops to wherever their owner had a secure place. Houses which are still being built are having huge walls erected in front of them with no doors, to make sure they donÕt get used as barracks I guess. Driving thru Mansur, Harthiya or Arrasat is pretty depressing. Still me, Raed and G. went out to have our last lunch together. The radio plays war songs from the 80Õs non-stop. We know them all by heart. Driving thru Baghdad now singing along to songs saying things like Òwe will be with you till the day we die SaddamÓ was suddenly a bit too heavy, no one gave that line too much thought but somehow these days it is sounds sinister. Since last night one of the most played old ÒpatrioticÓ songs is the song of the youth Òal-fituuwaÓ, it is the code that all fidayeen should join their assigned units. And it is still being played.

A couple of hours earlier we were at a shop and a woman said as she was leaving, and this is a very common sentence, ÒweÕll see you tomorrow if good keeps us aliveÓ Ð itha allah khalana taibeen Ð and the whole place just freezes. She laughed nervously and said she didnÕt mean that, and we all laughed but these things start having a meaning beyond being figures of speech.

There still is no military presence in the streets but we expect that to happen after the ultimatum. Here and there you see cars with machine guns going around the streets but not too many. But enough to make you nervous.

The prices of things are going higher and higher, not only because of the drop of the Dinar but because there is no more supply. Businesses are shutting down and packing up, only the small stores are open.

Pharmacies are very helpful in getting you the supplies you need but they also have only a limited amount of medication and first aid stuff, so if you have not bought what you need you might have to pay inflated prices.

And if you want to run off to Syria, the trip will cost you $600, it used to be $50. itÕs cheaper to stay now. anyway we went past the travel permit issuing offices and they were shut with lock and chain.

Some rumors:

It is being said that Barazan (SaddamÕs brother) has suggested to him tat he should do the decent thing and surrender, he got himself under house arrest in one of the presidential palaces which is probably going to be one of the first to be hit.

Families of big wigs and ÒhisÓ own family are being armed to the teeth. More from fear of Iraqis seeking retribution than Americans.

And by the smell of it we are going to have a sand storm today, which means that the people on the borders are already covered in sand. Crazy weather. Yesterday it rains and today sand.

:: salam 3:12 AM [+] ::

March 18, 2003

I’ve been somewhat delinquent about posting lately. In part, the news out of Venezuela has gotten really boring. Also in part, I finally got satellite TV in my house, and CNN and the BBC are much more compelling right now. Mostly, though, there’s just this forlorn feeling hanging in the air…this despondency, this anger both at the government and the opposition leadership at the same time. The whole country is up a creek without a paddle at the moment, and it’s just too sad to think about, much less write.

Plus, with the world-historical transcendence of events in Iraq, it’s just hard to feel that the latest he-said-she-said on Globovisión is even close to being worth writing about. The entire architecture of post-war international security is going up in smoke and down here we’re consumed in these ridiculous fights about when you’re allowed to start gathering signatures for a referendum. It’s just pathetic.

The upshot is, I think they should just give journalists a few months off here, let us go hang at the beach until the halfway point in Chávez’s mandate rolls around and serious politics resumes. When the time comes, on August 19th, then we’ll know what’s what. Then we’ll know if he’s serious about letting us vote, or if the delaying games will go on indefinitely. We’ll either toss him out through the ballot box or know, finally, for certain, that we’re dealing with an out-and-out dictator, and adapt our tactics accordingly.

For now, all we can do is watch, wait, and be sad about the dismantling of our institutions, our economy, and our freedoms. We might have to fight a minor tactical battle now and then, we might even win a couple, but the fundamentals won’t change until August. So, unless something truly worth writing about happens between now and then, I suppose the blogging will be slow between now and then.

For now, there’s not much to do but hope the civilians of Iraq and the safety of the world system escape what’s coming more or less intact.

March 15, 2003

About the Author

I am a Ph.D. student in Innovation Economics at the United Nations University's Institute for New Technologoes in Maastricht, the Netherlands.

I used to be a freelance journalist/magazine editor in Caracas.

Blog email goes to:

caracaschronicles at fastmail.fm

School email goes to:

toro at intech.unu.edu

Personal email goes to:

franciscotoro at fastmail.fm

Please direct all anguished rants, appalled tirades, horrified lectures and mentadas de madre to the email address on the right.

It's perfect

Carlos Ortega, the country's top labor leader and the brain-behind-the-national-strike, has chosen exile over jail (can't blame him.) Carlos Fernández, his business federation buddy, sits under house arrest. Two days ago, Ibéyise Pacheco, the firebreathing antichavista muckraking journalist, was nearly arrested by the State Security Police (Disip) and went into semi-hiding. The government crack-down appears comprehensive and likely to get worse...it's great!

Yeah, yeah, I know, the onslaught is an appalling, deep and flagrant violation of all sorts of basic democratic principles, an afront to human dignity and civil rights, yaddi yadda, all that. But from a brutally detached, real politik type outlook, it's a godsend for moderates in the opposition camp.

First off, because it's having a deeply negative impact on perceptions of the government abroad. I mean, you know and I know that Carlos Ortega is nearly as narcissistic and authoritarian as Hugo Chávez, but the foreign press is still bound by certain standards of professional ethics to treat him as a proper opposition leader, persecuted for his convictions. You and I know that Carlos Ortega led the entire opposition movement up the garden path, diving headlong into a mad general strike that was never part of a proper plan for getting rid of the government. You and I know that Carlos Ortega is responsible for driving hundreds of businesses into bankruptcy and tens of thousands of workers into unemployment, that he never had a plan B, never thought beyond fomenting chaos, disorder, and economic collapse and hoping all of that would lead someone, somewhere, somehow to shove the government out of power. But as far as international public opinion is concerned, he'll now be retroactively portrayed as a brave, embattled pro-democracy leader persecuted for his beliefs. So it's perfect: this dangerous lunatic is taken out of action, shoved well away from the center of opposition decision-making (where he never should've been in the first place) and, on top of that, we get international sympathy and support too.

Something similar happens with Ibéyise Pacheco - the dean of antichavista extremism in the Caracas newspaper world. Journalists here know all about how the sausage is made over at Asi es la noticia - the embarrasingly bad, El Nacional-owned tabloid rag she "edits." For years Pacheco has been shoving her appalling brand of pseudojournalism down the throats of unsuspecting readers. Her insufferably prima donnaish persona, her galling willingness to stretch, distort or invent to damage her political enemies, and the shrill, near-hysterical tone of her antichavismo have probably done as much damage to the practice of decent journalism in this country as any number of lunatic rants against the press by Chávez. Now, with this travesty of journalism on the run, readers are spared, Pacheco is disempowered, and decent journalism wins that much more space. Meanwhile, foreign governments will be horrified to hear about the prosecution of a "dissident journalist" (such a noble-sounding moniker!) and the government will see one more bit of plaster fall from its democratic façade. It's a godsend!

Though Carlos Fernández, the Fedecamaras house-arrestee, is not as objectionable as these two other characters, you can certainly argue that moving against him the government has freed the business federation of an especially ineffective and unimaginative leader, only to leave Fedecamaras in the hands of his one-time right-hand woman - Albis Muñoz, who's far brighter, more articulate, and more promising as a leader. She's been so dashing in her post-arrest press appearances, some people are starting to think of her as "presidentiable." She probably never would've reached that position were it not for her boss's arrest - yet another unforeseen benefit of this latest wave of repression.

Am I the only one who sees a pattern here? Though it's obvious that only rank authoritarianism motivates the government to move against these opposition radicals, the upshot is that the crack-down is clearing all kinds of dead wood from the opposition deck. The best you could say about the people being persecuted now is that they had clearly failed; the worst, that in their mindless radicalism and immediatism they replicate much of what they decry in the government. Though these radicals were clearly setting back the struggle to unseat the lunatic president, moderate opposition activists had no way to get rid of them. Now, in a delicious own-goal, the government does it for them, in the process not only improving the quality of the opposition's leadership but also giving itself a big, bad, black eye in terms of international standing.

It's perfect.

March 9, 2003

Five short essays about Venezuela

I. Too flaky to be a communist

It's become such a cliche, one foreign journalist actually admitted to me he just cut-and-pastes it into his stories. "The opposition accuses Chávez of governing like a dictator and taking Venezuela towards communism." OK, the dictator part is pretty straightforward. But Chávez a communist?!

To my mind, it amounts to an unconscionable slur against communists everywhere. After all, communists had an ideology, a coherent view of the world, and a thought-out plan about how to make it better. That plan turned out to be wrong, even monstrous, but for decades it had at least some intellectual currency. It offered a vision of a better future for the people who needed it most, and it was grounded on a philosophy that, like it or hate it, was sophisticated, nuanced, and had a long and illustrious intellectual tradition behind it.

The Chávez experiment couldn't be further removed from that. As my uncle Pepe Toro argues, in some senses chavismo is much closer to fascism, because it's really a doctrine about how to obtain and retain power, not about what to do with it. Chavismo might be influenced by marxism, yes - it certainly borrows marxist ways of describing the world - but the overall package is far less coherent than marxism.

Take, for instance, Chávez's relationship to the private sector. In recent months, it's become clear that he's determined to crush it, to drive private entrepreneurs out of business en masse rather than allow them to function as a hotbed of opposition to his regime. This is obviously not what you'd call neoliberalism. But does that make the government communist?

Think of it this way, when Salvador Allende was elected in Chile in 1970, he knew exactly what the road ahead held. As a Marxist, he was committed to ending the control of the capitalist class over the economy, yes, but not as an end in itself. The destruction of Chile's private sector was just what needed to be done in order to collectivize the Chilean economy, to put the means of production in the hands of the proletariat, to use the lingo. A long tradition of Marxist thought pointed to this as a necessary step in the way to liberating the working class and improving their material position. You might find Allende's road-map to a better society aberrant - as I do - but you can't deny he had a plan: he wasn't just wrecking private businesses for the sake of the wrecking itself.

President Chávez has also explicitly set out to destroy the private sector, but unlike Allende he's never proposed any sort of alternative to replace it with. He's been perfectly blunt in saying that the point of the recently announced exchange and price controls is to destroy the traditional private sector. But unlike a marxist, he's not interested in collectivization or mass-nationalization, he has no plan for remaking the nation's economy once the capitalist classes have been done in.

The reason, I think, is that his assault on the private sector is not in fact an economic strategy. Like everything else in chavismo, the onslaught is a political act, designed to undermine a source of political dissent, to dump that particular pebble from the president's shoe, without any reference to anything like a plausible plan for what comes next.

How will the hundreds of thousands of families that rely on income from their private sector jobs make a living after those companies go under? How will the state meet even its most elementary spending necessities after it's through disemboweling the companies at the center of its tax base? What will Venezuelans eat once the companies that produce most of their food have been driven into the ground, with nothing to replace them? Chávez has no answers to these questions. Nothing in his behavior indicates that it's even remotely concerned about these issues. He understands the private sector's opposition as a purely political problem, an unacceptable challenge to his power, and he's just not prepared to tolerate that.

II. Out-argentinaing Argentina.

The consequences for the country are terrible, devastating, hard to overstate. Credible institutions like Deutsche Bank and GM are forecasting a 20% drop in GDP this year - that's almost twice as much as Argentina's contraction last year, and you know what happened to people there. In a country like Venezuela, an economic contraction on that scale simply means people go hungry. Maybe not starvation hungry, but definitely mass-scale undernourishment hungry.

It's already happening. Every month Cenda, a Think Tank associated with the Venezuelan Labor Movement, calculates the cost of a basket of basic foods. The index is made up of the basic staples in poor Venezuelans' diets. Right now, the cost for a family of five stands at $210 - well over the $125 minimum wage. In short, it takes two adults in full-time minimum-wage work to meet even the bare-bones basics of nutrition.

The problem is that households with two adults in full-time, minimum wage work are becoming a rarity here. The unemployment is running at 17% - and that's according to the usually overoptimistic official stats, private firms think 20% or more is probably closer to the mark. Worse still, just over half of working Venezuelans earn a living in the informal economy, sometimes referred to as the "gray market." Most are "self-employed" as streethawkers, odd-job repairmen, or day-laborers - they make a living entirely outside the legally sanctioned employment system. They're not covered by any of the nation's employment protection laws - they have no unemployment insurance, no legally mandated vacation, no provision in case of disability, and of course, no one to guarantee them they'll earn the minimum wage. According to a recent Catholic University study, 90% of informal workers make less than the minimum wage.

To put it bluntly, millions of Venezuelan families can't afford to eat properly right now. To a huge and rapidly growing portion of Venezuelans, "food" means white rice, arepas (little corn flour patties), salt and margarine - once or twice a day. They can't afford anything else.

Cenda, the think-tank, also calculates the monthly cost of a Basic Goods and Services basket, which includes not just food, but also other basic consumption items like clothes, basic school supplies for kids, rent, medicines, electricity and water bills, the bare-bones basics for a modest but reasonable existence. By Cenda's reckoning, a family of five needs $665 a month to cover this basic basket. And what percentage of Venezuelan households earn $665 or more each month? A mere 6.4%. You read that right. After four years of revolutionary government for the poor, 93.6% of Venezuelans can't afford even the basics - a crushing indictment, if you ask me.

It's a dramatic situation. It's not even that Venezuelans' purchasing power is stagnant, it's that it's in free-fall. Venezuelans haven't been this poor since the late 50s. This is not a Guatemalan situation where people are poor because they've always been poor and have never known anything other than grinding poverty.

Think of it this way - from the 60s to the early-80s, per-capita purchasing power in Venezuela was higher than in Spain. This used to be an up-and-coming country with a large and expanding middle class...a place poor spaniards might reasonably want to emigrate to.

(Many did - poor suckers - and now their children are lining up outside the Spanish consulate to get mother-country passports for the return-migration journey.)

Even more traumatic than the experience of mass-poverty is the experience of mass impoverishment. A very large chunk of the 94% of Venezuelans who are now poor know what it's like to lead a middle-class lifestyle. They used to have stable jobs, they used to be able to afford vacations and nights out at restaurants and theaters and things like that. They went to university. They might be children or grandchildren of peasants, but they were implicitly promised the comforts of a middle-class lifestyle. And that promise has been cruelly ripped away from them.

Now, obviously, you can't lay the entire blame for this hideous situation on Chávez. The Venezuelan economy had been in decay for two decades before he took over. But the rate of impoverishment has quickened significantly since he came into office. And just about everything Chávez has done in four years has tended to accelerate the decline - including, crucially, picking an absurd fight with the business community. When the leader of your country spends most of his time dreaming up ways to screw the people who create the wealth and generate the jobs, is it any wonder most people's get much, much poorer? The truth is that chavismo has never had anything you could reasonably call a serious economic strategy.

In its place, what they've offered is turbocharged, unadulterated voluntarism.

III. Will Power

For Chávez, as for any number of megalomanic dictators before him, the sheer will to do something is enough to achieve it. "If the coupsters don't want to make corn-flour (for arepas)," Chávez said recently, "then we'll join together in cooperatives and make the flour ourselves!" If people want to band together and replace Venezuela's private agroindustrial apparatus with a coop, what's to stop them? Technical problems, supply-chain logistics, inventory management, financing needs, sanitary standards, industrial expertise all these things are trifles when matched to the indomitable will of the revolutionary masses.

If you've read about Mao's great leap forward, or Fidel's plan for a 10 million ton sugar harvest in 1970, you can recognize this as a an ideological re-run. Voluntarism run amok is the sure-fire marker of megalomanic authoritarian leadership. I can think of no instance when such a view of the world hasn't led to a huge human catastrophe.

Voluntarists, especially leftish voluntarists, are deeply suspicious of anyone who claims specialized technical know-how or any sort of managerial expertise. Claims of special technical expertise are seen as an arrogant assertion of unjustifiable social privilege, a kind of upper-class ruse to keep the oppressed quiescent. The result is not just disdain towards specialized know-how, but an actual aversion to it, a kind of horror of expertise. '

Venezuelans reading this can probably think of 2 dozen examples of what I'm describing here. But for my money, the most tragic manifestation of this tendency in Venezuela has been in PDVSA - the state owned oil company that provides the government with half its income and the country with 80% of its export earnings. When four fifths of the company's employees joined the General Strike back in December, the government made no attempt at all to negotiate with them, much less to try to woo them back. Instead, it slammed them as saboteurs and coupsters, and fired 16,000 of them - nearly half the company's payroll. Among the fired were literally thousands of highly specialized workers, technicians, engineers, geologists, seismic experts, rig specialists, managers, executives - hundreds of thousands of staff-years worth of experience and know-how on how to run one of the world's largest energy companies.

Chávez simply never saw why he might need any of them. After all, how hard can it be to run a transnational oil company? If the will is there, anyone could do it. Isn't that what the revolution is about?

So out went the people who knew something about how to run the company, in went the ideologically driven chavista "managers." The results have been truly disastrous - three and a half-months after the oil strike started, Venezuela is still producing under half the pre-strike levels. Government oil revenue is projected to drop by half on last year even by the government's own estimates. The costs of this contraction in terms of the horrendous retrenchment it will cause in government spending and the brutal knock-on social effects that will have, largely explains why we're on the verge of an Argentine scenario. Yet Hugo Chávez won't even consider negotiating the strikers' return.

Instead, he's working on jailing their leaders.

IV. Mr. Bean Energy Corporation

Numbers alone don't come close conveying the scale of the disaster in the oil industry, though. They also don't show the way chavista voluntarism has led directly to that disaster. To get a feel for the way PDVSA is being destroyed you really need to hear some of the incredibly alarming anecdotes coming out of the industry these days.

The Eastern Shore of Lake Maracaibo is one of the main oil-producing regions. The region is, of course, full of companies small, medium and large that work with PDVSA. The state giant hires them to perform various highly specialized tasks, quite often very specific, sophisticated work that PDVSA doesn't want to bother with. For instance, a friend of mine who lives out there tells me about one company she's in touch with that services drill-bits. That's all they do. It might seem somewhat pedestrian, until you realize that oil exploration drill bits are actually quite high-tech components - made to operate at fantastic depths, under very high pressure and at incredible temperatures - so keeping them in operating condition is a fairly sophisticated task.

Last month, a group of new (i.e. chavista) PDVSA managers approached this drill bit contractor's management to ask whether they would be interested in an all-inclusive ("turnkey" in the lingo) contract to operate an entire oil field, from logistics and engineering to extraction, well management, and even payroll. The contractor's managers weren't sure if they were joking at first. It was the equivalent of asking a kid with a sidewalk lemonade stand to be chairman of the Coca Cola Company - after all, they're both in the soft drink business.

Apparently, the people who now run PDVSA saw the contractor's name in internal documents, and figured, "hey, these guys are oil sector contractors, maybe they can run this oil field for us," so they just asked before making any effort to ascertain whether they were in anyway qualified to do so. The contractor managers were shocked and, well, just freaked out: they had been working with PDVSA for over 25 years, and suddenly they find themselves dealing with managers who plainly haven't the slightest clue of what it is their company does.

There's more where that came from. Much more. One of the most shocking stories comes out of Carito oil field in southern Monagas State - one of the youngest, most productive oil producing areas in the country. As a relatively young field, it's quite easy to get oil out of Carito. That fact put it high on the new PDVSA's target list for restarting production: it was clearly one of those elusive "easy fields." In fact, the field is so easy because it has plenty of natural well pressure. That means you don't need to do anything to get oil out of it - it just comes to the surface on its own, like the oil in cartoons. But anyone who knows anything about oil knows that you need to start reinjecting natural gas and water back into the field to keep pressure adequate when a field is still young - that's standard operating procedure because it just saves all kinds of trouble down the road.

The problem is that Chávez fired everyone who knows anything about oil production in PDVSA. The new management apparently either didn't know how to operate the reinjection process, or couldn't be bothered with it. So they started pumping oil out of Carito on its own natural pressure - without any reinjection.

The problem is that the chemical makeup of the crude in Carito is such that if pressure drops below a certain critical level, a chemical reaction starts to take place that literally turns the oil into asphalt. Once that happens, there is literally no way to ever get it out again. International contractors who operate in the region estimate in private that up to a billion barrels of oil in the region could be permanently lost due to the mismanagement of the Carito field.

Just mull over that number for a second - at the current $32 to the barrel, that's $32 billion, about the equivalent of Venezuela's entire foreign debt. Flushed, down the drain, through the incompetence of PDVSA's new and improved chavista management.

It's an incredible outrage.

Then there's the story of an international company (which I can't name) that was approached by some new PDVSA managers in Caracas who asked that they do several million dollars worth of service work for PDVSA. The foreign company was thrilled by the deal, and told the managers "sure, lets work out a contract and get on with it." The PDVSA managers dissented. "The thing is," they said, "we're in a real emergency situation here, we really need to get this work done right away. Why don't you go ahead and start, and we'll work out the contract later." My source for this story wasn't so sure whether to laugh or cry as he told me about this. The people now running PDVSA simply had no idea of what an incredibly stupid, amateurish, unacceptable, idiotic request that was.

Trying to collect themselves, the foreign company representatives tried to explain how they would, y'know, all get fired if they even dared to propose something that unprofessional back home, how headquarters in Silicon Valley would laugh them out of the room if they brought it up as a serious possibility. I mean, it's a fairly basic thing, right, it doesn't take an MBA to figure this one out. First you sign the contract, then you do the work. You'd think they could wrap their feeble little brains around that one, wouldn't you?

You'd be wrong, the new PDVSA managers just frowned at the foreign company reps and accused them flat-out of siding with "the coup-mongers even of trying to sabotage the company through this deeply seditious refusal.

Honestly, how do you work with people who think that way?

V. Now what?

One little noted upshot of this entire situation is that, contrary to popular suspicion, foreign energy companies are staying away from Venezuela in droves now. The popular misconception is that with PDVSA dismantled, the Shells and Halliburtons and BPs of the world are salivating over the prospects of a quick buck bailing the new PDVSA out. If the government seriously wants to get production back up, it's their way or the highway, right?

Not that I can see. The oil people I talk to are really leery about wading too deep into the cesspool that is the new PDVSA - not for ideological reasons, just because they're impossible to work with. Add to the sheer incompetence and arrogance the company's deepening financial troubles and the lengthening waits contractors face in trying to get paid, and you start to understand why this is a distinctly dodgy business proposition for the foreign companies. The final whammy, though, is the widespread feeling that when the Chávez regime eventually falls, foreign energy companies that threw it a lifeline will face a very uphill battle in trying to secure new contracts - they could even see some Chávez-granted contracts re-examined, a scenario that keeps foreign managers up at night. So, as far as I can see, the reports of the imminent foreign bailout of the new PDVSA are wildly exaggerated.

The truth is both more banal and far more worrying. The government has managed to crank up oil production to the 1.5 million b/d level, by the end of the year they ought to be in the neighborhood of 2.2-2.4 million b/d. It's a far cry from the 3.3 million b/d directly before the strike, particularly considering at least 500,000 b/d of prestrike capacity has been permanently lost through field mismanagement. But what's really alarming is the possibility that production won't stabilize at 2.2-2.4 million b/d but will only peak there, gradually dropping after that as insufficient investment, well-mismanagement, logistics problems and lack of maintenance start chipping away at production in a chronic way. By some people's reckoning, by the second half of 2004, we could be right back where we are now, stuck at about 1.5 million b/d.

How the government squares its books on that level of production is a mystery to me. It's really a nightmare scenario, one that economists here have never really worked through because it just never seemed like a serious possibility. Without diving too deep into the numbers you can see that a permanent revenue hit on that scale could only be worked through with mass public-sector layoffs, a debt default, or both.

Either way, the already atrocious situation of mass impoverishment I described above looks certain to worsen. The day might still come when we'll remember fondly those halcyon days when a whole 6% of Venezuelans lived above the poverty line.

February 28, 2003

So, Carlos Fernández got arrested – what’s the big problem? Listening to his speeches during the General Strike, it’s hard to argue he didn’t break some laws. In particular, when he urged people not to pay their taxes, isn’t it obvious that that’s incitement? And it’s not like Chávez went and arrested him personally: a court ordered his arrest. Isn’t that what courts are for?

It’s an argument you might find compelling, but only if you know nothing about the Venezuelan justice system. The story of Venezuela’s courts in the last four years is the story of a systematic, thorough political purge. By now, the vast majority of Venezuela’s judges have been handpicked by presidential cronies – a good number are clearly presidential cronies themselves. Take, for instance, the judge who initially heard the Fernández case. He’s a long-time chavista activist with a murder conviction on his police rap-sheet who, just a couple of months ago, was serving as defense council for one of the chavista gunmen videotaped emptying his gun into an opposition crowd back in April. He’s far from the exception.

It all started in 1999. It’s hard to believe now, but just four years ago Hugo Chávez had 80% approval ratings and the political capital to do just about anything he pleased. As part of his pledge to reinvent the state from the ground up, Chávez launched a so-called “Judicial Restructuring Committee” charged with overhauling the court system. It was a popular decision back then, and understandably so: years of old regime cronyism had left the courts riddled with political picks who took their marching orders from their respective party patrons. The courts were badly in need of a shake-up, and after years of railing against the political subordination of the judiciary, Chávez seemed like just the man for the job.

But the exercise went wrong from the start. Daunted by the prospect of having to investigate each and every judge one by one, the Judicial Restructuring Committee adopted a highly dubious expedient. They decided to just suspend all judges who had eight or more corruption complaints pending against them. Obviously, it was a quick-and-dirty shorthand. Just as obviously, it demonstrated appalling contempt for the procedural rights of the judges involved. While the move certainly cleared away many of the worst cases of judicial abuse, it doubtlessly also included all kinds of “false-positive” – honest judges who’d accumulated several spurious complaints against them and found themselves booted from the bench with no chance to defend themselves. Indeed, some 80% of Venezuelan judges had that many complaints pending against them, and it’s hard to believe that all of them really were corrupt.

The Restructuring Committee had the power to replace the suspended judges with “provisionally appointed judges.” To keep the purge from bringing the court system to a halt altogether, these provisional judges were hired after a superexpedited selection process. And that’s where the trouble started. In typical form, Chávez had named only personal supporters to the Restructuring Committee. Not surprisingly, they selected only chavistas as provisional judges. The result was a mass swap of politically motivated magistrates: out went the adecos, in went the chavistas.

But the abuse went further than that. A normal Venezuelan judge, under the old system, was terribly hard to get rid of. This created some problems – bad apples were hard to dump – but solved others – honest judges were hard to pressure. Though many judges clearly supplemented their income with bribes, and many answered faithfully to their political patrons, at least they didn’t have to worry that they’d lose their jobs if they handed down a decision that displeased their higher ups.

Provisional judges are different: they have no special labor protections. In fact, they can be removed just as quickly and easily as they were appointed by the same people who initially chose them. So by the end of 1999, not only were the vast majority of Venezuelan judges chavistas, but they were chavistas who knew their job security was totally dependent on their willingness to follow the orders handed down by their political masters.

The president and his cronies soon developed a taste for this new brand of judiciary, chuck-full as it was of defenseless provisional judges. The system made it much easier to keep judges on the straight-and-narrow. So provisional appointments – which, as the name suggests, were initially supposed to last only a few months while regular judges could be selected – became, in fact if not in law, permanent. Today, four years after the restructuring drive started, a whopping 84% of the nation’s 1380 judges are provisional appointments.

Keep this in mind the next time you read a story about a Venezuelan judge ordering an arrest of a political leader. The scrupulously neutral language of international journalism contributes to the appearance that these decisions are based on at least a minimum of democratic legality. But when it comes down to it, these judges are not any harder for Chávez to appoint or remove than his minister, and just as beholden to him.

The situation is just as bad in the Supreme Tribunal, though there the story is a bit more complex. Chávez continually says it’s absurd for people to charge him with controling the Supreme Tribunal, because the tribunal has ruled against him on a couple of high-profile cases. That, he implies, is living proof that he’s purer than pure and never set out to subjugate the court. The truth is far less flattering than that: he did try, it’s just that he was too clumsy to pull it off.

Following the approval of the new constitution in 1999, the old Supreme Court was fired en masse, and a brand new Supreme Tribunal was selected. The appointments required a two-thirds majority in parliament, which Chávez didn’t have. He had no choice but to cut a deal with some of his opponents in the National Assembly to select a new court. To their eternal shame, Acción Democrática and Proyecto Venezuela decided to play ball.

The parliamentary deal to select a new tribunal was old regime politics at its worst - a stereotypical smoky room deal. Between them, the three parties had the required 2/3rds of parliament needed for the appointments, so they more-or-less divvied up the court the way a butcher might cut up a salami. Since MVR had about 70% of the three-party-coalition’s seats, they claimed 70% of the 20-member court: 14 magistrates. AD had about 20% of the seats, so they got to pick their four magistrates. Proyecto Venezuela, as the junior partner, got to pick two. This is not speculation: I’ve heard AD leaders, who were later excorciated by the opposition for playing along on this, defend themselves publicly by saying that only by cutting a deal could they block Chávez from appointing a 100% court. “At least we have a few magistrates,” they say.

Each of the Supreme Tribunal magistrates selected in this way know precisely which party they owe their appointment to, and which party they have to take orders from. Years of angry chavista denunciations against these sorts of shenanigans were left by the wayside. It was, as one pundit memorably put it – “more of the same, but worse.”

The problem is that Chávez screwed it up. Big time. He outsourced the task of picking “his” magistrates to Luis Miquilena, who was his then right-hand man back then. He thought he could trust him. But Miquilena picked personal buddies for the job, some of whom obviously saw him, and not Chávez, as the real boss. Eventually, as Chávez’s governing style became more erratic and authoritarian, Miquilena jumped ship. And when he did, he dragged some of the Supreme Court justices along with him.

That, in essence, is why Chávez has lost some cases before the court: Miquilena has enough pull over a few of the magistrates to turn them against Chávez on selected occasions. So, in a sense, Chávez is right: he doesn’t totally control the tribunal – not anymore. But that’s hardly because either he or the magistrates underwent some sort of mystical conversion to Montesquieu’s liberal vision. The magistrates are still puppets, it’s just that one of the puppeteers switched sides.

Of course Chávez finds this situation intolerable: the very notion that an important branch of government could fall outside his control runs directly counter to the autocratic spirit that animates his whole government. So he’s had his cronies at the National Assembly hatch a plan to expand the number of magistrates from twenty to thirty, together with expedited new methods for appointing magistrates that would allow him to pick ten new, this time reliable, candidates to solidify his wavering majority in the tribunal. It’s shameless court packing. But then, shame is in short supply in Caracas these days.

The move would also solidify his control of the lower courts. Since the new constitution came into force, the Judicial Restructuring committee was wound down and responsibility for managing the nation’s courts now lies with the Supreme Tribunal, through something called the Executive Directorate of the Magistracy – DEM, after its Spanish acronym. Control of the Supreme Tribunal means control of the DEM, and through it, of all the lower courts. So packing the Supreme Tribunal allows Chávez to strengthen his control of the lower courts, and to continue to pack them with provisionally appointed cronies.

In short, the judicial system has become, like the rest of the Venezuelan state, a presidential plaything. The orders to arrest Carlos Fernández and the PDVSA strike leaders are patently, transparently political decisions, bits extracted whole from presidential speeches. These courts, which act with such frightful celerity when it comes to prosecuting the president’s opponents, slow to a glacial pace when it comes to prosecuting the president’s friends, even when those who have been videotaped shooting into crowds of unarmed civilians. To summarize the government’s judicial philosophy: if you call an opposition march you go to jail, but if you empty your gun into that march, you’re a revolutionary hero, and your lawyer is appointed judge.

February 25, 2003

Foreign philochavistas come in two flavors: the ones who don't know what the hell they're talking about and argue in broad strokes and abstract categories (those damn oligarchs are just angry because finally someone's taking on their privileges!) and the ones who do know what they're talking about - generally because they live here - and argue in good faith. While I have almost no patience for the former, I think it's important to engage the latter. Greg Wilpert, who is decidedly among the latter, writes in about my last post:

------------------

I am wondering if either you are not aware of the threats that prominent government

officials and supporters live under or if you think that such threats are not worth

mentioning. Perhaps you think they are not worth mentioning because you blame

Chavez for creating the atmosphere in which such threats exist?

If you are not aware of the threats, I suggest that you talk to some MVR diputados,

for example. Not too long ago Iris Varela's home was bombed, for example. Shortly

after the brief coup attempt, even an insignificant person such as me received

kidnapping threats via e-mail, for having written the truth about what happened on

April 11 and 12. I've intentionally been keeping a relatively low profile as a result.

The upshot is, I have no doubt that the threats against prominent pro-government

individuals are every bit as common as against anti-government individuals. The

difference perhaps is that the threats against pro-government individuals are

occasionally carried out. Perhaps you don't know about the over fifty campesino

organizers who have been murdered in the past year? There are incidents

happening all of the time, that don't even get mentioned in the government

television, perhaps to encourage the image of a happy Venezuela.

You might think that foreign correspondents should mention the threats against

anti-government politicians; I think they should mention all threats, no matter who is

being targeted - that might at least correct the image of the oh-so holy opposition

and the oh-so evil government. I personally believe that the balance of good and

evil on both sides of the conflict is more or less the same.

Best, Greg

wilpert@cantv.net

----------------

I'll be honest: I wasn't aware of a really broad-based campaign of intimidation against government supporters, though it sounds entirely likely that one exists. I've heard plenty about chavistas being harassed and intimidated when they go to the "wrong" public spaces, and I think that's awful, near-fascist, detestable, and I've argued against it both in private and in public. The overall breakdown of tolerance and civility in society is really one of the worst and most ominous aspects of the crisis.

But I have to admit I find it somewhat hard to believe that the intimidation being metted out to government supporters is anywhere near as systematic and broad as what the opposition is getting. And not because the opposition is good and the government is evil (a view I've argued against repeatedly for months,) but because in order to mount a campaign on the scale of the one opposition leaders are now subject to you really need an organization behind it - you need wiretaps and surveilance capabilities, you need money and manpower and technology and centralized decisionmaking. In other words, you need control of the state.

And this, to my mind, is the key difference, as well as the root of so much of the instability in this country: when a Chávez supporter is threatened, he can call on the state for protection. When an opposition leader is threatened, it's probably the state doing it. Or, at least, someone with the aid, or at the very least the quiescent complicity, of the state. It's the principle of equal protection under the law turned on its head.

If you want to know why Venezuela is so unstable, here's an excellent place to start. The notion that the state ought to protect all its citizens equally, regardless of their political views, seems to me like a minimal requirement for stable democratic coexistence. But President Chávez has never made a secret of his contempt for the idea. From the word go he made it clear, again and again, that he intended to govern for one part of society only, and against the other. For a long time he tried to sell the idea that he would govern for the poor and against the rich. But as anyone with open eyes here knows by now, the real dividing line is purely political: he governs in favor of those who support him acritically and unconditionally and against everyone else.

It seems entirely predictable to me that those who suddenly saw the might of the state turned against them would react with virulent rage. You threaten people, they respond. There's no mystery there. Some of those reactions have gone really way too far, and they've only made the original problem worse, yes. But the original problem hasn't changed, and it won't go away until those who have hijacked the state for their own personal purposes cease and desist.

As Teodoro Petkoff has argued many times, it's entirely specious to say that the government and the opposition are equally responsible for the crisis. Enforcing the law equally, without arbitrary distinctions, is one of the core duties of a democratic state. When a government flouts that duty as comprehensibly as this one has - when it systematically uses state money, state facilities and state power to intimidate critics, all the while giving its supporters carte blanche to do anything they want any time they want, then the minimal basis for stable democratic coexistence are compromised, and the entire edifice of a free society teeters.

And with the edifice we're in teetering, it's obviously crucial not to do anything at all to exacerbate the problem. So yes, you're right, my original post was wrong. At times like these it's very imortant to avoid mindlessly partisan postures. That's what this blog is supposed to be all about, and I was wrong not to bring up the detestable threats made against government supporters in my last post.

But I reject, strenuously, the notion that that means that we can just split the blame down the middle and leave it at that. The Venezuelan state belongs to all Venezuelans equally - all Venezuelans have a right to demand its protection regardless of their political views. It just so happens that the Venezuelan state is momentarily led by someone who vigorously disagrees with that view, someone who's launched a sort of personal crusade against the principle of equal treatment under the law, who sees of the state as a personal plaything, as a political sledgehammer he can use to pound his enemies and a petty cash box he can use to bankroll his friends. So long as we're led by someone who thinks that way, Venezuela will never be both stable and democratic again.

Pressure

It’s 3 am. You hear some strange noises outside your house. Half asleep, you crack the blinds open. You see a man, standing in the middle of the street right in front of your house. He’s looking straight at you. He has a gun in his hand. He points it up into the air. Suddenly you’re very much awake. He’s staring straight at your window. He shoots once into the air, then again, then four more times, quickly. Once he’s emptied his gun he climbs onto a motorcycle and speeds away.

That’s the worst of it, but only part of a broader pattern. Every day you get death threats on the phone. On email as well. And by fax. They know everything about you. They know where you live. They know where you work. They know your wife’s name, and your kids’. They’re following you. When you park somewhere unusual – a restaurant you don’t usually go to, say – you find notes on your windshield. “We’re following you.” This happens again and again.

Fiction? Not fiction. Just a peek into the daily life of a high-profile opposition activist in Venezuela. (I won’t reveal his identity for obvious reasons.) It’s not an isolated case.

The Chávez government has always hung its claim to respect human rights on the fact that no opposition figures have been murdered or imprisoned in Venezuela. The latter claim collapsed with Carlos Fernández’ arrest last week. The former, thankfully, still stands. But what these claims – and too much foreign reporting – gloss over is the systematic campaign of threats, intimidation and harassment government supporters have launched against all sorts of opposition figures.

The campaign is extraordinarily broad – most opposition politicians and pundits are under threat. Many journalists as well, and almost all private media owners. The threats are sustained, personal, delivered in a variety of ways. They target opposition moderates and radicals equally. Few have so far been carried out, but it’s hard to overstate the way this drip-drip-drip of intimidation poisons the political atmosphere here.

It’s important to keep this in mind when analyzing the private media’s behavior in the crisis. Media owners feel under threat. Personally. It’s not that their ideals are on the line, or their livelihoods. It’s their skin they’re worried about. Together with the high-stress nature of their jobs, the intimidation seem to be pushing some of them over the edge.

“I love my boss,” a friend of mine who works for a major media outlet tells me, “he’s a standup guy who’s taught me a lot. The problem is, he’s out of his mind.” He describes the way the mixture of the president’s threats to move against his company, together with the anonymous threats he keeps getting, have created this kind of siege mentality at the company. “He’s worked his whole life to get to the point where he can run a company like this,” my friend says “and he’s convinced that Chávez is going to take it away from him. He might be right, but the thing is that the pressure’s gotten to him. He’s just not thinking straight anymore.”

That doesn’t excuse the absence of balance in a lot of the media here, but it does help to explain it. They don’t call it psychological warfare for nothing. The unending personal threats, together with sporadic attacks against opposition newspapers and TV stations, are actually driving these people crazy. A lot of media people here have lost their ability to examine the situation in a cool, rational, detached way. The way they see it, it’s not just their livelihoods that are on the line. It’s their lives.

The threats, the torrent of well-orchestrated threats, can’t possibly be a matter of a few rogue chavistas striking out on their own to spook their political enemies. The campaign is too broad for that, too carefully run. If the government had any problem with it, it clearly could have cracked down long ago. Many here are convinced that the state security apparatus is behind it. And as the political violence escalates around the country, most are convinced it’s only a matter of time until these threats start turning into real attacks.

February 23, 2003

For a second, I worried it had been a one-off. But reading this AP story I’m more and more convinced that the foreign media’s coverage of the crisis is now shifting very significantly.

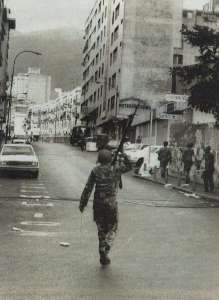

Up until a few weeks ago, incidents like last night’s shootout outside PDVSA (two blocks from where I live, incidentally!) were covered in a scrupulously agnostic way – especially by the agencies. You kept running into phrases like “a shootout ensued,” or “each side blamed the other for starting the violence,” or “after an armed confrontation, X people lay wounded” – formulations specifically designed not to place the blame on one side or the other. And last night’s shootout was, at least as I saw it, murky enough that it could, imaginably, have been the work of agents provocateurs. It’s not likely, of course: as per usual, all the circumstantial evidence suggests that it was yet another unprovoked chavista attack, but it’s not entirely impossible that some shady right-wing group could have done it to raise trouble – absent footage of known chavistas shooting, how can you be sure?

In the past, that level of doubt would have been enough to elicit the wishy-washy, non-committal language described above. It drove opposition minded Venezuelans crazy reading stuff like that, because many times the weight of evidence against the government seemed so crushing that refusing to assign blame sometimes bordered on complicity with government-sponsored violence. There were some very unfortunate episodes where chavistas were demonstrably, evidently to blame for serious attacks - more than a couple of incidents were even photographed and videotaped and really left no room for doubt - and yet the foreign papers were just not willing to come out and say it clearly.

That’s one problem we don’t have in the post-Fernández-arrest era. The AP write-up is astonishingly unambiguous in assigning blame over last night’s shootout:

"Gunmen loyal to Chavez ambushed a group of policemen overnight, killing one officer and wounding five others, said Miguel Pinto, chief of the police motorcycle brigade. The officers were attacked Saturday night as they returned from the funeral for a slain colleague and passed near the headquarters of the state oil monopoly, which has been staked out by Chavez supporters since December. After a series of attacks on Caracas police by pro-Chavez gunmen, Police Chief Henry Vivas ordered officers to avoid oil company headquarters. But the funeral home is located nearby.

'We never thought it would come to this,' Pinto said.

Chavez's government has seized thousands of weapons from city police on the pretext that Vivas has lost control of the 9,000-member department. Critics allege Chavez is disarming police while secretly arming pro-government radicals."

Now, the journalists reading this know how the sausage is made. This is not the way you write a story if you mean to leave any doubt in your readers' minds about who's responsible for the killing. It’s a gutsy way to write, really - and refreshing to see in the typically bland AP. It just goes to bolster my theory that Chávez screwed up big time with Carlos Fernández – the speed with which the benefit of the doubt has vanished is amazing. He can expect to get raked over the coals abroad for every little slip up now. Once the media start treating you this way, it’s a matter of time until you end up with full-on pariah status. This shift has been a long time in the making. Now, it’s happening.

February 21, 2003

There’s one positive side to this whole Carlos Fernández incarceration hubbub: the foreign press is finally taking the gloves off. After months of not quite knowing how to deal with the crisis, of not being entirely sure whether to treat Chávez like a normal democratic president or an autocrat, the Fernández episode seems to have tipped the scales. It’s the Mugabization of Hugo Chávez in the court of world public opinion. It’s still far from complete, but now it’s definitely on the way.

Consider this remarkable story by Scott Wilson in the Washington Post. I’ve been friends with Scott for a long time and consider him one of the best journalists around – he’s not the kind of observer you can snow under with propaganda, much less recruit him to peddle yours. For a long time, I’ve had the feeling he understands, at a gut level, how dangerous Chávez is. But – and this is really difficult for opposition-minded Venezuelans to understand - Scott doesn’t draw a paycheck to tell the world how his gut is feeling. As a reporter, his code of ethics dictates that he can’t go any further than the facts allow. And for a long time, with Chávez going to lengths to maintain a fiction of democratic legality, the facts remained just too murky to report in Mugabian terms.

But in jailing an important opposition leader, Chávez crossed a kind of red-line, transgressing the first commandment of third world leaders hoping for sympathetic treatment in the foreign papers – thou shalt not indulge in behavior stereotypical of a dictator. And now he’s paying the price. His treatment in the Post is absolutely brutal. I’ve never seen the government take it this hard in a reputable foreign news story before. I think a lot of foreign journalists were, in a sense, waiting for a big stink-up to pounce – and now the stink-up is here, the government's heavy autocratic character is in plain for all to see, and the pouncing has started.

Good.

Reuter's is just as harsh as the Post - they played that papaya quote for all its worth - and AP is just scathing – I can’t think of a lead anywhere near as biting as this one in any AP story I've ever read out of Venezuela. In, the Wall Street Journal Marc Lifsher writes of “death-squad-style killings.” The NYT had been behind the curve on this one, but they put out a quite strong editorial condemning the arrest, and they’re flying in David González tonight, and while I only know him superficially, he’s a fantastically talented reporter and can be expected to write some good stuff.

Is it the Full Mugabe yet? Not quite. But the treatment Chávez is getting now is far, far closer to it. My fear is that he’ll use the international media blackout that will come with the start of the war on Iraq for cover – people will be very nervous here the day the war starts. Specifically, it’s easy to foresee that he’ll move against the private TV stations within minutes of the start of the war. Under normal circumstances – and the stories of the last few days bear this out – he’d be pilloried abroad for a stunt like that. But with the green lights streaking over the skies of Baghdad on CNN, who can tell?

February 20, 2003

The price of dissent

What do you call a political leader jailed for his political views? A political prisoner, right?

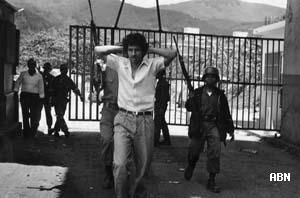

Just wanted to settle that up front – President Chávez’s endlessly repeated claim that there are no political prisoners in this country is now dead. Last night, the government “arrested” Carlos Fernández, one of the most visible opposition leaders, in a secret police operation that looked more like a kidnapping – a dozen heavily armed men suddenly jumped on him and commandeered his car, as he was leaving a restaurant. There was no district attorney present (as required by Venezuelan law), these guys showed no arrest warrant, they are keeping him incommunicado and they won’t even confirm his whereabouts. So where, exactly, is the borderline between an arrest and a state-sponsored kidnapping?

Carlos Fernández is far from my favorite opposition leader – he’s crass, often radical without a purpose, he’s a terrible public speaker and he played a major role in leading the opposition up the garden path known as the General Strike – a fantastically dumb adventure that did nothing but consolidate Chávez in power. Yet seeing him arrested in this way seems to back up everything he always said about the government: that they haven’t the slightest clue what democracy is all about, that they’ll stop at nothing to consolidate themselves in power, and that they treat the constitution the way your cat treats his litter box.

Watch for the foreign lefties to start justifying his arrest on the grounds that, christ, he’s the leader of the business association, he must be some sort of evil blood-sucking plutocrat, and it’s ok if they go to jail, right? Don’t laugh, it’s the precise corollary to Naomi Klein’s argument on the press in The Guardian the other day.

But beyond that, Fernández is a genuine self-made man, a postwar immigrant from Spain who was penniless on arrival, built up a trucking firm from a single truck into a fairly large company, and rose through the ranks to preside the major business federation here, Fedecamaras. It’s the Venezuelan dream, the dream of tolerance and social mobility Chávez can’t stand because it lays bare the bankruptcy of his vision of Venezuela as an ossified, near-colonial society.

For decades, Venezuela had been well past the political cultural of responding to dissent with jail. Under Chávez, we seem to be regressing.

February 18, 2003

NO CLUE

We interrupt this essay series to attack Naomi Klein, of NO LOGO fame, who in a remarkably ill-considered piece in The Guardian supports the Contents Law and obliquely calls for Venezuela’s private broadcasters to be shut down. I’m amazed at the way parts of the antiglobaloization crowd have abandoned what I’d always thought of as baseline liberal values, like freedom of the press.

The facts in her essay are – and as a Venezuelan journalist, I’m ashamed to admit it – mostly right, but the conclusions she draws from them strike me as demential. Her lionization of Andrés Izarra, that insufferably self-pitying chavista martyr, is enough to work up anyone who knows anything about him into a fit of rage. More importantly, though, Klein glosses over a series of key fact in her piece, like the president’s outrageous and repeated attacks on the media, the systematic harassment of Venezuelan journalists, the threats too many of my colleagues keep getting simply for doing their jobs. Reading it, you’d never known about the government’s campaign of constant incitement to violence against anyone who dares question Chávez in the press. If you didn’t know anything else about the situation here – which is doubtlessly the case for most of Klein’s readers in The Guardian – you’d think Venezuela’s media moguls just sort of woke up one day and said “golly gee, it’s so much harder to exploit the working class with this guy in power, let’s topple him!”

It’s shameful.

February 14, 2003

The petrostate that was and the petrostate that is

The Petrostate that was and the Petrostate that is:

I: The Accion Democratica Model

Back in 1996, I did some field work in Cabimas, a dusty little oil city in on the eastern shore of Lake Maracaibo, for my thesis on the Venezuelan labor movement. One day, I saw a bunch of guys playing basketball at a municipal court and thought I'd hang out with them for a while - not that I'm any good at basketball, but I thought they might offer a different perspective.

Later, when I told my labor movement buddies what I'd been up to, they were horrified. "What!? You were hanging out with those adeco basketball players? Oh Jesus, did you give them any information?!"

I was shocked. Adeco basketball players? I'd often read about how deeply political parties had penetrated the fiber of everyday life in Venezuela, but the notion that even the guys shooting hoops down the street had a party affiliation struck me as deeply weird.

I was shocked. Adeco basketball players? I'd often read about how deeply political parties had penetrated the fiber of everyday life in Venezuela, but the notion that even the guys shooting hoops down the street had a party affiliation struck me as deeply weird.Undaunted, I went back and asked them about it.

"So, you guys are from AD?"

They kind of smiled awkwardly and one of them said, "well, we needed a court and..."

He went on to tell me the story about how they'd always wanted a proper court to play on, and they'd never had enough money for shoes, balls, uniforms, coaching...all the stuff you need to join a youth league. The mayor of Cabimas was an Accion Democratica politician and one of the guys mentioned his uncle was an AD member, so they asked him for help.

The uncle pointed them to their neighborhood AD party organizer. They went and asked him if the city would built them a basketball court. The organizer said he would be happy to press their case with the mayor, but told them the mayor would be, cough-cough, much more likely to agree to it if they'd sign up to become party members.

The bargain was simple - a chunk of the municipal recreation budget in return for becoming AD members and helping out with election campaigns and get-out-the-vote drives. That didn't strike the guys as such a bad deal. So they signed up, and after a year or so they'd gotten their court and some gear...with the slight inconvenience that the whole town started to think of them as "those adeco basketball players."

And there you have it: at its core, that is the Venezuelan petrostate.

The petrostate is a mechanism that turns oil money into political power - or, more precisely, control of the state’s oil money into control of the state - in a self-perpetuating cycle.

The way you do that is by building a huge patronage network. Tammany Hall politics on a national basis.

Those kids shooting hoops in Cabimas had never heard of Terry Lynn Karl, but they instinctively grasped how the system worked. And so did their neighborhood party organizer: he was able to use his influence over a tiny share of the state’s oil revenue – just enough to get a basketball court built - to fund a miniature local patronage network. His clients - the guys - would return the favor on election day, not due to any sort of ideological affinity, but simply to keep their access to his influence over funds. And he would use his influence over them - his ability to mobilize them for political purposes - to bolster his position as client to the next patron up the line: the mayor.

That basic, pyramidal structure was replicated all throughout the country, in every imaginable sphere of life, from multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects to things as petty as a neighborhood basketball court.