Katy says:

Katy says: Influential British magazine

The Economist (registration required) has a

very interesting article on national oil companies and how they have often served as cash cows for governments instead of behaving like profit-maximizing companies. Not surprisingly, the article starts off with tales of PDVSA, past and present. An excerpt:

...

"EXXON MOBIL is the world's most valuable listed company, with a market capitalisation of $412 billion. But if you compare oil companies by how much they have left in the ground, the American giant ranks a lowly fourteenth. All 13 of the oil firms that outshadow it are national oil companies (NOCs): partially or wholly state-owned firms through which governments retain the profits from oil production. Because these national champions control as much as 90% of the world's oil and gas, they can do far more than the likes of Exxon to assuage the current worries about supply and to influence the accompanying record prices. But like most state-owned firms, they are prone to over-staffing, underinvestment, political interference and corruption.

Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), one of the biggest (see chart on the next page), provides a cautionary tale of how bad they can be. Venezuela has exported oil since the 16th century, when the mother of the Hapsburg emperor, Charles V, had some shipped to Spain to treat his crippling gout. Big multinationals, such as Royal Dutch Shell, set up shop in Venezuela almost a century ago. By the 1930s the country was the world's second-biggest oil producer. Today it remains one of the main sources of American oil imports. There is also huge potential to expand production: if you include its near-endless supply of treacly "ultra-heavy" oil, Venezuela has the world's biggest reserves.

Like many developing countries, Venezuela nationalised its oil industry in the 1970s. But its politicians were mindful of the extravagant mess that Pemex, Latin America 's biggest NOC at the time, had made of Mexico's oilfields since the 1930s. So the Venezuelans devised a structure to minimise the disruption. Former foreign concessions became free-standing divisions of PDVSA, with many of their existing managers left in place.

From these sensible beginnings, PDVSA developed a reputation for professionalism and competence, matched by few other NOCs. The company was thought to be relatively free from the corruption and cronyism that had spread through Venezuela, fuelled by oil wealth. It was certainly efficient, producing as much oil as Pemex did with a third of the staff.

In the 1990s the Venezuelan oil company embarked on a scheme to raise output to 6.5m barrels per day (b/d). This would be done by increasing its own production and farming out marginal fields to foreign firms. The idea, says Luis Giusti, who ran PDVSA from 1994 to 1999, was to make use of multinationals' technology and capital without surrendering the most lucrative opportunities to them.

By 1998 some 36 foreign firms had set up shop and were rapidly expanding their output. PDVSA, meanwhile, had already reached 2.9m b/d and was seeking the government's blessing to invest more to increase its production capacity. But royalties were falling along with the oil price. With an election looming, the government slashed the company's investment budget instead. Output promptly started to fall and has never recovered.

Partly because of geology and partly because of their age, Venezuela 's fields require a lot of maintenance. The oil they produce is more viscous and acidic than the norm, and so harder to handle. Less than a tenth of the fields simply spout oil thanks to the natural pressure of the reservoir. Keeping the remainder flowing requires constant injections of water or gas. Even so, their output declines at roughly twice the pace of oilfields in the North Sea. Venezuela has to add 400,000 b/d of new annual production capacity just to keep output stable, according to Mazhar al-Shereidah, an academic.

That is even more expensive than it sounds, because each well produces only a small amount: perhaps 180 b/d, compared with as much as 7,000 b/d from some Persian Gulf wells. It takes Venezuela ten times more wells than Saudi Arabia to produce a third of the oil. No wonder that at the height of its expansion in 1997, PDVSA was investing $5.4 billion, according to Wood Mackenzie, a consultancy.

But when President Hugo Chávez came to power in 1999, he started squeezing even more money out of the firm. By 2000 investment had fallen to $2.5 billion. Mr Chávez accused PDVSA of hiding its profits from the government through deceptive accounting. He also questioned the firm's expansion plans and overseas acquisitions. Above all, he decried its relative autonomy and appointed a number of hostile bosses to impose his authority.

PDVSA's management, naturally, resented this. They joined a general strike in December 2002, along with half of the firm's 40,000 employees. Most of the skilled staff, including engineers and technicians, stopped work for two months. Since—like patients in intensive care—many of PDVSA's wells require constant monitoring and treatment, says Mr al-Shereidah, the strike killed lots of them. Analysts estimated that Venezuela lost as much as 400,000 b/d of production capacity for ever, not to mention billions of dollars in revenue.

But the worst was still to come. Mr Chávez denounced the strikers as saboteurs and sacked them all. The toll was highest among skilled workers: two-thirds of managers and technical staff went. At a stroke, PDVSA lost almost all of its most experienced and best-qualified employees, with an irreplaceable understanding of the idiosyncrasies of its wells and fields.

Critics say that the government restaffed the firm with incompetent cronies and placemen. Contractors whisper that it is having trouble spending even its reduced investment budget. Bids take months longer than necessary to complete, one contractor complains, because the procurement staff cannot get their technical specifications straight. Others point to an increase in fatal accidents and fires at PDVSA's refineries as proof that its workers are no longer up to snuff.

Staffing has certainly become more political. Mr Chávez's cousin, Asdrubal, runs the firm's shipping arm. The president's brother, Adan, helps to co-ordinate the company's subsidised oil sales around the Caribbean as ambassador to Cuba . Those who signed a petition advocating a recall election for Mr Chávez complain that they cannot get jobs at PDVSA or its contractors.

Politics has begun to intrude into the firm's strategy, too. Mr Chávez wants PDVSA to do less business in the United States and more in Latin America. In the name of regional integration, he is pushing for an expensive natural-gas pipeline from Venezuela to Brazil , which would "bring gas that does not exist to markets that do not exist", in Mr Giusti's view. In theory, the hugoducto, as the pipeline is sarcastically known, will be a money-making venture, but Mr Chávez has also dragooned the company into all manner of charitable works. He insists that the firm spend a tenth of its investment budget on social programmes, and has pledged its help, in the form both of cheap oil and technological assistance, to allies from Argentina to the Bahamas.

Clearly, Venezuela's oil company no longer operates at arm's length from the government. Its head, Rafael Ramírez, is also the Minister of Energy and Oil. "The president tells PDVSA to commit suicide, and he says, 'Yes sir!'" gripes Elie Habalian, a former Venezuelan representative at OPEC, with a mock salute.

The company is also becoming more secretive. It has de-registered its refining subsidiary, Citgo, at America's Securities and Exchange Commission, and so no longer files any public reports to the organisation. In Venezuela, the Ministry of Energy and Oil has only just released the 2003 edition of its annual statistical compendium on the company's performance. Its finances are certainly getting murkier: it now transfers much of its earnings directly to a development fund controlled by Mr Chávez, rather than sending them all to the central bank as it used to.

Despite these worrying trends, the government claims that PDVSA has fully recovered from the strike and sackings, and is now producing more than it did beforehand. Officially, it is still planning to raise output to almost 4m b/d by 2012. But observers scoff at such notions. The company can no longer maintain its own fields, let alone complete the many new projects it is pursuing, says Diego González, who used to work for its gas division. Wood Mackenzie estimates that output slumped to less than 1.2m b/d in 2003. It subsequently recovered a bit, to 1.6m b/d, but is now falling again.

These failings have not stopped Mr Chávez from forcing most foreign oil firms in Venezuela to go into partnership with its national champion. It is now running the resulting joint ventures—presumably no better than it runs its original fields. Other countries go further: Saudi Aramco, for one, has a monopoly on oil production in Saudi Arabia. PFCEnergy, a consultancy, calculates that 77% of the world's oil and gas is found in countries whose production is controlled by state-owned oil firms and their partners."

...

Later on, the article says:

...

"

Happily, not all NOCs are as badly run as PDVSA. But their problems are similar, if not as severe. Many suffer from government meddling of one sort or another. Legal requirements to hire a certain number of locals have left the state firms of several Persian Gulf emirates hopelessly over-staffed. Russia uses its NOCs, Gazprom and Rosneft, as instruments of foreign policy. The governments of China and India, among others, oblige their state firms to sell petrol below the international price at the pump, even though they have to buy much of it on the open market. Bolivia, meanwhile, cannot decide whether it wants an NOC at all. It has opened its oil industry to foreign investment and then nationalised it no fewer than three times."

...

The article is a must-read. It makes many of the same points Terry Karl made in

The Paradox of Plenty, her legendary book on the many ills of petro-states. It is also a point reaffirmed by Quico in his post on

Petrostates. Still, it is nice to see these important issues being raised yet again by a regarded publication such as

The Economist that appeals to such a wide audience.

Let's wait and see how the chavista propaganda machine try spin its way out of this mauling.

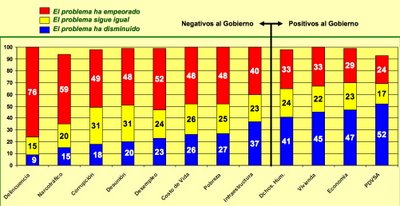

[Click to expand.

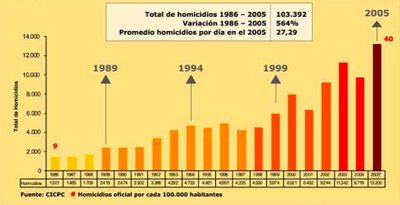

[Click to expand. Venezuela's Murder Rate: Click here to expand

Venezuela's Murder Rate: Click here to expand