Juan Cristóbal says:

Juan Cristóbal says: -

My friend Roger used to be my mole in the government. A committed

escuálido working undercover deep inside chavista bureaucracy, he somehow managed to tolerate the mind-numbing paper-pushing and the constant backstabbing from colleagues and underlings alike, to say nothing of the forced participation in chavista rallies.

But over the last year, Roger also got a crash course on the true nature of chavista bureaucrats, people for whom corruption, inefficiency and amateur Machiavelianism are the norm.

Unwilling to play along, Roger got fired last month.

Roger is a classic example of the underpaid overachiever. After getting his law degree in Venezuela, he went to Switzerland on a scholarship and got his doctorate. There, he specialized in an obscure area of international law that, luckily, is also incredibly relevant for Venezuela.

As it happens, he never got around to signing the recall petition against Chávez so he's not in the Tascón or Maisanta Lists. Long story short, that meant he could get a job in

the government institute that handles the exact area of his expertise, doing the things he was actually trained to do. His legal knowledge and his ability in three languages became important assets and helped him stand out in the many international conferences he went to.

"Deep inside," he fesses up, "I kidded myself with the idea that I was giving something back."

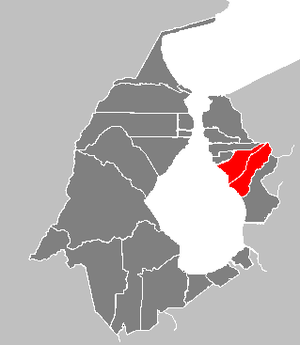

These days, Roger whiles away his afternoons in his apartment in La Urbina, where he lives alone with his computers, his books and his view of Petare. He hasn't worked in weeks and is living hand to mouth.

And yet, he's at peace with himself. When I ask him the story behind his firing, he is almost wistful, disconcertingly zen about the whole thing.

He says the beginning of the end of his public service career came when his institute got a new chairman a few months back, his fourth new boss in as many years.

"This last guy took part in the 4-F military coup," he says. "The fact that he was dispatched to a relatively obscure technical outpost of chavista bureaucracy as compensation speaks volumes about his performance that day."

From day one, the chairman decided he didn't like Roger one bit. His language skills, the depth of his knowledge and his personal demeanor all rubbed him the wrong way.

"The problem is that you don't fit in with the culture," one of his assistants told Roger.

How so? he asked.

"Well," she said, "you don't socialize, all you do is come in, do your work and you're out. You don't joke around with everyone, you don't seem to like us. You're very Swiss that way."

Roger spent six months trying to get a meeting with the chairman, trying to get him to read his reports. In six months, he got nothing.

Well, not quite. He did get a lot of work on weekends.

In the months leading up to last November's State and Local Elections, Roger got dragged to election meeting after meeting and rally after rally. On several occasions, he was part of special PSUV cleanup operations in the squares and plazas of Caracas.

The demands on public employees before elections became difficult to put up with. Right before February's referendum, Roger was forced to sell BsF. 1,000 worth of raffle tickets to raise funds for the PSUV's campaign. Needless to say, Roger couldn't think of anyone who would want to buy his tickets, so he had to pay for them out of pocket.

"Did you at least win anything in the raffle?" I ask, all hopeful.

Hardly. As it happens, the raffle tickets were fake. The real ones were supposed to have a serial number and a bank account where the funds should be deposited.

Roger's had none of that. The chavistas in the office forcing him to sell them had given him

tickets chimbos.Under the new chairman, office life soon took a turn to the bizarre. One Saturday, the guy decided to stage his own little backyard version of "Aló, Presidente." He made all senior and middle management go to work and sit in a conference room, from 8 to 4, hearing him talk about whatever was on his mind.

His secretary, who is actually his mistress as well as the niece of one of Chávez's ministers, was in charge of filming. During the proceedings, she would point the camera and focus on managers who looked bored, were staring at the ceiling or sending text messages. The chairman would review the tape and reprimand managers who weren't devoting 100% of their attention to the boss.

The level of paranoid control just kept getting ratcheted up. During regular weekdays, all managers had to text message the chairman every time they left the office. The Saturday seances soon became compulsory, with attendance strictly enforced. One Saturday, Roger arrived an hour late and was asked to provide the reasons why he was late ... in writing. Needless to say, he had to suck it up and say it wouldn't happen again, just like ministers do on

Aló, Presidente when the big guy humiliates them.

In the Chávez administration, imitation has gone from highest form of flattery to outright obsession.

One of the problems Roger faced was the lack of personnel. Even though he was technically a manager, he never got an assistant or a secretary, so all his department's work fell on his lap.

Conveniently, the 28-year old daughter of his longtime nanny was looking for a job. Thanks to her mother's hard work, Judith had received a technical degree and had just arrived from a stint living in London.

Since she was bilingual, qualified and available, Roger pushed hard to hire her as his secretary. After many interviews and even after sucking up to all the right people, he was told they couldn't hire her because she was in the Tascón List. Roger was forced to apologize, saying he didn't know and simply forgot to check. Had he known, he said, he never would have insisted.

Judith is still unemployed.

In the weeks leading up to his firing, Roger got assigned an "advisor." Edgar, a PSUV apparatchik, had a simple job: sit across from Roger's desk every day and make his life miserable. While Roger tried to focus on his work, Edgar would talk on his cell phone non-stop, only pausing to bark at Roger demanding he finish his reports so he could take them up to the chairman and pass them off as his own. Roger later found out Edgar was making twice as much as he was.

The day Roger was fired - by Edgar, of all people - he received several anonymous text messages. "The institute is rejoicing," one read, "so much for your fancy degrees and your languages. Go eat shit, you show-off."

I ask him what the source of so much animosity is. It turns out that, with Roger being in charge of international legal analysis, his office was responsible for most of the trips abroad. The decision of who to send in each delegation frequently fell on Roger, and he obviously preferred sending the few qualified people available.

This, of course, did not sit well with the rest of the sprawling bureaucracy. Thanks to Misión Cadivi, going to one of these international trips was a quick and easy way of landing some hard currency in the form of juicy

per diems, which everyone simply kept and later sold in the black market. Plus, you could have a good time abroad too. Roger recalls one particular conference in South Africa where the head of the delegation simply did not show up for the meetings, preferring to go on safari with his mistress instead.

I ask Roger about the laws Chávez has passed, banning the firing of employees. He tells me he really isn't an employee. Since the institute is relatively new, they have not established the positions and their role in the larger picture of the government's bureaucracy.

This is on purpose. Done this way, everyone is under contract and can be fired at any time. Plus, this allows the institute bigwigs to bypass regular budget laws and just hire all their friends, giving them cushy jobs as payback for political favors.

These days, Roger is reinvigorated. Leaving all those negative vibes behind, he says, he's starting to enjoy life again. He'd gotten to the point where he was spending most of his energy thinking up ways to outscheme the schemers out to get him. Now, he says, he's glad to have the time off, getting in touch with his friends again, teaching.

"It's funny," he says, "but the more I think about it, the more it makes sense. Of course the government doesn't work. My former boss is an ex-con, a convicted felon, an anonymous military man whose sole claim to fame was to break the very oath he had taken and violate the democracy he had sworn to defend. Of course they don't believe in building institutions! Their only talent, the thing they spent years planning, is how to do away with them. What was I supposed to expect - decency?"

My sense is that Roger is going to be OK. He may have lost his job, and may well end up having to live abroad, but he is well on his way to getting his life back.

Juan Cristóbal says: In the last few months, the government has ratcheted up the pressure against the only opposition TV station left in Venezuela, the small all-news outlet Globovisión. Chavismo is going all out, charging the company and its executives with everything from tax evasion to psychological war to environmental crimes (on account of a few head of stuffed moose hanging in the walls of the station's owner), not to mention a relentless propaganda campaign on state media against the station.

Juan Cristóbal says: In the last few months, the government has ratcheted up the pressure against the only opposition TV station left in Venezuela, the small all-news outlet Globovisión. Chavismo is going all out, charging the company and its executives with everything from tax evasion to psychological war to environmental crimes (on account of a few head of stuffed moose hanging in the walls of the station's owner), not to mention a relentless propaganda campaign on state media against the station.