Well, I've just finished my week-long

WTO Negotiation Simulation (so be prepared to be bored silly with the details.)

I have to say it was fantastic. The session was run by real-world trade negotiators, which kept it sophisticated and realistic. The simulation chairman, who

represents South Africa in the real talks, pushed us hard to reach an agreement - which, at the cost of some realism, we did. None of us, however, was under any illusion that our simulated agreement could work in the real world. Just the opposite: as the simulation progressed, it became clear to all of us that the "zone of possible agreement" could only be reached if all the delegations gave up not on this or that peripheral point, but really on their main negotiating goals. In that sense, the exercise was valuable mainly in giving us a much more detailed, nuanced understanding of where the tangle of deadlocks really lie and why the multiple impasses have been so unmanageable.

For the few of you who really care, and at the cost of some heavy-duty oversimplification, it goes something like this:

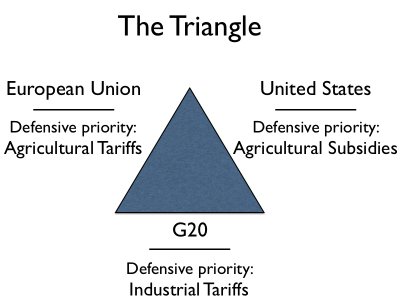

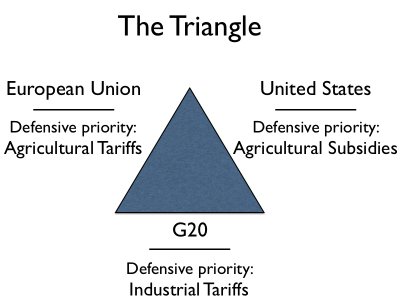

At the center of the Doha Round there's a three-way deadlock between the three main players on the three main topics up for negotiation - a fundamental impasse we came to call "the triangle." The three players are the European Union, the United States, and the G20 group of relatively advanced developing countries - which includes Brazil, India, South Africa, Thailand, Argentina and China (and, incidentally, Venezuela as well.) The basic problem now is that these three have to agree on three very tough topics: agricultural tariffs, agricultural subsidies, and industrial tariffs.

Each of the three big players has two offensive interests (where they try to get the other two to liberalize) and one defensive priority (where they want to avoid having to liberalize themselves.) The kicker, of course, is that each player's defensive priority is also the other two players' offensive priority. Visually, it's like this:

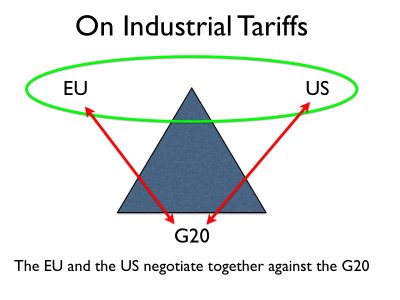

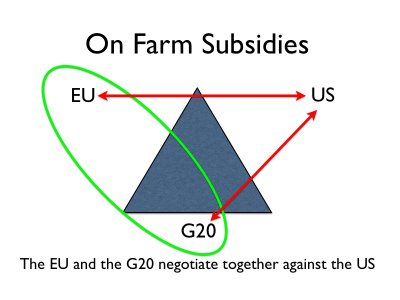

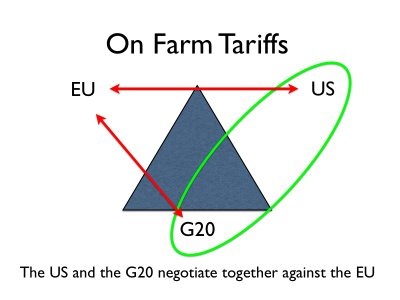

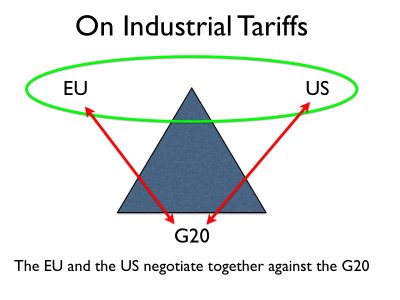

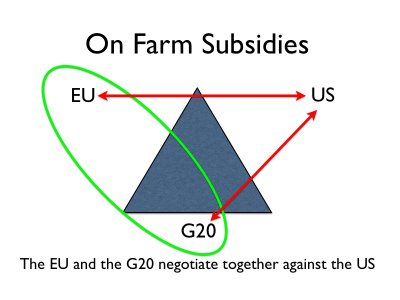

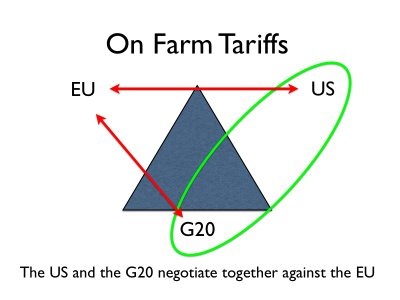

Of course, this is a highly schematic way to set it out, and leaves out a lot of contradictory detail - the lavishly tariff-coddled US sugar industry could only smirk at all this. Still, as a first approximation to the deadlock, the triangle is a pretty good tool. It allows you to appreciate the neat symmetry in the three-way deadlock. Each issue pits two of the blocks against the third, in a kind of round-robin of futile alliances:

Why does it end up breaking down like this?

Well, take the Europeans first. The EU negotiates defensively on agricultural tariffs because EU farmers are protected chiefly by high tariff walls, and many would find it very hard to survive without them. So the EU's first negotiating priority is to avoid having to cut them seriously. Though European farmers also benefit from high subsidies, the EU's Common Agricultural Policy has been extensively reformed in the last two years to ensure those subsidies are allowed under WTO rules - so the EU has an interest in seeing other partners, especially the US, reform and lower their own farm subsidies as well. At the same time, European industrialists are strongly interested in selling their manufactured goods all over the world, so their foremost offensive priority is to get lower industrial tariffs in the US and G20 markets.

The United States, on the other hand, negotiates defensively on agricultural subsidies, and offensively on agricultural and industrial tariffs. US farmers are protected mostly by high subsidies, which have not been reformed to conform with WTO rules. So the US Trade Representative's major red-lines concern avoiding deep cuts in farm subsidies. Although US farmers also benefit from high tariff walls, on the whole they are not as high as Europe's. US farmers operate on a larger scale than European farmers and have higher productivity, so they could survive and thrive with lower tariffs if the EU would also drop theirs. And just like the Europeans, US industrialists are strongly interested in selling their manufactured goods all over the world, so negotiating for lower industrial tariffs in the EU and G20 markets is an offensive priority.

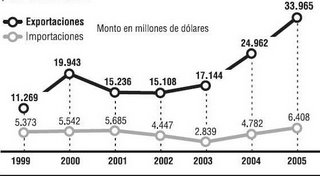

Though there's a lot of heterogeneity in the G20 - hell, Egypt is a G20 country! - on the whole G20 farmers enjoy few subsidies and strong comparative advantages in agriculture: if world food markets were not so distorted, the G20 would "feed the world." Their negotiators therefore push to secure deep cuts in farm tariffs and subsidies in the rest of the world. Though the G20 is officially an agriculture-only club, and therefore doesn't have an official position on industrial tariffs, everybody knows that many G20 industrialists - particularly in Brazil, Argentina, South Africa and India - are not competitive enough to survive if industrial tariffs are cut substantially, so most G20 countries negotiate against having to lower their own industrial tariffs. (This, obviously, doesn't apply to China.)

The tangle of irreconcilable differences arising from the triangle is frightful. The European Union will only agree to cut its own farm tariffs if the US cuts its farm subsidies and the G20 sharply lowers its industrial tariffs, but both the US and the G20 find these proposals unacceptable. The US will only cut its own farm subsidies if the EU sharply lowers its farm tariffs and the G20 quickly drops its industrial tariffs, but both the EU and the G20 find those proposals unacceptable. And the G20 - well, if they had a position on industrial tariffs, which they don't, it would be that they would only drop their own industrial tariffs if the EU and the US will cross their own "red-lines" on farm tariffs and subsidies respectively, which neither is willing to do. Put together, the three sets of red-lines generate an insurmountable deadlock.

The Obvious SolutionNow, you don't have to be a negotiations expert to notice a fairly straightforward potential solution to all this: for all three players to make deep concessions on their own defensive priorities at the same time. That way, each would give on their one defensive issue, but get on their two offensive priorities. This, in fact, is the solution we reached in the simulation exercise. And, of course, the real negotiators in Geneva are not stupid: they realized long ago that if there is going to be a deal, it will have to be something along those lines.

What's really interesting, though, is that this kind of common-sense solution just won't fly: they've been trying to hammer out a deal along those lines for 5 years now, and there seems to be no way to square the triangle.

The reason, I think, is that trade negotiators consistently prioritize their defensive interests over their offensive interests. As one of the speakers quipped to us this week, "no WTO negotiator has ever lost his job for saying 'no', but plenty have lost their jobs for saying 'yes.'" And with good reason: the costs you incur from caving on your defensive interests are real, rapid, and tangible. But the benefits from getting a concession on your offensive interests are uncertain, evanescent, nebulous...if they come, they rarely come right away.

If you take away a European farmer's tariff protection he notices, immediately, because the price he gets for his product falls. If the EU gets Brazil to agree to lower its own industrial tariffs, on the other hand, any given European exporter may or may not get any of the benefits. He may find that those lower tariffs just allow their US or Chinese competitors to make off with the extra market share. They may find that Brazilians don't like their brands as much as expected. The boat carrying their product could sink. Any number of problems could crop up that overwhelm the benefits, to him, of the agreed cuts in Brazilian tariffs. So getting that lower tariff in Brazil is a gain for the EU, but it's a gain in a strangely nebulous, highly uncertain, off-in-the-future kind of way.

Defensive biasFor these reasons, producers are generally much more interested in lobbying to protect their defensive interests than they are in lobbying to further their offensive interests. Defense has a built-in advantage in the Doha Round, and the primacy of defensive interests in the triangle seems to be the main reason for the impasse.

This is a problem in all three trade blocks, but it's not a symmetrically distributed one: it's much more of a problem in Europe than elsewhere. European politicians are petrified of the reaction they could get from their farmers if they cut farm tariffs deeply, no matter what concessions they get elsewhere. The problem is compounded by the low level of engagement by the EU's offensive interests: the industrial lobby, whose support European negotiators badly need, sees little to gain from further tariff cuts abroad, largely because industrial tariffs are already, generally, quite low worldwide.

Interestingly, the US that has the most flexible position in the round, because their defensive priority is the easiest to fudge: the way the negotiation has developed is that only the most "trade distorting" farm subsidies would be sharply cut, while subsidy programs that are designed to be "minimally trade distorting" are still allowed. In theory, the US could agree to sharply lower its "bad" subsidies and then just shift the money over to "good" subsidies, leaving gringo farmers as well-off as they were before. All they would have to do is reform their farm policies. Indeed, that's precisely what the EU did with its own Common Agricultural Policy in the last few years. It's not politically easy, but it's not the end of the world either. For that reason, both in my simulation and in the real negotiations, the US has had a more moderate position than the EU and the G20. "Caving", for the US, would mean reforming their farm subsidies, not giving them up outright. So the US side of the Triangular Deadlock looks to be the most manageable of the three.

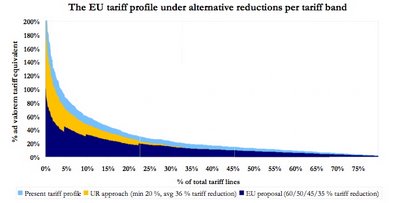

The G20, meanwhile, has the most offense-minded position of the three: the benefits from liberalization to their agricultural exporters are quite well established and visible to their farm lobbies. The G20's problem is a bit different: their defensive priority is industrial tariffs, but those are already very low for most products in almost all countries. In order for a G20 concession on industrial tariffs to be meaningful for the EU and the US, the G20 countries would need to make extremely aggressive cuts on the tariff lines they still have. The EU, for instance, is calling for a deal that radically cuts all tariffs and allows no single tariff to remain above 15%. This is an extremely aggressive stance, and one several G20 countries simply couldn't stomach. Kirchner, in particular, would never in a million years agree to a cut on that scale. Though the G20 does not have a single position outside of agriculture, the working guess is that the group wouldn't agree to cut its highest tariffs below 40% or so. (Needless to say, the second G20 countries float that sort of position, the EU loses all interest in serious agricultural tariff cuts.) My point here is simply that the gaps we're looking at are so wide that any question of somehow "splitting the difference" is entirely unrealistic.

Esperando en la bajadita...Then again, this central deadlock has been clear for some time. The more valuable part of the simulation (for me anyway) was the realization that even if you somehow managed to untangle the triangular deadlock, the negotiations could still well fail. That's because a number of other deadlocks continue to lurk in the shadows of the negotiations, concealed only by the fact that the three-way big-player deadlock is even worse.

These other deadlocks are far from negligible, though. For one thing, the G10 countries (Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, Norway and Co.) are even more protectionist in agriculture than the EU and the US, so even a proposal agreeable to the three big players may not be acceptable to the G10. For another, the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group demands a separate, quicker, deeper deal to liberalize cotton (a main export product for some of their members) which sets them on a collision course with perhaps the most powerful agricultural lobby in the US. The ACP countries also demand compensation for the loss of their preference margins, which is implicit in any tariff-cutting proposal. And the G33, (yet another group, this time of larger, poorer developing countries, and led by Indonesia) has demanded two large loopholes against having to cut many of their own farm tariffs that is acceptable neither to the US nor to the G20.

These are, if you will, second-order deadlocks in the sense that they don't involve irreconcilable differences among the three big players. The EU and the US tend to think that many of these problems could be finessed with increased aid offers - though the possibility of buying off the G33 with a fat check is highly iffy. The thing that sort of staggered me about the negotiation simulation was realizing that even if the Triangular Deadlock magically disappeared tomorrow, the second-order deadlocks could well be deep enough to prevent an agreement.

At the end of all this, I'm left with a much more nuanced understanding not just of why there has been deadlocked, but also of why the deadlock has overpowered every attempt at a solution. Though trade diplomats are still hammering away on the round in Geneva, it's not hard to see that these are pro-forma efforts. On the whole the round has been given up as hopeless.

My guess is that in the next few months, the WTO's Director General will be forced to acknowledge that the existing differences cannot be bridged, and the round will go into a sort of deep freeze. Interestingly, there is no settled method to officially bury the corpse of a round, so negotiations would likely be suspended rather than ended, in the hope that they can be revived, somehow, at some point down the line. In the meantime, the US and the EU would concentrate on hammering out bilateral deals to advance their trade interests, and the G20, G33 and ACP would rely more and more on the WTO's existing dispute-settlement system to advance theirs.

Historical experience, however, suggests that when trade negotiations are not moving forward, the tendency is for countries to resort to more and more protectionism. If the de facto failure of the round leads to considerable backsliding, then it's imaginable that in a few years the big players will come back to the negotiating table with a renewed sense of mission. If, in the meantime, the US and France elect themselves presidents who are more committed to multilateralism, then its just about imaginable that the round could rise from the ashes sometime around 2009. Until then, though, it's dead. It's deader than dead.