Maybe the French Agriculture minister had a point after all. Chuck Grassley, the powerful head of the US Senate's Agriculture Committee, has just said the US Congress is unlikely to approve the deal being hammered out in Hong Kong. After 48 hours of intensive, sleep-deprived negotiating, his comments did not go down well here.

Credit where it's due: a lot of European delegates (off the record) and lefty NGOs (on the record) here have been questioning US Trade Representative Rob Portman's ability to deliver the kind of deal he's been promising, noting that he seems to have been going well beyond his Fast-Track negotiating mandate and making promises to the developing world the US congress would never agree to.

It's a slightly bizarre argument, however, because the draft Grassley is pledging to kill in Congress is not likely to even be signed here. Peter Mandelson - Hong Kong's Dr. No - spent the night taking shots at it, and taking the EU's isolation here from "near-total" to total.

If nothing else, this week has made me incredibly cynical about the EU. These bastards spin with such brazen disregard for the truth, it's staggering. A lot of their statements are just near-Orwelian reversals of what happened - Eurasia has always been at war with Eastasia and the meeting is failing due to developing country intransigence. Right.

If the Euro chingo doesn't get us, the US congressional sin-nariz will. Meanwhile, Portman keeps making concessions. One interpretation is that he is so confident the EU won't sign anything like what they're talking about, he feels emboldened to make "concessions for free" - knowing he won't really have to take them to congress. Hey, why should the US share the bad-guy spotlight when the EU is willing to hog it all to itself?

Beyond all the tactical posturing, the big losers from all of this will be West Africa's cotton producers. A group including Burkina Faso, Mali, Chad, and Niger - really the poorest of the poor countries on earth - came excruciatingly close to reaching a hard fought for agreement with the US on cotton subsidies. To these countries Cotton is a bit like oil is to Venezuela - 70% of their export earnings, basically their only export commodity. Their producers' inability to compete with subsidized US producers had become a kind of symbol of the iniquities in the trade regime: millions and millions of desperately poor Africans shut out of world markets by the US determination to keep paying subsidies for 50,000 gringos to farm cotton. This week, Brazil, India and the G110 went to bat for the West African cotton producing countries, pressuring the US as a block to make cuts in cotton subsidies faster than cuts in any other sector.

They were just about there...the US had just about conceded the point...they were so, so close. But no cigar, cuz the EU won't sign.

December 17, 2005

Fussing over ag subsidies...

Confused about what the big WTO fight over agriculture is all about? Pietra Rivoli writes a lucid little summary of the main issue and the way it's gotten distorted in negotiations. She exaggerates when she says the talks have become "single issue", but other than that her exposition is flawless...

December 16, 2005

Mandelson's Straightjacket

[Sorry to stay stuck on the Hong Kong thing, everyone, but I thought it was time to demonstrate I can be obsessed with more than one thing at a time!]

It's day four of the Hong Kong WTO Ministerial and the conference has officially entered the tired-and-cranky stage. Hey, it's not me saying it, that's how the Deputy US Trade Representative put it at her press conference today. In her view, you need to get to this point before people start negotiating in earnest. If so, we're primed for some earnest negotiatin', cuz tired-and-cranky fits the atmosphere here to a T.

Fact is, nobody is really expecting a breakthrough here today. It's now painfully clear that the EU is just not going to improve its offer, and its offer is very far from acceptable to the developing country block. It's not that Peter Mandelson, the EU Trade Commissioner, doesn't want to sweeten the deal, it's that he can't: the whole institutional structure of the European Union conspires against it.

Fact is, nobody is really expecting a breakthrough here today. It's now painfully clear that the EU is just not going to improve its offer, and its offer is very far from acceptable to the developing country block. It's not that Peter Mandelson, the EU Trade Commissioner, doesn't want to sweeten the deal, it's that he can't: the whole institutional structure of the European Union conspires against it.

See, unlike all the other negotiators here, his crankiness Peter Mandelson is not a minister. He's more like a gofer for the 25 EU trade ministers, who are the ones who ultimately get to set EU trade policy. The ministers meet, they set out a harmonized EU negotiating mandate, and they hand it to him. The EU mandate itself is the outcome of a long, difficult, involved negotiation between 25 very different countries with very different interests. By the time the 25 have worked out a common position, there's basically no wiggle room left. Mandelson can't change even the details of the EU's offer without upsetting the delicate balance embodied in the mandate: take out one comma here and the French throw a fit, switch a "shall" to a "should" there and the Hungarians go ballistic.

So there's a strange imbalance between the way the EU "negotiates" at a WTO ministerial and the way everyone else does. When the Australians and the Americans sit down to discuss State Trading Enterprises, for instance, both sides have leeway to explore creative solutions to their disagreement. They can haggle, they can give and take, they can explore different possibilities. But the EU can't do any of that. When Mandelson walks into the negotiating room, all he's really allowed to do is restate his mandate. Which is why I put "negotiate" in scare-quotes above: the EU doesn't really negotiate at all at these things. It reiterates. Often at great length, and with some top grade spin, granted, but its underlying position never changes. As I'm sure you can imagine, this is incredibly frustrating for all the other delegations.

Certainly, things have come to a head when the Financial Times, the FT ferchrissake, is running stories about the EU facing "near-total isolation" in the talks.

At one of the press conferences today, one journo who'd obviously reached the tired-and-cranky stage asked the French trade minister what the point is of even having ministerials if the EU can't and won't change its offer. The guy answered, a bit lamely in my view, that at least the other countries know that it's a credible offer since it's been pre-approved by all the EU member governments, whereas anything the US offers could still get shot down when it goes up for congressional approval in Washington. Perhaps. But it remains hypothetical because, as long as the EU remains lost in its own private bureaucratic laberynth, there won't be a trade agreement for the US congress to vote on.

It's day four of the Hong Kong WTO Ministerial and the conference has officially entered the tired-and-cranky stage. Hey, it's not me saying it, that's how the Deputy US Trade Representative put it at her press conference today. In her view, you need to get to this point before people start negotiating in earnest. If so, we're primed for some earnest negotiatin', cuz tired-and-cranky fits the atmosphere here to a T.

Fact is, nobody is really expecting a breakthrough here today. It's now painfully clear that the EU is just not going to improve its offer, and its offer is very far from acceptable to the developing country block. It's not that Peter Mandelson, the EU Trade Commissioner, doesn't want to sweeten the deal, it's that he can't: the whole institutional structure of the European Union conspires against it.

Fact is, nobody is really expecting a breakthrough here today. It's now painfully clear that the EU is just not going to improve its offer, and its offer is very far from acceptable to the developing country block. It's not that Peter Mandelson, the EU Trade Commissioner, doesn't want to sweeten the deal, it's that he can't: the whole institutional structure of the European Union conspires against it.See, unlike all the other negotiators here, his crankiness Peter Mandelson is not a minister. He's more like a gofer for the 25 EU trade ministers, who are the ones who ultimately get to set EU trade policy. The ministers meet, they set out a harmonized EU negotiating mandate, and they hand it to him. The EU mandate itself is the outcome of a long, difficult, involved negotiation between 25 very different countries with very different interests. By the time the 25 have worked out a common position, there's basically no wiggle room left. Mandelson can't change even the details of the EU's offer without upsetting the delicate balance embodied in the mandate: take out one comma here and the French throw a fit, switch a "shall" to a "should" there and the Hungarians go ballistic.

So there's a strange imbalance between the way the EU "negotiates" at a WTO ministerial and the way everyone else does. When the Australians and the Americans sit down to discuss State Trading Enterprises, for instance, both sides have leeway to explore creative solutions to their disagreement. They can haggle, they can give and take, they can explore different possibilities. But the EU can't do any of that. When Mandelson walks into the negotiating room, all he's really allowed to do is restate his mandate. Which is why I put "negotiate" in scare-quotes above: the EU doesn't really negotiate at all at these things. It reiterates. Often at great length, and with some top grade spin, granted, but its underlying position never changes. As I'm sure you can imagine, this is incredibly frustrating for all the other delegations.

Certainly, things have come to a head when the Financial Times, the FT ferchrissake, is running stories about the EU facing "near-total isolation" in the talks.

At one of the press conferences today, one journo who'd obviously reached the tired-and-cranky stage asked the French trade minister what the point is of even having ministerials if the EU can't and won't change its offer. The guy answered, a bit lamely in my view, that at least the other countries know that it's a credible offer since it's been pre-approved by all the EU member governments, whereas anything the US offers could still get shot down when it goes up for congressional approval in Washington. Perhaps. But it remains hypothetical because, as long as the EU remains lost in its own private bureaucratic laberynth, there won't be a trade agreement for the US congress to vote on.

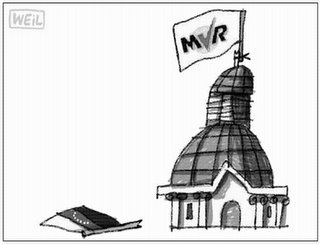

Venezuela electoral results watch, Day 12 or how I stopped worrying and learned to love the CNE.

Venezuela has no final electoral results so far. This, despite the fact that the Venezuelan Ministry of Electoral Affairs, which is controled directly by the Vice-President's office, touts the Venezuelan Electoral system as being the safest, most transparent, fastest and fairest of them all worldwide. This, despite the fact that the Venezuelan M.E.A. (the artist formerly known as CNE) spent Millions of dollars on machines the SENIAT (another one of the new weapons of mass coercion the government has put in use against who oppose it) deemed too unsafe to be used as lottery terminals. This, despite the fact that by Sunday Dec. 4th at night the M.E.A. had supposedly tallied 75% of the vote. This, despite the fact that only one faction was disputing seats in the Assembly. This, despite the fact that the first round of Chilean elections had tallied a national final result by the evening of the very same day the election took place.

The Minister of Electoral Affairs, the Spa-loving, massage-receiving, objective-criticism-only-accepting 'straight arrow' Dr. Jorge Rodríguez, has made miryad public appearances these days. He has even given press conferences where he has attacked the EU/OAS observator mission report as biased, and has left possibilities open to accept "objective" criticism. He has yet to give final, final numbers.

The Minister of Electoral Affairs, the Spa-loving, massage-receiving, objective-criticism-only-accepting 'straight arrow' Dr. Jorge Rodríguez, has made miryad public appearances these days. He has even given press conferences where he has attacked the EU/OAS observator mission report as biased, and has left possibilities open to accept "objective" criticism. He has yet to give final, final numbers.

Celso Amorim's Ministerial

Brazilian foreign minister Celso Amorim is having the time of his life this week. After a quarter century of grandiose but empty declarations of developing country unity on trade issues, Hong Kong has finally sealed the deal. Amorim is acting as the de facto leader of the Brazil-India alliance, which is at the heart of the G20 group of developing nations, which has roped in the G33 and G90 groups of developing nations and includes 110 countries and 80% of the world population. India and Brazil have been deliberate about working out common negotiating positions with the other developing country groups, and they seem to have overcome the poorest countries' initial reticence in this regard.

The outcome of all this coordinating is that for the first time the developing countries really are negotiating as a block...and Amorim is at the center of it all. More and more, he speaks not for Brazil but for the whole of the developing world here. And, having gotten control the agenda, Amorim is driving one hard bargain. He's not giving an inch to the EU, and he has outflanked the EU so comprehensibly in the PR war surrounding the negotiations that when the meeting fails, it'll be the Europeans who take the fall. Honestly, I think it's marvelous...

Again, the outcome of this will not be a development-friendly agreement, at least not immediately. There's no chance for "full negotiating modalities" to be agreed here and there may not even be any agreement at all. The difference this time around is that the EU is going to take the blame, not the developing countries. It's never happened before, and it sets up a very different atmosphere for the rest of the Doha Round. The developing countries will keep the initiative while Europe take a defensive position, making increasingly unconvincing excuses for blocking progress. Given that that the ministerial was never really likely to succeed in producing a complete outline agreement, this is the best outcome the developing world could have hoped for. And Amorim deserves a lot of the credit for that.

December 15, 2005

The WTO Turned on its Head

It's day 3 in Hong Kong and I have to say this conference is full of surprises. Figuring I'd been spending enough time with third world types, I decided to go to the International Manufacturers' Association press conference. I walk into the room and realize I am the only "journalist" who's turned up. So I sit down and there they all are, the heads of every major employers' federation in Europe and North America, lined up in front of me. Undeterred, the chairman launches straight into the "press conference" except, well, there are about 20 of them and only one of me. So I get to ask all the questions, these guys just take turns answering.

It was totally bizarre, really: a press conference in reverse. Still - and even though I was totally unprepared to be put on the spot like that - it's not a chance you pass up. So I started asking questions. And let me tell you, I got a lot of frustration in response.

See, these guys came to Hong Kong to talk about industrial tariffs, about service liberalization, about the stuff giant multinationals care about. But nobody's talking about that. All the negotiations are focused on agriculture. The big employers' federations are totally sidelined, and seemingly at a loss as to how to get a handle on the agenda again. It's definitely not a good sign when they call a press conference and the only news organization that turns up is VenEconomy.

It's symptomatic, though: what we're seeing is the WTO turned on its head. All the old cliches about the WTO as multinational conspiracy look more and more out of touch. When I started researching this stuff, one of my professors told me that 90% of the trick to multilateral negotiations is taking control of the agenda. The multinationals used to have it, but they lost it, and they seem totally bewildered about what went wrong. In Hong Kong, the big developing countries have taken hold of the agenda and they're just not going to let go. It's fascinating.

The big story of the day is definitely the increasing isolation of the EU, though. More and more the US position on agriculture sounds like the developing countries' position. You can see this in the language negotiators are using when they talk to the press: Brazil and India have been describing agriculture as the "key that could unlock the negotiations" and, this morning, US Trade Representative Rob Portman used exactly that phrase. Brazil and India insist that the first priority is establishing 2010 as a definite deadline for eliminating all agricultural export subsidies. Portman agrees emphatically.

The Europeans, meanwhile, keep insisting on "balance" between agriculture and other issues, and they keep dithering on a deadline on agricultural export subsidies. Thing is, nobody's biting.

All of this is unprecedented. Never had developing countries taken the lead in a WTO ministerial like they're doing this week. Never had the big developed countries looked as divided as they do now. And, certainly, never had we seen the US take sides - in general terms, if not on the details - with the developing countries rather than with Europe.

At the same time, India and Brazil are very much aware that many developing countries - and especially the least developed countries - are worried they'll get sold out. In 2004, the US and the EU clearly tried to engineer an agreement that took on India and Brazil's concerns, but nobody else's. India and Brazil are not playing along this week. India's trade minister, Kamal Nath, is spending a lot of time coordinating with the other developing countries to make sure they present a unified position. The LDC delegates I've spoken to seem, if not exactly comfortable, at least reasonably reassured that India and Brazil are not going to cut a deal without consulting them first.

In the end, it doesn't really change anything, because the EU is totally entrenched in its stance and it's not going to budge without big concessions. So nobody really expects a deal on full negotiating modalities to come out of this, which was supposed to be the point. What's clear, though, is that when it's all said and done the EU is going to have to take the fall for the failure of the talks.

Which is why Celso Amorim, the Brazilian foreign minister, is one happy camper in Hong Kong. The Europeans thought they could divide the developing country block, picking them off with selective concessions. A lot of LDCs see their offers on "aid for trade" in just that light. It's emphatically not working. If nothing else, Hong Kong is decisively consolidating the joint Indian-Brazilian leadership of the developing country block.

It was totally bizarre, really: a press conference in reverse. Still - and even though I was totally unprepared to be put on the spot like that - it's not a chance you pass up. So I started asking questions. And let me tell you, I got a lot of frustration in response.

See, these guys came to Hong Kong to talk about industrial tariffs, about service liberalization, about the stuff giant multinationals care about. But nobody's talking about that. All the negotiations are focused on agriculture. The big employers' federations are totally sidelined, and seemingly at a loss as to how to get a handle on the agenda again. It's definitely not a good sign when they call a press conference and the only news organization that turns up is VenEconomy.

It's symptomatic, though: what we're seeing is the WTO turned on its head. All the old cliches about the WTO as multinational conspiracy look more and more out of touch. When I started researching this stuff, one of my professors told me that 90% of the trick to multilateral negotiations is taking control of the agenda. The multinationals used to have it, but they lost it, and they seem totally bewildered about what went wrong. In Hong Kong, the big developing countries have taken hold of the agenda and they're just not going to let go. It's fascinating.

The big story of the day is definitely the increasing isolation of the EU, though. More and more the US position on agriculture sounds like the developing countries' position. You can see this in the language negotiators are using when they talk to the press: Brazil and India have been describing agriculture as the "key that could unlock the negotiations" and, this morning, US Trade Representative Rob Portman used exactly that phrase. Brazil and India insist that the first priority is establishing 2010 as a definite deadline for eliminating all agricultural export subsidies. Portman agrees emphatically.

The Europeans, meanwhile, keep insisting on "balance" between agriculture and other issues, and they keep dithering on a deadline on agricultural export subsidies. Thing is, nobody's biting.

All of this is unprecedented. Never had developing countries taken the lead in a WTO ministerial like they're doing this week. Never had the big developed countries looked as divided as they do now. And, certainly, never had we seen the US take sides - in general terms, if not on the details - with the developing countries rather than with Europe.

At the same time, India and Brazil are very much aware that many developing countries - and especially the least developed countries - are worried they'll get sold out. In 2004, the US and the EU clearly tried to engineer an agreement that took on India and Brazil's concerns, but nobody else's. India and Brazil are not playing along this week. India's trade minister, Kamal Nath, is spending a lot of time coordinating with the other developing countries to make sure they present a unified position. The LDC delegates I've spoken to seem, if not exactly comfortable, at least reasonably reassured that India and Brazil are not going to cut a deal without consulting them first.

In the end, it doesn't really change anything, because the EU is totally entrenched in its stance and it's not going to budge without big concessions. So nobody really expects a deal on full negotiating modalities to come out of this, which was supposed to be the point. What's clear, though, is that when it's all said and done the EU is going to have to take the fall for the failure of the talks.

Which is why Celso Amorim, the Brazilian foreign minister, is one happy camper in Hong Kong. The Europeans thought they could divide the developing country block, picking them off with selective concessions. A lot of LDCs see their offers on "aid for trade" in just that light. It's emphatically not working. If nothing else, Hong Kong is decisively consolidating the joint Indian-Brazilian leadership of the developing country block.

Is there anything he can't do?

In his spare time from trying to save the World Trade Regime, WTO Director General Pascal Lamy is blogging the Ministerial...

Beginners' Guide to WTOese: "A Balanced Agreement"

I think a big part of the reason people find the WTO so hard to understand is that trade diplomats refuse on principle to speak plain English. Now, I know every specialized organization breeds its own specialized lingo, and the more specialized it is the more convoluted it gets...but at the WTO this dynamic has gone totally haywire.

Some of it is downright oxymoronic. It takes some immersion in this absurd little world before you realize that "most favored nation" (MFN) status means exactly the opposite of what it says: you're allowed to treat a given trade partner better than MFN (by signing a free-trade agreement with that partner, for instance) but you're not allowed to treat a partner worse. So actually, your most favored nation trade partners are the ones you favor the least.

Some of it is just mystifying: I have no clue at all why they have to say "full negotiating modalities" when what they mean is "an agreement."

Other elements of WTOese are really just bureaucratic euphemisms: "sensitive products" means roughly "whatever I'm being lobbied not to liberalize." "An ambitious agreement" means "you liberalize what I want you to liberalize but I get to protect my sensitive products." "Frank discussions" seems to mean "ministers tiresomly reiterating positions they've held for years." So if you see a WTO talking head on the news saying "ministers held frank discussions on full negotiating modalities for sensitive products aimed at reaching an ambitious agreement" you can just throw your hands up in utter despair.

But the particular linguistic deformation that caught my eye today is that most slippery of WTOese formulations: "a balanced agreement."

Every single delegation here claims to be working towards "a balanced agreement." Needless to say, no two ministers mean the same thing by the phrase. For the rich countries, "a balanced agreement" means "you liberalize your manufacturing markets and we'll liberalize our agricultural markets." For developing countries it means "we already liberalized our manufacturing markets last, so now you have to liberalize your agricultural markets." They use the exact same phrase, but they mean diametrically opposed things.

The reason I think, is something I alluded to yesterday. During the last round of trade negotiations - the famous Uruguay Round that dragged on from 1986 to 1994 - developing countries made major concessions on a whole range of issues and got pathetically little in return in terms of agriculture. The rich countries considered the Uruguay Round agreements "balanced" just because, for the first time, they introduced some (weak) rules on agricultural trade. More or less all the developing countries now believe the Uruguay Round agreement was seriously unbalanced - "forced consensus" at its worst.

Now the consequences of that unbalance are being worked through the system. Call it Uruguay Overhang. From the developing countries' point of view, the whole point of the current round of negotiations is to "balance" the iniquities of the previous round. Really, what the developing world wants is not so much a "balanced agreement" as a "balancing agreement"

Initially, the rich countries implicitly agreed, officially calling the current round the "Doha Development Agenda" in recognition that Uruguay was not exactly development friendly. But in the four years since Doha, calls for a "balanced agreement" have come back with a vengeance, especially in the EU. Sure, they still talk in terms of development, but more and more they're demanding a quid-pro-quo.

India and Brazil put the developing countries' position pretty succinctly yesterday. What they say, in paraphrase, is "hey, every time we meet them, the Europeans ask us what price we're willing to pay in exchange for them to stop doing things they shouldn't be doing in the first place."

The EU is desperate to spin its way out of this bind. Every time Peter Mandelson, the EU trade commissioner, comes anywhere near a microphone he says "balance" at least once sentence. The developing countries have to balance their demands for better agricultural market access with concessions on manufacturing tariffs. The US has to balance its call for dramatic farm tariff cuts by reforming its Food Aid programs. Canada, Australia and New Zealand need to "balance" by reforming their State Agricultural Trading Enterprises.

"Balance", in this context, means roughly "what's in it for me?!" Fluffy development rhetoric aside, the EU won't seriously consider farther farm trade concessions until they've extracted their pound of flesh on other issues. Some of the US delegates I've met put it even more bluntly: "they know if the conversation is about agriculture they're screwed, they're desperate to change the subject."

The funny thing is that the US is arguably closer to the developing countries' position than to the EU on all of this. The reason is not any newfound philanthropic thrust to the Bush administration: it's just that American agribusiness is big enough and efficient enough to compete in a low-or-no tariff world. European farmers, by and large, are not. For the US, a liberal farm market is a business opportunity. For the EU, it would be a bureaucratic dust bowl.

Which, I think, is pretty interesting. Most people tend to assume that the US is the baddie at the WTO. Bush country and all that. But the reality is that if anyone looks isolated in all this it's Europe. The difference between the US and the Brazil/India proposals are mostly technical in nature - if it was up to them, they could sit down and work out a compromise in half an hour. The real, substantive gap in agriculture is between the US/Brazil/India on the one hand and the EU on the other.

Some of it is downright oxymoronic. It takes some immersion in this absurd little world before you realize that "most favored nation" (MFN) status means exactly the opposite of what it says: you're allowed to treat a given trade partner better than MFN (by signing a free-trade agreement with that partner, for instance) but you're not allowed to treat a partner worse. So actually, your most favored nation trade partners are the ones you favor the least.

Some of it is just mystifying: I have no clue at all why they have to say "full negotiating modalities" when what they mean is "an agreement."

Other elements of WTOese are really just bureaucratic euphemisms: "sensitive products" means roughly "whatever I'm being lobbied not to liberalize." "An ambitious agreement" means "you liberalize what I want you to liberalize but I get to protect my sensitive products." "Frank discussions" seems to mean "ministers tiresomly reiterating positions they've held for years." So if you see a WTO talking head on the news saying "ministers held frank discussions on full negotiating modalities for sensitive products aimed at reaching an ambitious agreement" you can just throw your hands up in utter despair.

But the particular linguistic deformation that caught my eye today is that most slippery of WTOese formulations: "a balanced agreement."

Every single delegation here claims to be working towards "a balanced agreement." Needless to say, no two ministers mean the same thing by the phrase. For the rich countries, "a balanced agreement" means "you liberalize your manufacturing markets and we'll liberalize our agricultural markets." For developing countries it means "we already liberalized our manufacturing markets last, so now you have to liberalize your agricultural markets." They use the exact same phrase, but they mean diametrically opposed things.

The reason I think, is something I alluded to yesterday. During the last round of trade negotiations - the famous Uruguay Round that dragged on from 1986 to 1994 - developing countries made major concessions on a whole range of issues and got pathetically little in return in terms of agriculture. The rich countries considered the Uruguay Round agreements "balanced" just because, for the first time, they introduced some (weak) rules on agricultural trade. More or less all the developing countries now believe the Uruguay Round agreement was seriously unbalanced - "forced consensus" at its worst.

Now the consequences of that unbalance are being worked through the system. Call it Uruguay Overhang. From the developing countries' point of view, the whole point of the current round of negotiations is to "balance" the iniquities of the previous round. Really, what the developing world wants is not so much a "balanced agreement" as a "balancing agreement"

Initially, the rich countries implicitly agreed, officially calling the current round the "Doha Development Agenda" in recognition that Uruguay was not exactly development friendly. But in the four years since Doha, calls for a "balanced agreement" have come back with a vengeance, especially in the EU. Sure, they still talk in terms of development, but more and more they're demanding a quid-pro-quo.

India and Brazil put the developing countries' position pretty succinctly yesterday. What they say, in paraphrase, is "hey, every time we meet them, the Europeans ask us what price we're willing to pay in exchange for them to stop doing things they shouldn't be doing in the first place."

The EU is desperate to spin its way out of this bind. Every time Peter Mandelson, the EU trade commissioner, comes anywhere near a microphone he says "balance" at least once sentence. The developing countries have to balance their demands for better agricultural market access with concessions on manufacturing tariffs. The US has to balance its call for dramatic farm tariff cuts by reforming its Food Aid programs. Canada, Australia and New Zealand need to "balance" by reforming their State Agricultural Trading Enterprises.

"Balance", in this context, means roughly "what's in it for me?!" Fluffy development rhetoric aside, the EU won't seriously consider farther farm trade concessions until they've extracted their pound of flesh on other issues. Some of the US delegates I've met put it even more bluntly: "they know if the conversation is about agriculture they're screwed, they're desperate to change the subject."

The funny thing is that the US is arguably closer to the developing countries' position than to the EU on all of this. The reason is not any newfound philanthropic thrust to the Bush administration: it's just that American agribusiness is big enough and efficient enough to compete in a low-or-no tariff world. European farmers, by and large, are not. For the US, a liberal farm market is a business opportunity. For the EU, it would be a bureaucratic dust bowl.

Which, I think, is pretty interesting. Most people tend to assume that the US is the baddie at the WTO. Bush country and all that. But the reality is that if anyone looks isolated in all this it's Europe. The difference between the US and the Brazil/India proposals are mostly technical in nature - if it was up to them, they could sit down and work out a compromise in half an hour. The real, substantive gap in agriculture is between the US/Brazil/India on the one hand and the EU on the other.

December 14, 2005

Not your grandfather's WTO

Well, I know most of you don't come here looking for WTO news, but I'm in Hong Kong now so WTO news is what yer gonna get! Sorry to the ghosts for this, but this stuff is too interesting, I can't hold back.

I spent the morning hanging out with a group of Least Developed Country delegates. It didn't take long to realize the dynamics have changed dramatically for them since the last WTO Ministerial Conference in Cancun two years ago. What's remarkable is that you don't hear any more complaints about process from the LDCs. This is definitely new. In Cancun, the poorest countries were furious about the process: the Mexican organizers presented drafts for agreement at the last minute, texts negotiated behind closed doors by the big trade powers that uniformly ignored LDC concerns and bore no relation to what had been negotiating in the months before the conference. The bad blood this "forced consensus" tactic generated had a lot to do with the collapse of Cancun. India, Kenya and Brazil refused to play along and just walked out. It was a fiasco.

The contrast this time around is startling. The Bangladeshi Trade Minister spoke glowingly of the "bottom-up" approach now in place - the texts presented for agreement this week are the same ones they have been negotiating since July 2004. The question is no longer whether to substantially liberalize agriculture at all, but how much, and how fast. "Trade for aid" has received a lot of attention in the first two days - with the US, the EU and Japan all offering substantial new sums of money to help LDCs take advantage of the new market opportunities an agreement would offer.

This doesn't mean the LDCs are thrilled about the way the negotiations are going: there are still very wide differences with the rich countries on basically all the issues, and some LDCs are suspicious that the trade for aid stuff is just an attempt to buy them off. But it does mean that LDCs no longer feel railroaded into signing stuff they've barely read. This is a lot different from the situation two years ago.

One sign of the improved atmosphere is the relatively small scale of the demonstrations outside. While there have been some protests, and a couple of fairly rowdy ones, the city itself feels normal. Certainly there's been nothing like the disruptions in Cancun or the utter chaos in Seattle. As the Zambian trade minister said, a big reason for this is that, this time around, most of the pro-south NGOs are inside the negotiating hall lobbying delegates rather than outside protesting - a shift that's both substantive and symbolic.

Most of the credit for this goes to Pascal Lamy - the former EU Trade Commissioner who's now the Director General of WTO. Lamy is one smooth operator, obviously way more competent than his predecesors. The conference is teeming with NGOs big and small, north and south. A lot of LDC ministers seem to genuinely appreciate the way he's handled the issue.

Unfortunately, Lamy tiene razon pero va preso. Trouble is, as soon as you stop trying to "manufacture consensus" you're left with the uncomfortable fact that there isn't really an underlying consensus - Europe and Japan are just not willing to liberalize their agricultural market to anything like the extent developing countries want to see, and developing countries are not willing to re-edit their mistakes from the last round, when they made specific commitments to liberalize manufacturing trade before securing specific commitments on agriculture.

Cancun showed that forced consensus is just not acceptable to developing countries anymore. Lamy deserves credit for understanding that much - but that doesn't magically shift the negotiating positions closer together somehow. The paradoxical result is that at the same time that LDCs praise the new, more transparent process, there's universal gloom about the prospects of signing anything meaningful this week - and a real sense that the Doha Round as a whole could fail. The alternative to forced consensus is not genuine consensus - it's deadlock.

Lamy, the sneaky frog, is determined to avoid a repeat of the embarrassment in Cancun. Counting the mess in Seattle back in 1999, a collapse this week would be the third WTO fiasco out of the last four ministerials. There's real concern that the WTO system would not recover from yet another P.R. disaster on that scale, so Lamy's watchword is "recalibrating expectations" - meaning he wants everyone to agree on something, even if it's not the "full modalities" they were originally supposed to hammer out in Hong Kong. ("Full modalities" is WTOese for "an outline agreement that resolves all the really difficult issues.") Given Lamy's near rock-star status around here, I bet he'll get his way. Come Sunday, you'll probably see ministers lining up to sign a piece of paper. It won't be the piece of paper they came here to sign, but it'll be something.

I spent the morning hanging out with a group of Least Developed Country delegates. It didn't take long to realize the dynamics have changed dramatically for them since the last WTO Ministerial Conference in Cancun two years ago. What's remarkable is that you don't hear any more complaints about process from the LDCs. This is definitely new. In Cancun, the poorest countries were furious about the process: the Mexican organizers presented drafts for agreement at the last minute, texts negotiated behind closed doors by the big trade powers that uniformly ignored LDC concerns and bore no relation to what had been negotiating in the months before the conference. The bad blood this "forced consensus" tactic generated had a lot to do with the collapse of Cancun. India, Kenya and Brazil refused to play along and just walked out. It was a fiasco.

The contrast this time around is startling. The Bangladeshi Trade Minister spoke glowingly of the "bottom-up" approach now in place - the texts presented for agreement this week are the same ones they have been negotiating since July 2004. The question is no longer whether to substantially liberalize agriculture at all, but how much, and how fast. "Trade for aid" has received a lot of attention in the first two days - with the US, the EU and Japan all offering substantial new sums of money to help LDCs take advantage of the new market opportunities an agreement would offer.

This doesn't mean the LDCs are thrilled about the way the negotiations are going: there are still very wide differences with the rich countries on basically all the issues, and some LDCs are suspicious that the trade for aid stuff is just an attempt to buy them off. But it does mean that LDCs no longer feel railroaded into signing stuff they've barely read. This is a lot different from the situation two years ago.

One sign of the improved atmosphere is the relatively small scale of the demonstrations outside. While there have been some protests, and a couple of fairly rowdy ones, the city itself feels normal. Certainly there's been nothing like the disruptions in Cancun or the utter chaos in Seattle. As the Zambian trade minister said, a big reason for this is that, this time around, most of the pro-south NGOs are inside the negotiating hall lobbying delegates rather than outside protesting - a shift that's both substantive and symbolic.

Most of the credit for this goes to Pascal Lamy - the former EU Trade Commissioner who's now the Director General of WTO. Lamy is one smooth operator, obviously way more competent than his predecesors. The conference is teeming with NGOs big and small, north and south. A lot of LDC ministers seem to genuinely appreciate the way he's handled the issue.

Unfortunately, Lamy tiene razon pero va preso. Trouble is, as soon as you stop trying to "manufacture consensus" you're left with the uncomfortable fact that there isn't really an underlying consensus - Europe and Japan are just not willing to liberalize their agricultural market to anything like the extent developing countries want to see, and developing countries are not willing to re-edit their mistakes from the last round, when they made specific commitments to liberalize manufacturing trade before securing specific commitments on agriculture.

Cancun showed that forced consensus is just not acceptable to developing countries anymore. Lamy deserves credit for understanding that much - but that doesn't magically shift the negotiating positions closer together somehow. The paradoxical result is that at the same time that LDCs praise the new, more transparent process, there's universal gloom about the prospects of signing anything meaningful this week - and a real sense that the Doha Round as a whole could fail. The alternative to forced consensus is not genuine consensus - it's deadlock.

Lamy, the sneaky frog, is determined to avoid a repeat of the embarrassment in Cancun. Counting the mess in Seattle back in 1999, a collapse this week would be the third WTO fiasco out of the last four ministerials. There's real concern that the WTO system would not recover from yet another P.R. disaster on that scale, so Lamy's watchword is "recalibrating expectations" - meaning he wants everyone to agree on something, even if it's not the "full modalities" they were originally supposed to hammer out in Hong Kong. ("Full modalities" is WTOese for "an outline agreement that resolves all the really difficult issues.") Given Lamy's near rock-star status around here, I bet he'll get his way. Come Sunday, you'll probably see ministers lining up to sign a piece of paper. It won't be the piece of paper they came here to sign, but it'll be something.

December 13, 2005

Casualties of War

I got an email today summarizing violence statistics in Venezuela and figured they were worth running with. See, the Chávez administration claims to care much about people dying overseas in US-led wars, but yet the deaths of tens of thousands of Venezuelans in unexplained ways does not even cause a blip in El Comandane's radar. It is so not an issue for the Bolivarians that there is not even a Mission to address the issue of crime. But numbers speak louder than words.

Crime is the second problem in the minds of Venezuelans after unemployment.

Government statistics say that between 1999 and 2003, 58,519 people were murdered.

In 2003, there were 15,738 murders, an average of 43 murders per day, almost 2 per hour.

Projections indicate that by 2005, the total number of murders since Chávez came to power will number 95,570 people. Say that out loud: 95 thousand murders.

By 2003, the increase in the murder rate was 244.11% relative to 1998. By 2005, the same increase is projected to be 301.76% relative to 1998's rate.

Murders are the third cause of death in Venezuela. Among adult males, they are the first cause of death. Think about that: Venezuelan males are more likely to die murdered than by heart disease or automobile accidents.

Of the 58,519 murders committed, 23,606 (roughly 40%) of these were of people between 15 and 24 years of age.

94.03% of the 23,606 young people murdered were young men.

6 out of 10 people between 15 and 24 who die in Venezuela are murdered. 7 of every 10 young men between the ages of 15 and 24 who died were murdered.

Of all the murders committed between 1999 and 2003, 82% of them were caused by firearms. Think about this: Faced with this context, Mr. Chávez has decided to purchase hundreds of thousands of weapons to arm his personal militias.

Now, I challenge any PSF to convince me this is something the government is actually doing something about. Well, something other than blaming the CIA.

(Thanks to Raul Fatarella for the numbers)

Crime is the second problem in the minds of Venezuelans after unemployment.

Government statistics say that between 1999 and 2003, 58,519 people were murdered.

In 2003, there were 15,738 murders, an average of 43 murders per day, almost 2 per hour.

Projections indicate that by 2005, the total number of murders since Chávez came to power will number 95,570 people. Say that out loud: 95 thousand murders.

By 2003, the increase in the murder rate was 244.11% relative to 1998. By 2005, the same increase is projected to be 301.76% relative to 1998's rate.

Murders are the third cause of death in Venezuela. Among adult males, they are the first cause of death. Think about that: Venezuelan males are more likely to die murdered than by heart disease or automobile accidents.

Of the 58,519 murders committed, 23,606 (roughly 40%) of these were of people between 15 and 24 years of age.

94.03% of the 23,606 young people murdered were young men.

6 out of 10 people between 15 and 24 who die in Venezuela are murdered. 7 of every 10 young men between the ages of 15 and 24 who died were murdered.

Of all the murders committed between 1999 and 2003, 82% of them were caused by firearms. Think about this: Faced with this context, Mr. Chávez has decided to purchase hundreds of thousands of weapons to arm his personal militias.

95.28% of the murders of young men between 15 and 24 were caused by firearms.

Now, I challenge any PSF to convince me this is something the government is actually doing something about. Well, something other than blaming the CIA.

(Thanks to Raul Fatarella for the numbers)

Hong Kong Chronicles: Damn farmers

Well, it's day 1 of the WTO ministerial conference, and my first Hong Kong insight comes in the form of a question - how did farmers get so damn powerful?

It's really strange...we're here in this super high-tech city, surrounded by ultramodern skyscrapers, chips, factories, computers, and you gather 149 of the most powerful people in the world to talk about the sparkling, gleaming hyperglobalized world economy of the 21st century and what do they talk about? They talk about Cain and Abel's profession! They talk about a business that's reached maturity roughly 3000 years ago!

The whole organization has been stuck on the agriculture issue for years. Big agricultural producers in the third world want much better access to first world markets - particularly Europe and Japan. Europe, Japan, and to a lesser extent the US want to continue protecting their farmers with subsidies and high tariffs. The issue has been festering in the trade negotiating world for at least 30 years...but only since 1999 has it become clear that big third world food producers are willing to block everything until the rich countries liberalize their food markets.

The silly thing is that food makes up a small and shrinking portion of world trade. Think about globalization and you think computers! Biotech! Information technology! New, shiny things made in fancy factories and flown all around the world. Not a sack of potatoes! Alas...the sack of potatoes is what the negotiations are about.

What's clear is that farmers worldwide are incredibly powerful in their own countries. Coming into the conference I'd assumed that countries that import most of their food would not be particularly interested in being allowed to continue agricultural subsidies. Wrong! This morning I went to a press conference by the G10 group of net-food importing countries. The Mauritius trade minister made an impassioned speech against moves to liberalize the sugar market, describing the role of sugar cane farming in traditional society. This is Mauritius we're talking about, a bunch of tiny islands in the middle of the Indian Ocean that imports virtually all its food...even their delegation is basically held hostage by the farm lobby. The Norwegian and Swiss delegates made similar arguments about dairy farming.

The funny thing is that, in the end, all countries take more or less the same position on farm talks: lets liberalize everything...except my traditional sector! It's a sort of twist on NIMBYism...Not in My Traditional sector! Of course, every agricultural market is a market in the product of someone's traditional sector, and ministers are amazingly touchy on proposals that threaten their ability to protect their traditional producers. Not surprisingly, the overall result of so much aggregated touchiness is inaction.

How did it come to this? I think the reason is that agriculture has always been the most difficult issue, and since the Tokyo Round, back in the 70s, negotiators have been avoiding it. For thirty years now, serious negotiations on liberalizing agriculture have always run into major trouble, and the fall-back position has always been "well, farm issues are hard, so lets set them aside for now and concentrate on issues we can agree on."

The problem is that, by now, they've dealt with the whole rest of the agenda! Manufacturing tariffs are low worldwide, anti-subsidy and anti-dumping agreements are well developed, Intellectual Property Rights has its own side agreement, even Investment Measures proved easier to negotiate. There are still negotiations on each of those issues, but clearly those markets are nowhere near as distorted as farm trade. When it comes to major liberalization opportunities, agriculture is all that's left - and the mismatch between the general liberalism in most markets and the massive distortions still in place in farm trade are increasingly glaring. But every delegation here seems to be totally under the foot of its domestic farm lobby...so nobody here seems to think the meeting is going to succeed...

It's really strange...we're here in this super high-tech city, surrounded by ultramodern skyscrapers, chips, factories, computers, and you gather 149 of the most powerful people in the world to talk about the sparkling, gleaming hyperglobalized world economy of the 21st century and what do they talk about? They talk about Cain and Abel's profession! They talk about a business that's reached maturity roughly 3000 years ago!

The whole organization has been stuck on the agriculture issue for years. Big agricultural producers in the third world want much better access to first world markets - particularly Europe and Japan. Europe, Japan, and to a lesser extent the US want to continue protecting their farmers with subsidies and high tariffs. The issue has been festering in the trade negotiating world for at least 30 years...but only since 1999 has it become clear that big third world food producers are willing to block everything until the rich countries liberalize their food markets.

The silly thing is that food makes up a small and shrinking portion of world trade. Think about globalization and you think computers! Biotech! Information technology! New, shiny things made in fancy factories and flown all around the world. Not a sack of potatoes! Alas...the sack of potatoes is what the negotiations are about.

What's clear is that farmers worldwide are incredibly powerful in their own countries. Coming into the conference I'd assumed that countries that import most of their food would not be particularly interested in being allowed to continue agricultural subsidies. Wrong! This morning I went to a press conference by the G10 group of net-food importing countries. The Mauritius trade minister made an impassioned speech against moves to liberalize the sugar market, describing the role of sugar cane farming in traditional society. This is Mauritius we're talking about, a bunch of tiny islands in the middle of the Indian Ocean that imports virtually all its food...even their delegation is basically held hostage by the farm lobby. The Norwegian and Swiss delegates made similar arguments about dairy farming.

The funny thing is that, in the end, all countries take more or less the same position on farm talks: lets liberalize everything...except my traditional sector! It's a sort of twist on NIMBYism...Not in My Traditional sector! Of course, every agricultural market is a market in the product of someone's traditional sector, and ministers are amazingly touchy on proposals that threaten their ability to protect their traditional producers. Not surprisingly, the overall result of so much aggregated touchiness is inaction.

How did it come to this? I think the reason is that agriculture has always been the most difficult issue, and since the Tokyo Round, back in the 70s, negotiators have been avoiding it. For thirty years now, serious negotiations on liberalizing agriculture have always run into major trouble, and the fall-back position has always been "well, farm issues are hard, so lets set them aside for now and concentrate on issues we can agree on."

The problem is that, by now, they've dealt with the whole rest of the agenda! Manufacturing tariffs are low worldwide, anti-subsidy and anti-dumping agreements are well developed, Intellectual Property Rights has its own side agreement, even Investment Measures proved easier to negotiate. There are still negotiations on each of those issues, but clearly those markets are nowhere near as distorted as farm trade. When it comes to major liberalization opportunities, agriculture is all that's left - and the mismatch between the general liberalism in most markets and the massive distortions still in place in farm trade are increasingly glaring. But every delegation here seems to be totally under the foot of its domestic farm lobby...so nobody here seems to think the meeting is going to succeed...

Is that fear I smell?

In my first ghost blogger collaboration in a long time, I thought I'd keep it short and sweet:

Is it just me, or has the abstention (admittedly as high as 75%, although final numbers have yet to be released) really scared chavismo shitless?

Hugo was nowhere to be found for a couple of days after the election, same as every time he is facing a reversal of fortune. Then he pops up in Montevideo for the Mercosur thing, and again BAAAM canceled "Aló Delincuente".

And then today, this?

Exactly how scared is he by what happened, and how far is he willing to go to discredit any hint of criticism? Weren't PSF's and chavistas everywhere using this same report Chávez is in arms about to prove how free and how fair elections were?

Silbando en la oscuridad para espantar el miedo, dicen por ahí, huyendo hacia adelante.

Is it just me, or has the abstention (admittedly as high as 75%, although final numbers have yet to be released) really scared chavismo shitless?

Hugo was nowhere to be found for a couple of days after the election, same as every time he is facing a reversal of fortune. Then he pops up in Montevideo for the Mercosur thing, and again BAAAM canceled "Aló Delincuente".

And then today, this?

Exactly how scared is he by what happened, and how far is he willing to go to discredit any hint of criticism? Weren't PSF's and chavistas everywhere using this same report Chávez is in arms about to prove how free and how fair elections were?

Silbando en la oscuridad para espantar el miedo, dicen por ahí, huyendo hacia adelante.

December 12, 2005

Chilean elections, or a contrast in style

(My apologies to Quico for this CNE-related guest post...)

Chile held Presidential and Parliamentary elections this Sunday, and I wanted to take the opportunity to highlight differences with our current Venezuelan system which, quite frankly, leaves the chavista-led CNE without many arguments.

I don't want to dwell on the results (check Chilean newspapers like El Mercurio or La Tercera), but I can't continue without saying that, while the Parliamentary elections gave a big win to outgoing (and very popular) Pres. Ricardo Lagos' ruling coalition in both chambers, there will be a Presidential runoff in January. This election will be quite an anomaly for Latin-American politics, pitting the front-runner, Michelle Bachelet, a member of the not-so-Socialist Party, an agnostic, single mother and former victim of human rights abuses (and a woman, in case you're wondering), against center-right businessman and former Senator Sebastián Piñera, owner of a big chunk of LAN Airlines and TV station Chilevisión. What makes this election curious is that it pits two types of politicians that have made inroads the world over but had yet to make an appearance in LatAm politics in quite this way: a woman and a self-made billionaire.

But I digress. What is interesting about these elections for Venezuela is the process itself.

1. In Chile, everyone voted with a pen and a piece of paper, deposited their ballots in glass urns, and in the end, all votes were counted. If you believe Chávez and the CNE, you would think that this means that elections in Chile are rigged, that ballot-stuffing is common and that the system has all the problems the old system in Venezuela allegedy had. Think again. So far, there is not a single credible claim of fraud presented. The vote count was done in public, in front of numerous witnesses from all sides, with minimal interference from the Armed Forces and it was even televised nationally before the government announced any results. In other words, Chilean media was not submitted to any gag rule and the actual vote counting was broadcast to the entire country. (Granted, it made for boring TV since they could only transmit one voting table at a time, with zero representativeness).

The ballots themselves were quite simple and austere. It listed the names of all the candidates in an order that was previously determined by a public random draw. All the voter had to do was scratch a vertical line next to their candidate's horizontal line. Ballots themselves were small and understandable.

2. Final results were given by 11:30 PM. Given the complexity of this election, in which 120 deputies, 20 Senators and a President were selected, you would think the results would have taken days to come in. I mean, if the CNE, with the super-high-tech Jorge Rodríguez and the Tramparent Francisco Carrasquero could not give partial results until 5 am for a simple referendum in which the only options were "yes" and "no", surely Chileans would be counting votes until March. Not the case. As soon as tables were done with their tallying, which by the way began at 5 pm (no suspicious extension of the voting schedule to benefit government candidates like in Venezuela), they transmitted their results to the central government who then performed a simple duty: counting the results and announcing them to the country promptly.

Compare that to Venezuela, where in spite of having spent tens of millions of dollars on machines that few people believe in and even fewer know how to operate, the official tally of "results" takes several days to come in and the audit of 129 boxes takes up to a week to do.

This is important because one of the reasons the CNE argues that machines cannot be done away with is that this is the only way results can be given in time. Yet the Chilean experience proves this is not the case. But, it your intent is to cheat and/or you're incompetent, both qualities in abundance with our current CNE board, then you probably need some sort of gadget to fall back on.

3. All voters used their identity cards, which were created using a high-technology system that everyone trusts. Contrary to the quasi-rudimentary voting process, ID cards in Chile incorporate the latest technology to ensure nobody has duplicate ID cards and that voter rolls are not misteriously altered or sold on the streets. Aside from that, it takes three weeks to get your ID card and you can obtain one (providied you meet all requisites) in more than 300 offices nation-wide. Although there were problems with voters not appearing in actual rolls, none of them were significant enough to merit cries of fraud from anyone participating.

Contrast that with Venezuela, where ID cards are handed out without a proper backup of documentation, mysterious voter registration is commonplace and clandestine Colombian irregulars are free to vote at will. Every year, government after government promises to fix the Identification procedure to make it transparent, safe and quick, and every year we continue to have the worst ID system in the continent. The Chávez administration, for example, has created something called "Misión Identidad" which literally means issuing ID cards, Venezuelan nationalities and voter registration from the back of a pickup truck in selected spots that shift around from day to day (provided, of course, that you did not sign for recalling Chávez, in which case you get nothing).

4. The participation of the government, as well as candidate's advertisements, are strictly monitored. When Pres. Ricardo Lagos went to vote yesterday, he did not say who he wanted people to vote for. He basically said this was a great democratic feast in which everyone was free to express their opinion. In fact, the only times the President ventured into the electoral debate, he was sharply criticized. Basically, he took an institutional pose, not a blatantly propagandistic one like Mr. Chávez.

Advertisement only began in earnest a couple of months ago, but it had practically disappeared last Friday, in accordance with the law. Political parties were alloted free air time on TV every day to transmit their messages, but aside from that most publicity was in the form of signs out in the streets and paid advertisement in newspapers. In fact, even Chilevisión, Piñera´s TV station, was remarkably impartial during the campaign. (Note: Piñera has vowed to sell all of his holding, including LAN and Chilevisión, if he is elected. Take that, Berlusconi).

Contrast that with Venezuela, where... well, this is so obvious, I will not even expand on it.

What the Chilean process proves is that a Latin American democracy can thrive without needing to resort to highly-questionable high-tech voting gadgets, shabby ID systems, delayed announcements of results that create unnecessary tension or blatant use of government funds for the promotion of a single option. The current system espoused by the CNE is not credible for a large chunk of the population and does not even protect the secrecy of the vote, as has been correctly pointed out by international observers, and yet none of the excuses provided by the CNE to maintain its existence are necessary. The system is broken, and it has to go if we are ever to have fair elections again.

Chile held Presidential and Parliamentary elections this Sunday, and I wanted to take the opportunity to highlight differences with our current Venezuelan system which, quite frankly, leaves the chavista-led CNE without many arguments.

I don't want to dwell on the results (check Chilean newspapers like El Mercurio or La Tercera), but I can't continue without saying that, while the Parliamentary elections gave a big win to outgoing (and very popular) Pres. Ricardo Lagos' ruling coalition in both chambers, there will be a Presidential runoff in January. This election will be quite an anomaly for Latin-American politics, pitting the front-runner, Michelle Bachelet, a member of the not-so-Socialist Party, an agnostic, single mother and former victim of human rights abuses (and a woman, in case you're wondering), against center-right businessman and former Senator Sebastián Piñera, owner of a big chunk of LAN Airlines and TV station Chilevisión. What makes this election curious is that it pits two types of politicians that have made inroads the world over but had yet to make an appearance in LatAm politics in quite this way: a woman and a self-made billionaire.

But I digress. What is interesting about these elections for Venezuela is the process itself.

1. In Chile, everyone voted with a pen and a piece of paper, deposited their ballots in glass urns, and in the end, all votes were counted. If you believe Chávez and the CNE, you would think that this means that elections in Chile are rigged, that ballot-stuffing is common and that the system has all the problems the old system in Venezuela allegedy had. Think again. So far, there is not a single credible claim of fraud presented. The vote count was done in public, in front of numerous witnesses from all sides, with minimal interference from the Armed Forces and it was even televised nationally before the government announced any results. In other words, Chilean media was not submitted to any gag rule and the actual vote counting was broadcast to the entire country. (Granted, it made for boring TV since they could only transmit one voting table at a time, with zero representativeness).

The ballots themselves were quite simple and austere. It listed the names of all the candidates in an order that was previously determined by a public random draw. All the voter had to do was scratch a vertical line next to their candidate's horizontal line. Ballots themselves were small and understandable.

2. Final results were given by 11:30 PM. Given the complexity of this election, in which 120 deputies, 20 Senators and a President were selected, you would think the results would have taken days to come in. I mean, if the CNE, with the super-high-tech Jorge Rodríguez and the Tramparent Francisco Carrasquero could not give partial results until 5 am for a simple referendum in which the only options were "yes" and "no", surely Chileans would be counting votes until March. Not the case. As soon as tables were done with their tallying, which by the way began at 5 pm (no suspicious extension of the voting schedule to benefit government candidates like in Venezuela), they transmitted their results to the central government who then performed a simple duty: counting the results and announcing them to the country promptly.

Compare that to Venezuela, where in spite of having spent tens of millions of dollars on machines that few people believe in and even fewer know how to operate, the official tally of "results" takes several days to come in and the audit of 129 boxes takes up to a week to do.

This is important because one of the reasons the CNE argues that machines cannot be done away with is that this is the only way results can be given in time. Yet the Chilean experience proves this is not the case. But, it your intent is to cheat and/or you're incompetent, both qualities in abundance with our current CNE board, then you probably need some sort of gadget to fall back on.

3. All voters used their identity cards, which were created using a high-technology system that everyone trusts. Contrary to the quasi-rudimentary voting process, ID cards in Chile incorporate the latest technology to ensure nobody has duplicate ID cards and that voter rolls are not misteriously altered or sold on the streets. Aside from that, it takes three weeks to get your ID card and you can obtain one (providied you meet all requisites) in more than 300 offices nation-wide. Although there were problems with voters not appearing in actual rolls, none of them were significant enough to merit cries of fraud from anyone participating.

Contrast that with Venezuela, where ID cards are handed out without a proper backup of documentation, mysterious voter registration is commonplace and clandestine Colombian irregulars are free to vote at will. Every year, government after government promises to fix the Identification procedure to make it transparent, safe and quick, and every year we continue to have the worst ID system in the continent. The Chávez administration, for example, has created something called "Misión Identidad" which literally means issuing ID cards, Venezuelan nationalities and voter registration from the back of a pickup truck in selected spots that shift around from day to day (provided, of course, that you did not sign for recalling Chávez, in which case you get nothing).

4. The participation of the government, as well as candidate's advertisements, are strictly monitored. When Pres. Ricardo Lagos went to vote yesterday, he did not say who he wanted people to vote for. He basically said this was a great democratic feast in which everyone was free to express their opinion. In fact, the only times the President ventured into the electoral debate, he was sharply criticized. Basically, he took an institutional pose, not a blatantly propagandistic one like Mr. Chávez.

Advertisement only began in earnest a couple of months ago, but it had practically disappeared last Friday, in accordance with the law. Political parties were alloted free air time on TV every day to transmit their messages, but aside from that most publicity was in the form of signs out in the streets and paid advertisement in newspapers. In fact, even Chilevisión, Piñera´s TV station, was remarkably impartial during the campaign. (Note: Piñera has vowed to sell all of his holding, including LAN and Chilevisión, if he is elected. Take that, Berlusconi).

Contrast that with Venezuela, where... well, this is so obvious, I will not even expand on it.

What the Chilean process proves is that a Latin American democracy can thrive without needing to resort to highly-questionable high-tech voting gadgets, shabby ID systems, delayed announcements of results that create unnecessary tension or blatant use of government funds for the promotion of a single option. The current system espoused by the CNE is not credible for a large chunk of the population and does not even protect the secrecy of the vote, as has been correctly pointed out by international observers, and yet none of the excuses provided by the CNE to maintain its existence are necessary. The system is broken, and it has to go if we are ever to have fair elections again.

December 10, 2005

Savage Neoliberalism Chronicles

Folks, for the next nine days I'm going to be away from the blog - tomorrow I fly off to the one shindig PSF's love to hate the most: the WTO Ministerial Conference in Hong Kong. I'll be covering it for VenEconomía, and doing some networking for my dissertation research.

I'm actually really looking forward to it. Oh to be at the epicenter of the world economy! A WTO Ministerial is a trade policy researcher's shangri-la. 148 ministers along with their delegations and thousands upon thousands of lobbyists, journalists and NGOs...everyone who is anyone in trade politics all in one place at one time. Lemme tell you it was a MESS trying to get a hotel room!

But never fear: Pepe Mora and Katy have agreed to ghost blog while I'm away. Now, you two...don't blog anything I wouldn't blog...

I'm actually really looking forward to it. Oh to be at the epicenter of the world economy! A WTO Ministerial is a trade policy researcher's shangri-la. 148 ministers along with their delegations and thousands upon thousands of lobbyists, journalists and NGOs...everyone who is anyone in trade politics all in one place at one time. Lemme tell you it was a MESS trying to get a hotel room!

But never fear: Pepe Mora and Katy have agreed to ghost blog while I'm away. Now, you two...don't blog anything I wouldn't blog...

December 9, 2005

Just Priceless

Chavista Trade Policy: Something for nothing...

I can't say I really get it. Not two months ago Chavez was denouncing Mercosur as a "failed neoliberal experiment" and now we're about to join it. Though I know most of you don't believe it, I really am working on a PhD dissertation on trade policy in between breaks from blogging, so this is one issue I can claim expertise on.

Conventional economic theory tells us two basic things about what happens when you liberalize imports. First: the economy as a whole is made better off. Second, the gains are not evenly distributed. While everyone is made a little bit better off, some are made much worse off.

To see why, take a simple example. Say our farmers can produce corn for 100 per kilo. Foreign farmers can produce it for 95. When you liberalize imports, the price of corn to our consumers drops, so everyone is made a little bit better off. At the same time, our corn farmers suddenly find they can't compete, so they're wiped out of the market.

In the lingo, gains from import liberalization are diffuse, but costs are concentrated.

This explains why countries rarely liberalize unilaterally even if economic theory shows that the diffuse gains are bigger than the concentrated losses. Governments, in general, pay more attention to organized groups that mobilize to lobby for a given policy than they do to calculations of overall welfare or economics textbooks. Since each consumer is made only a little bit better off by import liberalization, consumers as a group find it difficult to organize themselves to petition the government for liberalization. But since producers stand to lose a lot, they have a much easier time banding together to lobby for protection.

Of course, that tells only half the story, because countries also have sectors that stand to gain from trade. If, say, our producers can make neckties for 95 a kilo, but it costs their producers 100 to produce that many neckties, our necktie producers obviously stand to gain a lot from access to their market. Liberalization would make neckties slightly more expensive in our country, but the costs to our necktie consumers are diffuse, while the gains to our necktie producers are concentrated. The equation is exactly reversed.

In that case, our necktie producers have every incentive to lobby our government for better access to their market. But when our government sits down to ask their government to open up their necktie market, it has to offer something in return. Since their corn producers are interested in better access to our corn market, there's a fairly obvious bargain to be struck: we'll liberalize our corn market if you'll liberalize your tie market. This, in extreme shorthand, is the reason trade negotiations happen.

The whole point of trade negotiations, then, is to overcome a problem of collective action by making sure someone in our country has a strong interest in seeing our own markets liberalized. If our government tries to liberalize corn unilaterally, corn farmers will work hard to block it, and there'll be no other group similarly organized to argue in favor of liberalization. By bargaining off access to our corn market against access to their tie market, trade negotiations set up a situation where our tie producers have a strong incentive to push our government to liberalize our corn market - as an indirect way of gaining access to their tie market. It's a pretty nifty trick.

This little framework is enough to explain why Chavez's decision to join Mercosur is puzzling to say the least. In effect, Venezuela will be opening up its market to Argentina and Brazil's world-beating agricultural producers. Not surprisingly, Venezuela's agricultural producers are none too happy about this. Venezuelan manufacturers are similarly freaked out. In exchange for their sacrifice, though, we'll get access to...um...to...what precisely? Venezuela's major export commodity is oil, but we already have free access to their energy markets! If there is some Venezuelan export sector chomping at the bit for better access to Southern Cone markets, I haven't heard about it. So, in effect, Chavez proposes to give them access to our farm market in exchange for...nothing!

It's true that there are a number of sectors where Venezuela has a potential comparative advantage, and joining mercosur provides new opportunities for those sectors. However, a pile of economic research - most of it from left-leaning academics - argues convincingly that better access to foreign markets is very rarely enough to turn potential comparative into actual export success. To do that, you need a whole raft of government measures - from R&D tax credits and export credit to specialized training institutes and improved property rights - to help boost domestic producers' competitiveness to the point where they actually can crack foreign markets. Needless to say, those supply-side policies are not in place in the Bolivarian revolution.