Folks, for the next nine days I'm going to be away from the blog - tomorrow I fly off to the one shindig PSF's love to hate the most: the WTO Ministerial Conference in Hong Kong. I'll be covering it for VenEconomía, and doing some networking for my dissertation research.

I'm actually really looking forward to it. Oh to be at the epicenter of the world economy! A WTO Ministerial is a trade policy researcher's shangri-la. 148 ministers along with their delegations and thousands upon thousands of lobbyists, journalists and NGOs...everyone who is anyone in trade politics all in one place at one time. Lemme tell you it was a MESS trying to get a hotel room!

But never fear: Pepe Mora and Katy have agreed to ghost blog while I'm away. Now, you two...don't blog anything I wouldn't blog...

December 10, 2005

December 9, 2005

Just Priceless

Chavista Trade Policy: Something for nothing...

I can't say I really get it. Not two months ago Chavez was denouncing Mercosur as a "failed neoliberal experiment" and now we're about to join it. Though I know most of you don't believe it, I really am working on a PhD dissertation on trade policy in between breaks from blogging, so this is one issue I can claim expertise on.

Conventional economic theory tells us two basic things about what happens when you liberalize imports. First: the economy as a whole is made better off. Second, the gains are not evenly distributed. While everyone is made a little bit better off, some are made much worse off.

To see why, take a simple example. Say our farmers can produce corn for 100 per kilo. Foreign farmers can produce it for 95. When you liberalize imports, the price of corn to our consumers drops, so everyone is made a little bit better off. At the same time, our corn farmers suddenly find they can't compete, so they're wiped out of the market.

In the lingo, gains from import liberalization are diffuse, but costs are concentrated.

This explains why countries rarely liberalize unilaterally even if economic theory shows that the diffuse gains are bigger than the concentrated losses. Governments, in general, pay more attention to organized groups that mobilize to lobby for a given policy than they do to calculations of overall welfare or economics textbooks. Since each consumer is made only a little bit better off by import liberalization, consumers as a group find it difficult to organize themselves to petition the government for liberalization. But since producers stand to lose a lot, they have a much easier time banding together to lobby for protection.

Of course, that tells only half the story, because countries also have sectors that stand to gain from trade. If, say, our producers can make neckties for 95 a kilo, but it costs their producers 100 to produce that many neckties, our necktie producers obviously stand to gain a lot from access to their market. Liberalization would make neckties slightly more expensive in our country, but the costs to our necktie consumers are diffuse, while the gains to our necktie producers are concentrated. The equation is exactly reversed.

In that case, our necktie producers have every incentive to lobby our government for better access to their market. But when our government sits down to ask their government to open up their necktie market, it has to offer something in return. Since their corn producers are interested in better access to our corn market, there's a fairly obvious bargain to be struck: we'll liberalize our corn market if you'll liberalize your tie market. This, in extreme shorthand, is the reason trade negotiations happen.

The whole point of trade negotiations, then, is to overcome a problem of collective action by making sure someone in our country has a strong interest in seeing our own markets liberalized. If our government tries to liberalize corn unilaterally, corn farmers will work hard to block it, and there'll be no other group similarly organized to argue in favor of liberalization. By bargaining off access to our corn market against access to their tie market, trade negotiations set up a situation where our tie producers have a strong incentive to push our government to liberalize our corn market - as an indirect way of gaining access to their tie market. It's a pretty nifty trick.

This little framework is enough to explain why Chavez's decision to join Mercosur is puzzling to say the least. In effect, Venezuela will be opening up its market to Argentina and Brazil's world-beating agricultural producers. Not surprisingly, Venezuela's agricultural producers are none too happy about this. Venezuelan manufacturers are similarly freaked out. In exchange for their sacrifice, though, we'll get access to...um...to...what precisely? Venezuela's major export commodity is oil, but we already have free access to their energy markets! If there is some Venezuelan export sector chomping at the bit for better access to Southern Cone markets, I haven't heard about it. So, in effect, Chavez proposes to give them access to our farm market in exchange for...nothing!

It's true that there are a number of sectors where Venezuela has a potential comparative advantage, and joining mercosur provides new opportunities for those sectors. However, a pile of economic research - most of it from left-leaning academics - argues convincingly that better access to foreign markets is very rarely enough to turn potential comparative into actual export success. To do that, you need a whole raft of government measures - from R&D tax credits and export credit to specialized training institutes and improved property rights - to help boost domestic producers' competitiveness to the point where they actually can crack foreign markets. Needless to say, those supply-side policies are not in place in the Bolivarian revolution.

In practical terms from Venezuela's point of view, joining Mercosur is a lot like liberalizing our imports unilaterally. Now, there's an old and venerable economic argument in favor of unilateral liberalization. I'm not going to get into that debate here, but I will point out that it's an argument one associates more with Adam Smith, Milton Friedman and Jagdish Baghwati than with Ezequiel Zamora, Jorge Giordani, or Martha Harnecker. How, exactly, the decision to enter Mercosur fits in with Chavez's whole verbal diarrhea about food security, endogenous development, land reform, etc. etc. I haven't the slightest clue. It's more like neoliberalismo del siglo 21, really...

Conventional economic theory tells us two basic things about what happens when you liberalize imports. First: the economy as a whole is made better off. Second, the gains are not evenly distributed. While everyone is made a little bit better off, some are made much worse off.

To see why, take a simple example. Say our farmers can produce corn for 100 per kilo. Foreign farmers can produce it for 95. When you liberalize imports, the price of corn to our consumers drops, so everyone is made a little bit better off. At the same time, our corn farmers suddenly find they can't compete, so they're wiped out of the market.

In the lingo, gains from import liberalization are diffuse, but costs are concentrated.

This explains why countries rarely liberalize unilaterally even if economic theory shows that the diffuse gains are bigger than the concentrated losses. Governments, in general, pay more attention to organized groups that mobilize to lobby for a given policy than they do to calculations of overall welfare or economics textbooks. Since each consumer is made only a little bit better off by import liberalization, consumers as a group find it difficult to organize themselves to petition the government for liberalization. But since producers stand to lose a lot, they have a much easier time banding together to lobby for protection.

Of course, that tells only half the story, because countries also have sectors that stand to gain from trade. If, say, our producers can make neckties for 95 a kilo, but it costs their producers 100 to produce that many neckties, our necktie producers obviously stand to gain a lot from access to their market. Liberalization would make neckties slightly more expensive in our country, but the costs to our necktie consumers are diffuse, while the gains to our necktie producers are concentrated. The equation is exactly reversed.

In that case, our necktie producers have every incentive to lobby our government for better access to their market. But when our government sits down to ask their government to open up their necktie market, it has to offer something in return. Since their corn producers are interested in better access to our corn market, there's a fairly obvious bargain to be struck: we'll liberalize our corn market if you'll liberalize your tie market. This, in extreme shorthand, is the reason trade negotiations happen.

The whole point of trade negotiations, then, is to overcome a problem of collective action by making sure someone in our country has a strong interest in seeing our own markets liberalized. If our government tries to liberalize corn unilaterally, corn farmers will work hard to block it, and there'll be no other group similarly organized to argue in favor of liberalization. By bargaining off access to our corn market against access to their tie market, trade negotiations set up a situation where our tie producers have a strong incentive to push our government to liberalize our corn market - as an indirect way of gaining access to their tie market. It's a pretty nifty trick.

This little framework is enough to explain why Chavez's decision to join Mercosur is puzzling to say the least. In effect, Venezuela will be opening up its market to Argentina and Brazil's world-beating agricultural producers. Not surprisingly, Venezuela's agricultural producers are none too happy about this. Venezuelan manufacturers are similarly freaked out. In exchange for their sacrifice, though, we'll get access to...um...to...what precisely? Venezuela's major export commodity is oil, but we already have free access to their energy markets! If there is some Venezuelan export sector chomping at the bit for better access to Southern Cone markets, I haven't heard about it. So, in effect, Chavez proposes to give them access to our farm market in exchange for...nothing!

It's true that there are a number of sectors where Venezuela has a potential comparative advantage, and joining mercosur provides new opportunities for those sectors. However, a pile of economic research - most of it from left-leaning academics - argues convincingly that better access to foreign markets is very rarely enough to turn potential comparative into actual export success. To do that, you need a whole raft of government measures - from R&D tax credits and export credit to specialized training institutes and improved property rights - to help boost domestic producers' competitiveness to the point where they actually can crack foreign markets. Needless to say, those supply-side policies are not in place in the Bolivarian revolution.

In practical terms from Venezuela's point of view, joining Mercosur is a lot like liberalizing our imports unilaterally. Now, there's an old and venerable economic argument in favor of unilateral liberalization. I'm not going to get into that debate here, but I will point out that it's an argument one associates more with Adam Smith, Milton Friedman and Jagdish Baghwati than with Ezequiel Zamora, Jorge Giordani, or Martha Harnecker. How, exactly, the decision to enter Mercosur fits in with Chavez's whole verbal diarrhea about food security, endogenous development, land reform, etc. etc. I haven't the slightest clue. It's more like neoliberalismo del siglo 21, really...

December 8, 2005

That Useless Election for the Red Caudillo

By Guido Rampoldi in La Repubblica

Translated by me

This article caught my eye for several reasons. For one thing, it's rare to see foreign journalists grasp how hollow Chavez's claim to be leading a revolution really is, and Rampoldi is unsparing on that point. For another, it's always significant when a left-wing paper turns on Chavez, and this piece appeared in La Repubblica, which is sort of like the Italian version of The Guardian.

The hot gift in Caracas this Christmas is the chavito, an action figure depicting Hugo Chavez in his movement's red uniform. The buyers are both those who love the president, who buy it so their kids will also learn to love him, and those who hate him, who buy it perhaps to skewer it with needles. Saturday night, on the eve of the parliamentary election, an entertainer on State TV showed the cameras two chavitos, and said "tomorrow, you can vote either for this one or this one" to laughter from the chavista candidates around him. They chatted about the opposition - all of it "coup-mongering and fascist," and, why not, anti-patriotic - and later about the empire, imperialism, in short, the US, the opposition's alleged benefactors. Then we saw video links from various rallies, with fireworks, patriotic and revolutionary songs and people in red shirts chanting: fascists, golpistas, imperialists, enemies of the people. Finally Chavez himself turned up, reciting a poem along with a guitar player. Then it was back to the studio, and the chants again: fasicsts, golpistas, imperialists.

Seeing all this, just hours before the start of voting, you had the impression they had just defrosted that South American left that never learned anything from its own mistakes. Tenacious, unhinged, incorregible.

Add to that the fact that in Washington you have the Bush administration and that the Venezuelan opposition is remarkably dim, and it's not hard to imagine where the sum of so much ineptitude was going to lead: to the Nth disaster.

Sunday's parliamentary elections were certainly a step in that direction. The biggest Opposition parties decided to boycot them when they discovered the electronic voting system made it possible to identify voter's choices. But a technical compromise was possible, and the choice to abandon the elections was determined by fear. They were headed for a humiliating defeat, according both to the polls and to the state of mind of an antichavista electorate that believes neither in the deformed democracy you see on state-TV nor in an Opposition lacking a coherent identity.

So Chavez will no longer be restrained by parliament. Up to now, his partisans had enough votes to govern, but not to change the constitution. After Sunday, he'll be able to get his way on the most far-fetched of projects, even becoming president for life as one of his parliamentarians has proposed. Worse yet, with the Opposition absent from parliament, the country now lacks the only institution that might mediate the conflict between two Venezuelas unable to build a single national community and convinced that the other side is a tool of foreign interests: of Cuba, or of the United States.

When you ask the red shirts how Chavez's six years in power have changed their lives, they speak first of Mercal. These are stores in poor neighborhoods where anyone can buy, at political prices, food imported by the government...with the following results: the poor finally eat top grade Argentine and Uruguayan beef, the rich pay half as much as they used to (since access to Mercal is open to all), and Venezuelan ranchers are in crisis.

In the ranking of gratitudes, after Mercal you hear about health care, which has been overhauled thanks to a massive influx of Cuban doctors, and later about schools where adults learn to read and write or get training for a job. Moreover, Chavez has given a small push to programs for refurbishing poor neighborhoods - which, however, were started decades earlier - and has restarted land reform, though not truly aggressively.

According to the propaganda, this would amount to Bolivarian Socialism, a new, revolutionary economic model. But if that's case, we would also have to consider Italy's Christian Democrats to be Bolivarian Socialists, for everything they did in the 20 years after the war, and using the same method as Chavez: privileging first and foremost their own electorate.

The fact is that it's easy to be bolivarian towards your own supporters when you govern the world's fifth oil exporter at a time when oil is above $50 a barrel. Probably, the old social democrats and christian democrats who used to rule the country would have been just as generous: the crisis that brought them down reached its peak in the late 90s, when oil sunk to $9 per barrel.

What would have made a real difference would have been deep structural reforms, especially in the public administration. Yet even chavistas admit that the public administration has not changed.

For instance, those sections of the police widely feared for their rapacity and violence. Hundreds of complaints accuse them of fighting crime with torture and premeditated murders.

This happened in the past also. But today, the atmosphere is even more favorable to such abuses. After all, a former member of the Caracas police special forces - in fact, death squads - is a chavista mayor of a part of Caracas and uses "we will take back the city" as a slogan - you can read it painted on walls just steps from the presidential palace.

The opposition didn't much care about this variable-geometry legality until it realized it was tremendously exposed. The chavistas have taken control of the Supreme Court boosting its membership from 20 to 32, and the chief judge qualifies as "revolutionary" the justice it imparts. The number of judges with temporary appointments has grown to a full 75% of the total, keeping them nice and tame.

Made public by a pro-government web site, the list of the 3 and a half million Venezuelans who signed the petitions for a referendum against Chavez has become a tool of political discriminition in the hands of the public administration. Through new laws, they've tamed the fury of the private TV stations, which until two years ago were arguably even worse than state TV, but are now either circumspect or indifferent (because they risk hyperbolic fines and shut downs.) They've also aimed straight at the journalists: they risk 30 month jail sentences if they criticize too strongly even a National Assembly member or a general, up to five years if they publish news that "disturb public order." In the new Penal Code, blocking a street can land you in jail from 4 to 8 years, and according to the Supreme Tribunal there is nothing illegal about prior censorship.

Until now, the government has resorted these pointed weapons only rarely.

But when the time comes, they'll be ready. In October, the Bush administration added Venezuela to the list of five enemies of the United States, even if it's on the third tier. In response, Chavez ordered his armed forces to prepare for "asymetrical warfare", to be taken to the enemy through "non-conventional tactics, such as guerrillas and terrorism." Whether or not he really believes in the prospect of a power play by Washington, trumpeting the possibility is extremely useful as a way to keep his country underfoot, and, in a few years time, to launch a more explicit authoritarianism: if the nation is under attack, who could protest if the president arrests the traitors, crushing the enemy's fifth column?

Translated by me

This article caught my eye for several reasons. For one thing, it's rare to see foreign journalists grasp how hollow Chavez's claim to be leading a revolution really is, and Rampoldi is unsparing on that point. For another, it's always significant when a left-wing paper turns on Chavez, and this piece appeared in La Repubblica, which is sort of like the Italian version of The Guardian.

The hot gift in Caracas this Christmas is the chavito, an action figure depicting Hugo Chavez in his movement's red uniform. The buyers are both those who love the president, who buy it so their kids will also learn to love him, and those who hate him, who buy it perhaps to skewer it with needles. Saturday night, on the eve of the parliamentary election, an entertainer on State TV showed the cameras two chavitos, and said "tomorrow, you can vote either for this one or this one" to laughter from the chavista candidates around him. They chatted about the opposition - all of it "coup-mongering and fascist," and, why not, anti-patriotic - and later about the empire, imperialism, in short, the US, the opposition's alleged benefactors. Then we saw video links from various rallies, with fireworks, patriotic and revolutionary songs and people in red shirts chanting: fascists, golpistas, imperialists, enemies of the people. Finally Chavez himself turned up, reciting a poem along with a guitar player. Then it was back to the studio, and the chants again: fasicsts, golpistas, imperialists.

Seeing all this, just hours before the start of voting, you had the impression they had just defrosted that South American left that never learned anything from its own mistakes. Tenacious, unhinged, incorregible.

Add to that the fact that in Washington you have the Bush administration and that the Venezuelan opposition is remarkably dim, and it's not hard to imagine where the sum of so much ineptitude was going to lead: to the Nth disaster.

Sunday's parliamentary elections were certainly a step in that direction. The biggest Opposition parties decided to boycot them when they discovered the electronic voting system made it possible to identify voter's choices. But a technical compromise was possible, and the choice to abandon the elections was determined by fear. They were headed for a humiliating defeat, according both to the polls and to the state of mind of an antichavista electorate that believes neither in the deformed democracy you see on state-TV nor in an Opposition lacking a coherent identity.

So Chavez will no longer be restrained by parliament. Up to now, his partisans had enough votes to govern, but not to change the constitution. After Sunday, he'll be able to get his way on the most far-fetched of projects, even becoming president for life as one of his parliamentarians has proposed. Worse yet, with the Opposition absent from parliament, the country now lacks the only institution that might mediate the conflict between two Venezuelas unable to build a single national community and convinced that the other side is a tool of foreign interests: of Cuba, or of the United States.

When you ask the red shirts how Chavez's six years in power have changed their lives, they speak first of Mercal. These are stores in poor neighborhoods where anyone can buy, at political prices, food imported by the government...with the following results: the poor finally eat top grade Argentine and Uruguayan beef, the rich pay half as much as they used to (since access to Mercal is open to all), and Venezuelan ranchers are in crisis.

In the ranking of gratitudes, after Mercal you hear about health care, which has been overhauled thanks to a massive influx of Cuban doctors, and later about schools where adults learn to read and write or get training for a job. Moreover, Chavez has given a small push to programs for refurbishing poor neighborhoods - which, however, were started decades earlier - and has restarted land reform, though not truly aggressively.

According to the propaganda, this would amount to Bolivarian Socialism, a new, revolutionary economic model. But if that's case, we would also have to consider Italy's Christian Democrats to be Bolivarian Socialists, for everything they did in the 20 years after the war, and using the same method as Chavez: privileging first and foremost their own electorate.

The fact is that it's easy to be bolivarian towards your own supporters when you govern the world's fifth oil exporter at a time when oil is above $50 a barrel. Probably, the old social democrats and christian democrats who used to rule the country would have been just as generous: the crisis that brought them down reached its peak in the late 90s, when oil sunk to $9 per barrel.

What would have made a real difference would have been deep structural reforms, especially in the public administration. Yet even chavistas admit that the public administration has not changed.

For instance, those sections of the police widely feared for their rapacity and violence. Hundreds of complaints accuse them of fighting crime with torture and premeditated murders.

This happened in the past also. But today, the atmosphere is even more favorable to such abuses. After all, a former member of the Caracas police special forces - in fact, death squads - is a chavista mayor of a part of Caracas and uses "we will take back the city" as a slogan - you can read it painted on walls just steps from the presidential palace.

The opposition didn't much care about this variable-geometry legality until it realized it was tremendously exposed. The chavistas have taken control of the Supreme Court boosting its membership from 20 to 32, and the chief judge qualifies as "revolutionary" the justice it imparts. The number of judges with temporary appointments has grown to a full 75% of the total, keeping them nice and tame.

Made public by a pro-government web site, the list of the 3 and a half million Venezuelans who signed the petitions for a referendum against Chavez has become a tool of political discriminition in the hands of the public administration. Through new laws, they've tamed the fury of the private TV stations, which until two years ago were arguably even worse than state TV, but are now either circumspect or indifferent (because they risk hyperbolic fines and shut downs.) They've also aimed straight at the journalists: they risk 30 month jail sentences if they criticize too strongly even a National Assembly member or a general, up to five years if they publish news that "disturb public order." In the new Penal Code, blocking a street can land you in jail from 4 to 8 years, and according to the Supreme Tribunal there is nothing illegal about prior censorship.

Until now, the government has resorted these pointed weapons only rarely.

But when the time comes, they'll be ready. In October, the Bush administration added Venezuela to the list of five enemies of the United States, even if it's on the third tier. In response, Chavez ordered his armed forces to prepare for "asymetrical warfare", to be taken to the enemy through "non-conventional tactics, such as guerrillas and terrorism." Whether or not he really believes in the prospect of a power play by Washington, trumpeting the possibility is extremely useful as a way to keep his country underfoot, and, in a few years time, to launch a more explicit authoritarianism: if the nation is under attack, who could protest if the president arrests the traitors, crushing the enemy's fifth column?

December 7, 2005

The EU Electoral Observation Mission's Preliminary Report

is here.

Key Findings:

Wide sectors of the Venezuelan society do not have trust in the electoral process and in the independence of the electoral authority.

The legal framework contains several inconsistencies that leave room for differing and contradictory interpretations.

The disclosure of a computerized list of citizens indicating their political preference in the signature recollection process for the Presidential Recall Referendum (so-called “Maisanta Program”) generates fear that the secrecy of the vote could be violated.

The CNE, in a positive attempt to restore confidence in the electoral process, took significant steps to open the automated voting system to external scrutiny and to modify various aspects that were questioned by the opposition.

The CNE decision to eliminate the fingerprint capturing devices from the voting process was timely, effective and constructive.

The electoral campaign focused almost exclusively on the issue of distrust in the electoral process and lack of independence of the CNE. The debate on political party platforms was absent.

Both State and private media monitored showed bias towards either of the two main political blocks.

The EU EOM took note with surprise of the withdrawal of the majority of the opposition parties only four days before the electoral event.

Election Day passed peacefully with a low turnout. While the observers noted several irregularities in the voting procedures, the manual audit of the voting receipts revealed a high reliability of the voting machines.

These elections did not contribute to the reduction of the fracture in the Venezuelan society. In this sense, they represented a lost opportunity.

This bit, in the inside pages, is just priceless:

Key Findings:

This bit, in the inside pages, is just priceless:

The use of the electoral technique known as Morochas, which allows the duplication of parties in order to avoid the subtraction of the seats gained in the plurality-majority list from the proportional list, certainly defies the spirit of the Constitution, but it is technically allowed by the mixed system of representation laid out in the Basic Law of Suffrage and Political Participation.So the morochas are legal but unconstitutional...WTF!?!??

JVR's Election

Another one for the Chavez-as-Pinky, JVR-as-The-Brain archive, this time from Phil Gunson's piece in the Miami Herald:

At times I really get the sense we underestimate JVR's role in Chavez's success. The guy is brutal but incredibly effective. The events of the last two weeks can be seen as a kind of monument to José Simiente's political instincts. Nobody on our side is anywhere near as macchiavelian or effective...

Western diplomats in Caracas meanwhile criticized what they said were last-minute changes to soften the wording of the OAS report -- and alleged that the changes were made under strong pressure from the Venezuelan government.

The Herald was told by diplomats from both EU and OAS member states that OAS observer mission chief Rubén Perina received calls from Venezuelan Vice President José Vicente Rangel and electoral council chairman Jorge Rodríguez after the draft report had already been prepared.

The OAS had planned to present its report at a news conference early Tuesday. But it canceled the conference at the last minute and the report was distributed on the Internet.

At times I really get the sense we underestimate JVR's role in Chavez's success. The guy is brutal but incredibly effective. The events of the last two weeks can be seen as a kind of monument to José Simiente's political instincts. Nobody on our side is anywhere near as macchiavelian or effective...

December 6, 2005

More on Dec. 4th as seen from abroad...

As we await the International Observers' preliminary reports on the December 4th vote (due out this afternoon), we can chew on some of the foreign media coverage of the election.

There's finally a bit of comfort for the opposition in this understatedly scathing article by Andy Webb-Vidal in the Financial Times:

But the extremely influential and unmistakably antichavista Economist runs a lead paragraph straight out of Jose Vicente Rangel's wet dreams

Meanwhile, Spain's El Pais runs a tough editorial criticizing the opposition withdrawal, but also blasting Chavez's antidemocratic tendencies. Opening graf:

There's finally a bit of comfort for the opposition in this understatedly scathing article by Andy Webb-Vidal in the Financial Times:

Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s president, on Monday awoke to hear the type of election result usually reserved for the most power-hungry of dictators: 100 per cent of the seats.

The unofficial result, from polls held on Sunday to select the composition of the single-chamber legislature, signals a victory of sorts for the militaristic, left-leaning ruler of the world’s fifth-largest oil exporter.

But critics said it was a hollow victory that left Venezuela in a twilight zone between democracy and dictatorship - and a result that would catapult the country towards Mr Chávez’s model of “21st century socialism”.

Preliminary results from the National Electoral Council (CNE), which on Monday was still calculating the final tally, showed that only 25 per cent of eligible voters cast ballots in polls boycotted by opponents. A fifth of ballots cast were blank.

But the extremely influential and unmistakably antichavista Economist runs a lead paragraph straight out of Jose Vicente Rangel's wet dreams

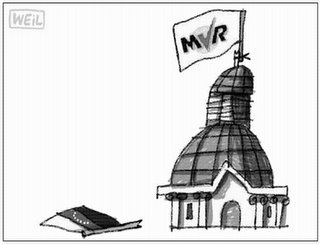

A FREE and fair election in which the president’s supporters win all of the seats in the legislature? It sounds more like the kind of contest Saddam Hussein used to “win” in Iraq with 99% of the vote. But on Sunday December 4th, the party of Venezuela’s president, Hugo Chávez, and groups close to him seem to have done just that, after all but one of the opposition parties pulled out of the election. Mr Chávez’s Fifth Republic Movement (MVR) won 114 seats out of 167. Allied parties took the rest.

Meanwhile, Spain's El Pais runs a tough editorial criticizing the opposition withdrawal, but also blasting Chavez's antidemocratic tendencies. Opening graf:

The Venezuelan Opposition has made a mistake in boycotting Sunday's legislative elections, overwhelmingly won by partisans of president Hugo Chavez. The formidable abstention, at 75%, undoubtedly undermines the representative nature of the new, monochrome National Assembly, but it does not invalidate its decisions. The basic result of the vote is that the opposition has ceased to exist in politically organized form. The parties opposed to Chavez - promised an unmitigated defeat by the polls - have taken cover behind the scarce credibility of the voting procedure and the unmistakable pro-government bias of the electoral authorities to justify their boycott. As we await preliminary reports from the international observers, nothing right now suggests serious irregularities.

Opinion Duel: Day Two

Well, Alek was pretty unsparing in his first post, so I went ahead and responded pretty strongly.

Though, we obviously don't agree on much, I've always appreciated Alek's willingness to engage in proper debate. We'll see what he writes back...

Though, we obviously don't agree on much, I've always appreciated Alek's willingness to engage in proper debate. We'll see what he writes back...

December 5, 2005

Second Venezuela Opinion Duel: Alek Boyd thinks I've lost my marbles

Well, the Second Venezuela Opinion Duel is under way. Alek Boyd sent his opening salvo a while back, but I hadn't responded pending the election.

I'm writing a reply now, I'll post it tomorrow.

I'm writing a reply now, I'll post it tomorrow.

Euphoria Unhinged

I'm not just trying to bolster my credentials as official Party Poop here, but the euphoria over at Daniel and Miguel's blogs, as well as other Oppo cyberspace hangouts, strikes me as really really bizarre. Maybe it's because I'm not in Caracas - or maybe it's because it's easier to keep perspective from a distance - but I can't for the life of me figure out what the Oppo has to celebrate.

First off, suggesting that 75% abstention means 75% of the voters support the Opposition is deeply, deeply silly. In the 2000 parliamentary elections - which would tend to have higher turnout anyway, because you were electing a president as well - abstention was 44%. Out of the 56% that did vote, a little over half voted for Chavez. Say 30% of the overall electorate.

So, frankly, I don't see how 25% turnout is a terrible result for the government. Of course, we can't be sure that figure wasn't "massaged" - because CNE steadfastly refused to hand-count all the ballots as Article 172 of LOSPP mandates. But assuming provisionally that that's the right figure, it's just a 5 percentage point drop from 2000. Actually, I'd say the government did pretty well to motivate that many people to vote, considering there was no real contest, and no presidential vote.

First off, suggesting that 75% abstention means 75% of the voters support the Opposition is deeply, deeply silly. In the 2000 parliamentary elections - which would tend to have higher turnout anyway, because you were electing a president as well - abstention was 44%. Out of the 56% that did vote, a little over half voted for Chavez. Say 30% of the overall electorate.

So, frankly, I don't see how 25% turnout is a terrible result for the government. Of course, we can't be sure that figure wasn't "massaged" - because CNE steadfastly refused to hand-count all the ballots as Article 172 of LOSPP mandates. But assuming provisionally that that's the right figure, it's just a 5 percentage point drop from 2000. Actually, I'd say the government did pretty well to motivate that many people to vote, considering there was no real contest, and no presidential vote.

The Day After

If you were hoping that high abstention would "delegitimate" the government internationally, today's foreign newspapers make for some depressing reading. Chavismo's lead in the polls is the key reason cited for the Opposition pullout. The general consensus is that, faced with the prospect of humiliating defeat, the Opposition withdrew in a childish hissy-fit. Our concerns about CNE partiality, illegality, etc. etc. are given passing mention in articles focusing on the Oppo harakiri. Whether professional diplomats and others paid to track these things more closely will come away with a different perception is an open question - but hyperbolic Oppo predictions that "the world will have to open its eyes to the real nature of the regime" will have been sorely disappointed.

This is really not so surprising, considering the polling context. Choosing to abstain when you're ahead sends a strong signal to the world - just ask Alejandro Toledo. But choosing to abstain when you're getting clocked in the polls looks far too much like the weasel way out of a bind. This may be unfair - anyone following Venezuelan politics closely over the last few years knows exactly how opaque and partisan CNE has been - but then, politics is about effectiveness, not fairness. The opposition would understand this if it wasn't so obdurate about swallowing its own hype.

Just to be clear, I don't mean to criticize the Opposition's decision to abstain - a decision I share. But I do mean to bring a level of sanity to the overblown expectations some had harbored that abstaining would somehow radically overhaul international perceptions of the Chavez government. Sumate's line, that December 4th marks a critical inflection point in Venezuelan history, seems aggressively optimistic to me. The only real difference, as far as I can tell, is that chavismo will no longer need to amend the National Assembly rules of order every two weeks to do exactly what it wants.

If anything, overall international perceptions hardened yesterday. Setting aside the right and left-wing fringes - and lets face it: Carlos Alberto Montaner and Thor Halvorssen aren't really any more influential than Ignacio Ramonet and Larry Birns - the way the world perceives the political dynamic in Venezuela is that we have a charismatic (if erratic and authoritarian) leftist in power facing a comically immature, by-and-large reactionary Opposition with a tin-ear for politics and a purely defensive stance. Nothing the world saw yesterday goes against the grain of this conventional wisdom.

That's the bed the Opposition leadership made for us, and now we get to lie in it.

Fact is, there are no shortcuts. There is no way to change foreign perceptions until we start winning the political argument in Venezuela. I think this can be done. There are plenty of chavista weaknesses a smart, disciplined, optimistic, forward-looking, savvy opposition could exploit. Chavez may be popular, but his government isn't. Even in the middle of an oil boom, polls show high levels of dissatisfaction with its performance. Chavistas resent its corruption as much as we do, or more. The internal contradictions in the Chavez organization have been simmering for years, and are bound to boil over sooner or later. Popular enthusiasm for the project can't be sustained beyond sporadic spending sprees. People want an alternative.

Those of us who reject Chavez have a year to build that alternative. Now that the Oppo old guard has purged itself from parliament, we have a unique chance to do so freed from the dead-weight of Fourth Republic associations. Vamos a dale...

This is really not so surprising, considering the polling context. Choosing to abstain when you're ahead sends a strong signal to the world - just ask Alejandro Toledo. But choosing to abstain when you're getting clocked in the polls looks far too much like the weasel way out of a bind. This may be unfair - anyone following Venezuelan politics closely over the last few years knows exactly how opaque and partisan CNE has been - but then, politics is about effectiveness, not fairness. The opposition would understand this if it wasn't so obdurate about swallowing its own hype.

Just to be clear, I don't mean to criticize the Opposition's decision to abstain - a decision I share. But I do mean to bring a level of sanity to the overblown expectations some had harbored that abstaining would somehow radically overhaul international perceptions of the Chavez government. Sumate's line, that December 4th marks a critical inflection point in Venezuelan history, seems aggressively optimistic to me. The only real difference, as far as I can tell, is that chavismo will no longer need to amend the National Assembly rules of order every two weeks to do exactly what it wants.

If anything, overall international perceptions hardened yesterday. Setting aside the right and left-wing fringes - and lets face it: Carlos Alberto Montaner and Thor Halvorssen aren't really any more influential than Ignacio Ramonet and Larry Birns - the way the world perceives the political dynamic in Venezuela is that we have a charismatic (if erratic and authoritarian) leftist in power facing a comically immature, by-and-large reactionary Opposition with a tin-ear for politics and a purely defensive stance. Nothing the world saw yesterday goes against the grain of this conventional wisdom.

That's the bed the Opposition leadership made for us, and now we get to lie in it.

Fact is, there are no shortcuts. There is no way to change foreign perceptions until we start winning the political argument in Venezuela. I think this can be done. There are plenty of chavista weaknesses a smart, disciplined, optimistic, forward-looking, savvy opposition could exploit. Chavez may be popular, but his government isn't. Even in the middle of an oil boom, polls show high levels of dissatisfaction with its performance. Chavistas resent its corruption as much as we do, or more. The internal contradictions in the Chavez organization have been simmering for years, and are bound to boil over sooner or later. Popular enthusiasm for the project can't be sustained beyond sporadic spending sprees. People want an alternative.

Those of us who reject Chavez have a year to build that alternative. Now that the Oppo old guard has purged itself from parliament, we have a unique chance to do so freed from the dead-weight of Fourth Republic associations. Vamos a dale...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)