Juan Cristobal says: - One of the biggest challenges in writing this blog is bridging the disconnect between our perception of Venezuelan politics and the day-to-day reality on the ground. While I firmly believe that distance isn't an impediment to staying well informed (in fact, it's a huge plus), I realize it tends to deaden our feel for the ironies and contradictions of life in revolutionary times.

Juan Cristobal says: - One of the biggest challenges in writing this blog is bridging the disconnect between our perception of Venezuelan politics and the day-to-day reality on the ground. While I firmly believe that distance isn't an impediment to staying well informed (in fact, it's a huge plus), I realize it tends to deaden our feel for the ironies and contradictions of life in revolutionary times.Sure, distance allows us to provide a different perspective, but what if we end up becoming a bunch of curmudgeons? What if the Revolution is, deep down, just another cague de risa? What if our focus on the trees that are the day-to-day outrages prevents us from seeing the farcical forest that is Chavez's Venezuela?

A few weeks ago I was in Caracas for the wedding of a college buddy of mine. The wedding was held at La Esmeralda, the flagship of the prestigious Agencia Mar, Venezuela's top provider of quality, conspicuous, over-the-top, unabashedly in-your-face-expensive entertainment. La Esmeralda had long been the premium spot for Caracas social life and a fixture in big events for the past twenty years, but I somehow assumed it was past its prime.

I remember my first wedding at La Esmeralda. It was back in 1989, in the weeks following El Caracazo. You could sense the country was changing, but here I was, a college sophomore, fresh out of Maracaibo, with my date, in a lavish ballroom, being treated like a king. The canapés were succulent, and they just kept coming. The Scotch was 12-year-old Black Label, of course, and the champagne was French, obviously. The live orchestra was on fire, and I remember we danced til 5 in the morning. It was, for lack of a better word, memorable.

But there was also an eerie feel to the proceedings, as if we were waltzing in the Titanic oblivious to the icebergs all around us. I wasn't aware of it then, but I can't help recalling those days without a certain sense of dread. It's as if 37-year-old me wanted to go back in time and warn 18-year-old me about how fake it all was, how it was all going to go up in smoke.

I didn't know what to expect this time around. I hadn't been to La Esmeralda in years. In the interim, fortunes have been made and lost (and remade and relost) and the Revolution plows through, taking no prisoners. I was expecting it to be the decadent reminder of better times, a lonely ballroom waiting to be nationalized.

Silly me, I found myself in the middle of a swank party unlike any I'd ever seen: a bonche worthy of the dizzying petroboom we're having.

There was champagne like the last time, only it kept flowing until 5 in the morning. The band was on fire as well, only it, too, played until the wee hours. There was a sushi bar, a Chinese chef, and a dessert bar to kill for, with thousands of individual chocolate-and-cream concoctions I don't even have names for. I left at close to 6 in the morning, and there was enough food left over to feed a small orphanage for days.

As I was soaking it all in, having a great time, I suddenly remembered: wait, wasn't this supposed to be a Revolution? Don't these people read the newspapers? In which chapter of Das Kapital is the bit about the sushi bars? I haven't had this much fun in years!

The dissonance, she is strong. Somehow, nine years into the Cuban revolution, I don't think Fidel's opponents were throwing bashes where the towels in the bathroom were monogrammed with the initials of the bride and groom. And I just have a strong feeling that, by 1927, anti-bolsheviks in Russia were not getting married in mansions that gave away baskets upon baskets of cosmetics, sewing kits, hair accessories and glossy magazines in the ladies' room.

I told my friends how impressed I was with the lavish attention and how cool the party was, but also how weird it felt to be there when this was supposed to be a socialist revolution. They smiled back at me, saying that I hadn't seen nothin': one time they went to a boliburgués wedding in La Esmeralda where the bride's mother had demanded furniture be flown in from France to enhance the art-deco motif they were gunning for.

The more things change, the better they get. Chávez may throw out the American Ambassador, milk may be hard to come by, crime may reach unheard-of heights and war with Colombia may be imminent..."pero como se goza...!"

As long as the gush of petrodollars keeps swamping the country, a good time can be had by...a few.

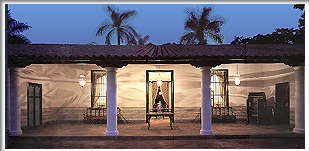

PS.- As I was writing this, I got this gotta-see-it-to-believe-it video showcasing the wedding of chavista ideologue William Izarra (Information Minister Andrés Izarra's dad) and his very young, very pregnant wife. Chavistas, like the rest of us, enjoy a good bonche, [UPDATE: Ooops, turns out the wedding was held not in Quinta Anauco, as I'd first thought, but in the Casona Anauco Arriba, a related property that doesn't house a museum.]

(I wonder if they bothered to move the museum collection out before the big bash, or if they just partied with the Marqués del Toro's stuff.)

I don't know if, like Freddy Bernal says, it's the first wedding to be held there in 400 years, but I sure hope it's the last.