July 15, 2006

July 14, 2006

How to win with crime...

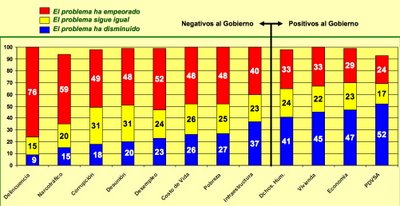

Crime is the issue Venezuelans are most worried about. It's also the issue where they rate Chavez's performance worst. Here's Keller's June 2006 Performance-by-Issue slide:

[Click to expand. Red=Problem is getting worse. Yellow = Problem is the same as ever. Blue = Problem is getting better.]

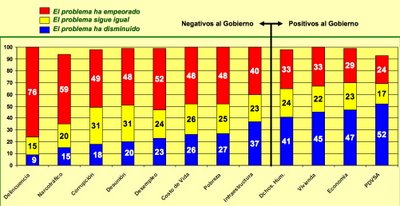

[Click to expand. Red=Problem is getting worse. Yellow = Problem is the same as ever. Blue = Problem is getting better.]

Somehow, though, the opposition can't get any traction on it. The problem is that, today, crime is just not a politicized issue. That's because Chavez just won't join the fray. The most amazing thing about Chávez's line on the crime epidemic is that he doesn't have one. And when the other side fails to acknowledge the issue, it's impossible to establish a discussion.

How does the opposition change this dynamic? It's tough. But one possible avenue is to talk about crime as a social and economic issue. This is something Tony Blair managed to do with his now famous "tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime" campaign line. By underlining the links between poverty, exclusion and urban violence, the opposition can use the sharp rise in crime to tell a story about the overall social failure of the regime - who's ever heard a country where rapid poverty abatement and social inclusion go hand in hand with an unprecedented crime wave? The story doesn't hang together.

The opposition badly needs to make the December election about its strongest issue. It needs to grab control of the agenda, something it's catastrophically failed to do since 2003. The protests surrounding the deaths of the Fadoul brothers showed that there's an substrate of anger around insecurity, that crime is politicizable. Time to move on this.

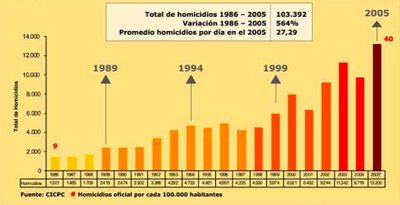

Venezuela's Murder Rate: Click here to expand

Venezuela's Murder Rate: Click here to expand

Addendum: Some of the crimes being reported these days are just jaw-dropping in their audacity. On Wednesday, at 5 a.m. in Guatire, a group of thugs held up fourteen buses in one go in a commando-style operation.

[Click to expand. Red=Problem is getting worse. Yellow = Problem is the same as ever. Blue = Problem is getting better.]

[Click to expand. Red=Problem is getting worse. Yellow = Problem is the same as ever. Blue = Problem is getting better.]Somehow, though, the opposition can't get any traction on it. The problem is that, today, crime is just not a politicized issue. That's because Chavez just won't join the fray. The most amazing thing about Chávez's line on the crime epidemic is that he doesn't have one. And when the other side fails to acknowledge the issue, it's impossible to establish a discussion.

How does the opposition change this dynamic? It's tough. But one possible avenue is to talk about crime as a social and economic issue. This is something Tony Blair managed to do with his now famous "tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime" campaign line. By underlining the links between poverty, exclusion and urban violence, the opposition can use the sharp rise in crime to tell a story about the overall social failure of the regime - who's ever heard a country where rapid poverty abatement and social inclusion go hand in hand with an unprecedented crime wave? The story doesn't hang together.

The opposition badly needs to make the December election about its strongest issue. It needs to grab control of the agenda, something it's catastrophically failed to do since 2003. The protests surrounding the deaths of the Fadoul brothers showed that there's an substrate of anger around insecurity, that crime is politicizable. Time to move on this.

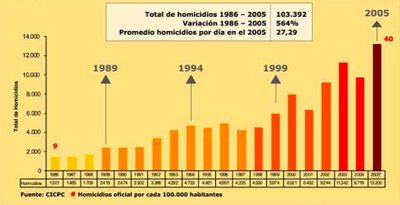

Venezuela's Murder Rate: Click here to expand

Venezuela's Murder Rate: Click here to expandAddendum: Some of the crimes being reported these days are just jaw-dropping in their audacity. On Wednesday, at 5 a.m. in Guatire, a group of thugs held up fourteen buses in one go in a commando-style operation.

July 13, 2006

Making Crime Pay

From a polling perspective, it's a no-brainer. The issue most people identify as the country's biggest problem is also the one where they rate Chavez's performance the worst.

According to Hinterlaces' May/June 2006 poll, 87% of voters identify crime is the biggest problem in the country. 70% say crime has gotten worse under Chavez, and 24% say it's the same as it's always been.

Keller's June poll also identifies crime as the number one issue - 76% of his respondents think it's gotten worse and 15% say it's the same.

How should a savvy oppo candidate react?

By talking about very little else.

According to Hinterlaces' May/June 2006 poll, 87% of voters identify crime is the biggest problem in the country. 70% say crime has gotten worse under Chavez, and 24% say it's the same as it's always been.

Keller's June poll also identifies crime as the number one issue - 76% of his respondents think it's gotten worse and 15% say it's the same.

How should a savvy oppo candidate react?

By talking about very little else.

Chavista Assembly Members Demand Dissidents be Jailed

Pro-Chavez National Assembly Members José Albornoz (PPT) and Ismael García (Podemos) are asking the Prosecutor General to jail Sumate's leaders.

Their crimes? Usurping the CNE's prerogative by seeking to organize a primary election outside the state's control and incitement for publicly airing their views on CNE.

Still more proof that chavismo, as an ideology, has no room for the idea that some matters are not the state's business - that there are spaces where citizens can and should come to make decisions without the state's interference. We already saw this in 1999 when chavismo insisted that labor union elections had to be organized by CNE, and in 2003 when they said that signature-gatherings had to be run by CNE.

The notion that citizens can use whichever method they deem best to select their candidate for election is beyond them. The concept of civil society - of a sphere of social life that is both public and outside the state's control - is deeply alien to their understanding of the good society. By this reasoning, voting for Miss Venezuela will end up having to be organized by CNE.

Extremism? What extremism?

Their crimes? Usurping the CNE's prerogative by seeking to organize a primary election outside the state's control and incitement for publicly airing their views on CNE.

Still more proof that chavismo, as an ideology, has no room for the idea that some matters are not the state's business - that there are spaces where citizens can and should come to make decisions without the state's interference. We already saw this in 1999 when chavismo insisted that labor union elections had to be organized by CNE, and in 2003 when they said that signature-gatherings had to be run by CNE.

The notion that citizens can use whichever method they deem best to select their candidate for election is beyond them. The concept of civil society - of a sphere of social life that is both public and outside the state's control - is deeply alien to their understanding of the good society. By this reasoning, voting for Miss Venezuela will end up having to be organized by CNE.

Extremism? What extremism?

July 12, 2006

On the nature of verbal agression

Katy says: The debate that raged in the comments section (see Quico's prior post and the discussion that followed) got me thinking about the power of words. The right words said in the right context, be they Chávez's, Quico's, Alek Boyd's or Materazzi's, can be a powerful tool. They can inspire fear, apprehension, ridicule. They can send people into a tizzy, or send them straight to the nearest airport or locker room. They can provoke a reasonable, inspired response, or they can provoke an act of violence tinged with just the right amount of honor.

But I'm not a good enough writer to talk about these things. Here's what tennis writer/blogger Peter Bodo had to say about Zidane's infamous head-butt. I think there's some truth in there for all of us.

"What Zidane did was undoubtedly stupid. It was silly. It may have cost France a most magically earned World Cup championship, and it cost Zidane himself a fair amount of the glow surrounding his name.

But I also think this: Zidane was driven to butt Italian Marco Materazzi out of a sense of personal honor (you certainly can’t say Zidane acted in the heat of the moment), because Materazzi crossed a line in the sand. And that notion of “honor” is almost entirely gone from our collective life these days.

Theoretically, we should be living in a time of civility and harmony, because we’ve managed to create powerful prohibitions against things like the good old-fashioned punch-in-the-nose. Actually, it appears that we’ve thrown open the floodgates on incivility, reckless accusation (and lying), the vilest kinds of name-calling, bigotry - the whole nine – because nobody is held accountable anymore. Therefore, a guy like Materazzi (I'm basing all this on admittedly unsatisfying press reports) feels he can say anything he wants - Zidane wouldn't dare hold him accountable. Not with millions watching! Not with all that money at stake! Not with the precious World Cup trophy on the line!

But every once in a while, somebody – today, it’s Zidane - violates the taboo. He or she in effect, says, I don’t care what is on the line, how much money or personal advantage or reward. I am not going to have the last laugh, or laugh all the way to the bank. My code of honor simply won’t allow me to let this go unanswered. It takes an individual of great (if not necessarily admirable) character to take that road, and wasn’t Mr. Materazzi surprised to learn, in the most direct manner, that he was being held accountable for his words?

I don't expect many of you to agree with me on this. But I can't deny the way I feel about this. Of course, a part of me feels badly for the French squad, which inadvertently suffered because of what Zidane felt he had to do. But a part of me condones what Zidane did and forgives him because, in addition to striking a blow for accountability, his action also demonstrated something that many people forget and that as a writer I feel strongly about: words are powerful weapons, they can cause more hurt and sorrow than fists or belts or willow switches.

...

The head butt was about the power of words, the notion of accountability, and about honor. It was not an admirable move, nor a clever or practical one; it was something that transcended those mundane considerations."

July 11, 2006

Chavista Extremism: Scarier and scarier...

Extremism is becoming the defining characteristic of the chavista movement. At no point does the ruling ideology draw the line - just the opposite: every part of the new elite seems to operate under the maxim that if a little extremism is good, a lot is better. The result is a kind of tournament within the regime, a dynamic of one-upmanship where each tries to out-extremist the other.

It's a scary thing: the phrase "that's going too far" doesn't seem to be a part of the regime's political lexicon. More and more, the regime has lost its feel for the ridiculous (el sentido del ridículo) - leaving it shorn of any way to judge how much is too much.

Examples? They're a dime a dozen. Here are a few:

We need to be clear about this: Venezuela is not a totalitarian regime. But we also need to be clear about this: it is moving more and more decisively in that direction. Clearly, spaces for dissent still exist; just as clearly, the regime is working to close them down.

What's terrifying is that there is no logical limit to chavismo's power ambition. Nothing in the structure of the belief system limits its tendency to expand control into new areas of political and - more and more - social life.

There is no room in chavista thinking for the notion that some of spheres of human activity are and ought to remain outside of the political sphere. And there is certainly no space in chavista thinking for the notion that any part of the political sphere ought to remain outside the state's control. It's a way of conceiving politics that never says "enough," that has no notion of "that's not the state's business," that never sees a reason to stop expanding its reach, and that does not recognize any distinctions between the concepts of "nation", "state", "government", "party" and "Chavez." As far as the ruling ideology is concerned, to be for one of those is to be for all of them; to oppose one is to oppose them all.

What's scary is not so much where we are now, but where the internal logic of chavista thinking points us. These days people are happy buying their hummers and plasma TVs and such. But the logic of blanket politization is afoot, and with it the mechanisms first for authoritarian and later for totalitarian control.

We're definitely not there. Chavismo's myriad internal contradictions might yet cause its collapse before we get there. But it's not really possible to deny that we're heading there. Not any more.

It's a scary thing: the phrase "that's going too far" doesn't seem to be a part of the regime's political lexicon. More and more, the regime has lost its feel for the ridiculous (el sentido del ridículo) - leaving it shorn of any way to judge how much is too much.

Examples? They're a dime a dozen. Here are a few:

- The Armed Forces' Polytechnic University awards an honorary doctorate to an aging Mikhail Kalashnikov for his lifetime contribution to the noble cause of figuring out how to kill people efficiently.

- A Cuban communist guerrillero who literally led an armed invasion against Venezuela's democratically elected government is honored in a public ceremony by regime hierarchs (handily exceeding the DDefinition of supporting terrorism") and the news is proudly splashed on pro-government websites.

- Thousands of Venezuelan kids go off to Cuba for paramilitary and ideological training, come home, and get 15,000 assault rifles bought with public money. Among their slogans - Commandante Chavez: Ordene!

- Practically alone in the world, Venezuela sets out a principled defense of North Korea's right to develop ICBMs, essentially celebrating its missile tests as an anti-imperialist move in the eve of Chavez's visit to Pyongyang.

- The National Assembly moves to further restrict the scope for NGO action, with the avowed aim of bringing them under control.

- A literally gun-toting president threatens to shut down opposition TV and radio stations, saying it is unacceptable for the media to criticize the government.

- Essentially all high-profile opposition elected officials still in office are prosecuted on trumped up charges or threatened with prosecutions if they do not behave as the regime demands.

- Even the Venezuelan Olympic Committee is taken over by a chavista aparatchik.

We need to be clear about this: Venezuela is not a totalitarian regime. But we also need to be clear about this: it is moving more and more decisively in that direction. Clearly, spaces for dissent still exist; just as clearly, the regime is working to close them down.

What's terrifying is that there is no logical limit to chavismo's power ambition. Nothing in the structure of the belief system limits its tendency to expand control into new areas of political and - more and more - social life.

There is no room in chavista thinking for the notion that some of spheres of human activity are and ought to remain outside of the political sphere. And there is certainly no space in chavista thinking for the notion that any part of the political sphere ought to remain outside the state's control. It's a way of conceiving politics that never says "enough," that has no notion of "that's not the state's business," that never sees a reason to stop expanding its reach, and that does not recognize any distinctions between the concepts of "nation", "state", "government", "party" and "Chavez." As far as the ruling ideology is concerned, to be for one of those is to be for all of them; to oppose one is to oppose them all.

What's scary is not so much where we are now, but where the internal logic of chavista thinking points us. These days people are happy buying their hummers and plasma TVs and such. But the logic of blanket politization is afoot, and with it the mechanisms first for authoritarian and later for totalitarian control.

We're definitely not there. Chavismo's myriad internal contradictions might yet cause its collapse before we get there. But it's not really possible to deny that we're heading there. Not any more.

July 10, 2006

The 2006 PSF D'Or goes to...

Envelope please...[rustle-rustle, cough]...Ladies and Gentlemen, the 2006 Pendejo sin Fronteras d'Or goes to...Chris Kraul, of the Los Angeles Times!

It's no contest, really: his piece in Sunday's LAT about the ways chavistas have been using Charlie Chaplin's 1936 classic, Modern Times, for propaganda purposes will go down as a timeless classic of slack-jawed PSFery. The story misreports, misunderstands, misconstrues and misattributes Venezuelan workers' problems with such gusto, the competition didn't have a chance.

A taste:

In a way, the first thing that jumps out at you is not so much Kraul's staggering ignorance as his utter lack of inquisitiveness. The piece details the way chavistas have used Modern Times to make a point about labor exploitation in Venezuela. A minimally curious writer might then ask, "hmmmm, are labor conditions in Venezuela today really comparable to labor conditions in the US during the depression? Do Venezuelan workers really have no meaningful rights? does it really make sense to describe Chaplin's film as 'all too relevant' in Venezuela?"

Well, lets see, what were workers fighting for in the 1930s in the US? First and foremost, they were worried about the right to form unions and bargain collectively...rights that have been guaranteed and widely exercised in Venezuela since 1958.

Bad start. OK, the minimum wage, then? Nope, there has been a minimum wage in Venezuela, for decades. Not only that, figured as a percentage of the average wage, Venezuela's minimum wage is the highest in the America's - fully 90% of the average, meaning that, for all intents and purposes, Venezuelan wages as a whole are decreed by the Central Government.

Not that either, then. Perhaps the eight hour work day is a good parallel? Nope, Venezuelan workers got that reivindicación decades ago. Vacation pay? Got it. Severance pay? Got it. Mandatory employer contributions to pensions? Got those too. Statutory overtime pay premiums? Check.

Hmmm...how about some more lavish perks - the kinds of things European workers protest over these days? Statutory employer-provided childcare and dining facilities, say, or an open-ended ban on layoffs, or subsidized housing, subsidized worker training, subsidized transport, or statutory profit-sharing, or paid maternity leave? Hell, these are demands that would have made US workers blush back in the 30s - but, you guessed it, Venezuelan workers have all of those as well!

In fact, Venezuela has some of the most restrictive, rigid, employment-zapping labor legislation anywhere in the world.

So restrictive is the legal framework that in the paper I wrote about yesterday, Hausmann and Rodriguez set out microeconomic evidence showing how labor market rigidities have hampered Venezuela's attempts to crack non-energy export markets, deepening our dependence on oil exports and contributing to the country's economic collapse since 1977.

In effect, with existing legislation, the legal economy can't begin to generate enough jobs for the size of the workforce we have, leaving about half of Venezuelan workers to scrape together a living somehow in the informal sector. Once there, they have no protections whatsoever. UCAB researchers have found that 90% of informal sector workers earn less than the legal minimum wage. It's hardly surprising that, for informal workers, finding a job in the "savage capitalist" economy Modern Times sends up is a universal aspiration, a wistful dream that's simply out of their reach.

Given the very high costs associated with Venezuela's hypertrophied labor legislation, it's easy to see why the informal sector has swelled. Venezuela has a plainly outsized "fiscal wedge" (cuña fiscal) - the gap between what it costs an employer to create a legal job, and the pay a worker effectively takes home. By some researchers' estimates, every Bs.100 in take-home pay for legal workers costs employers Bs.171 to generate - with the extra Bs.71 going to cover various taxes, mandatory contributions, and statutory workplace perks. These figures dwarf the notorious fiscal wedges in countries like Germany (51%), Belgium (56%) and France (47%).

For all his efforts to "even-handedly" present business viewpoints in his piece, Kraul catastrophically fails to grasp the basic ridiculousness of the way Modern Times is being used to push an extremist ideological agenda. What Kraul tragically fails to process is that Venezuela's legal labor force is a relatively privileged elite within the working class, the better-off half in a vicious insider-outsider dynamic that condemns millions of people to the atrocious poverty and total insecurity of the gray economy...and that the more legal goodies that relatively privileged elite gets, the more expensive it gets to create legal jobs, and the harder outsiders find it to crack into the legal job market.

Maybe, on his way back to the Meliá from that poultry plant, Kraul should've stopped to chat with some of the buhoneras in the Boulevard de Sabaná Grande and asked them what they think about the terrible exploitation of the quince-y-último set. The look of baffled fury he would've gotten from them perfectly mirrors my outrage at his deeply ignorant little piece.

His, dear reader, is one richly deserved PSF D'Or...

It's no contest, really: his piece in Sunday's LAT about the ways chavistas have been using Charlie Chaplin's 1936 classic, Modern Times, for propaganda purposes will go down as a timeless classic of slack-jawed PSFery. The story misreports, misunderstands, misconstrues and misattributes Venezuelan workers' problems with such gusto, the competition didn't have a chance.

A taste:

Since January, in a bid to expose the evils of "savage capitalism," the Labor Ministry has shown the Chaplin film to thousands of workers in places such as this rundown industrial suburb of Caracas.Chaplin wanted his Depression-era movie to make a point, that "once inside the factory, workers had no meaningful rights," said Los Angeles-based film historian and Chaplin authority Richard Schickel. "It was very relevant in the moment it was released, a time of social unrest and the emerging U.S. labor movement."

Seventy years later, Chaplin's fable is all too relevant in Venezuela, said several factory workers who saw the film recently.

In a way, the first thing that jumps out at you is not so much Kraul's staggering ignorance as his utter lack of inquisitiveness. The piece details the way chavistas have used Modern Times to make a point about labor exploitation in Venezuela. A minimally curious writer might then ask, "hmmmm, are labor conditions in Venezuela today really comparable to labor conditions in the US during the depression? Do Venezuelan workers really have no meaningful rights? does it really make sense to describe Chaplin's film as 'all too relevant' in Venezuela?"

Well, lets see, what were workers fighting for in the 1930s in the US? First and foremost, they were worried about the right to form unions and bargain collectively...rights that have been guaranteed and widely exercised in Venezuela since 1958.

Bad start. OK, the minimum wage, then? Nope, there has been a minimum wage in Venezuela, for decades. Not only that, figured as a percentage of the average wage, Venezuela's minimum wage is the highest in the America's - fully 90% of the average, meaning that, for all intents and purposes, Venezuelan wages as a whole are decreed by the Central Government.

Not that either, then. Perhaps the eight hour work day is a good parallel? Nope, Venezuelan workers got that reivindicación decades ago. Vacation pay? Got it. Severance pay? Got it. Mandatory employer contributions to pensions? Got those too. Statutory overtime pay premiums? Check.

Hmmm...how about some more lavish perks - the kinds of things European workers protest over these days? Statutory employer-provided childcare and dining facilities, say, or an open-ended ban on layoffs, or subsidized housing, subsidized worker training, subsidized transport, or statutory profit-sharing, or paid maternity leave? Hell, these are demands that would have made US workers blush back in the 30s - but, you guessed it, Venezuelan workers have all of those as well!

In fact, Venezuela has some of the most restrictive, rigid, employment-zapping labor legislation anywhere in the world.

So restrictive is the legal framework that in the paper I wrote about yesterday, Hausmann and Rodriguez set out microeconomic evidence showing how labor market rigidities have hampered Venezuela's attempts to crack non-energy export markets, deepening our dependence on oil exports and contributing to the country's economic collapse since 1977.

In effect, with existing legislation, the legal economy can't begin to generate enough jobs for the size of the workforce we have, leaving about half of Venezuelan workers to scrape together a living somehow in the informal sector. Once there, they have no protections whatsoever. UCAB researchers have found that 90% of informal sector workers earn less than the legal minimum wage. It's hardly surprising that, for informal workers, finding a job in the "savage capitalist" economy Modern Times sends up is a universal aspiration, a wistful dream that's simply out of their reach.

Given the very high costs associated with Venezuela's hypertrophied labor legislation, it's easy to see why the informal sector has swelled. Venezuela has a plainly outsized "fiscal wedge" (cuña fiscal) - the gap between what it costs an employer to create a legal job, and the pay a worker effectively takes home. By some researchers' estimates, every Bs.100 in take-home pay for legal workers costs employers Bs.171 to generate - with the extra Bs.71 going to cover various taxes, mandatory contributions, and statutory workplace perks. These figures dwarf the notorious fiscal wedges in countries like Germany (51%), Belgium (56%) and France (47%).

For all his efforts to "even-handedly" present business viewpoints in his piece, Kraul catastrophically fails to grasp the basic ridiculousness of the way Modern Times is being used to push an extremist ideological agenda. What Kraul tragically fails to process is that Venezuela's legal labor force is a relatively privileged elite within the working class, the better-off half in a vicious insider-outsider dynamic that condemns millions of people to the atrocious poverty and total insecurity of the gray economy...and that the more legal goodies that relatively privileged elite gets, the more expensive it gets to create legal jobs, and the harder outsiders find it to crack into the legal job market.

Maybe, on his way back to the Meliá from that poultry plant, Kraul should've stopped to chat with some of the buhoneras in the Boulevard de Sabaná Grande and asked them what they think about the terrible exploitation of the quince-y-último set. The look of baffled fury he would've gotten from them perfectly mirrors my outrage at his deeply ignorant little piece.

His, dear reader, is one richly deserved PSF D'Or...

July 9, 2006

Skypecast: Francisco Rodríguez on Venezuela's Economic Collapse

Click here to listen to the interview.

This interview features Francisco Rodríguez. Francisco is Assistant Professor of Economics and Latin American Studies at Wesleyan University, and a fast rising academic star. He's currently co-editing a book on Venezuela's economic collapse with Harvard's Ricardo Hausmann. Over the next few weeks I will be publishing Skypecasts with several of the book's contributors.

This interview features Francisco Rodríguez. Francisco is Assistant Professor of Economics and Latin American Studies at Wesleyan University, and a fast rising academic star. He's currently co-editing a book on Venezuela's economic collapse with Harvard's Ricardo Hausmann. Over the next few weeks I will be publishing Skypecasts with several of the book's contributors.

Working drafts of all the book's chapters can be downloaded here.

In this wideranging, 40-minute Skypecast, Francisco describes the overall research project, and then walks us through the draft chapter he co-authored with Ricardo Hausmann. In explaining Venezuela's economic collapse, Hausmann and Rodríguez stress the fact that Venezuela didn't have an alternative export industry to cushion the blow when oil prices fell. They go on to assess five different hypotheses to explain why, unlike Mexico, Indonesia and Malaysia, Venezuela didn't develop alternative export industries.

The Skypecast sets out their research in language that (I hope) will be understandable to non-specialists. Towards the end, Francisco explains some of the policy implications of his analysis.

Click here to listen to the interview.

This interview features Francisco Rodríguez. Francisco is Assistant Professor of Economics and Latin American Studies at Wesleyan University, and a fast rising academic star. He's currently co-editing a book on Venezuela's economic collapse with Harvard's Ricardo Hausmann. Over the next few weeks I will be publishing Skypecasts with several of the book's contributors.

This interview features Francisco Rodríguez. Francisco is Assistant Professor of Economics and Latin American Studies at Wesleyan University, and a fast rising academic star. He's currently co-editing a book on Venezuela's economic collapse with Harvard's Ricardo Hausmann. Over the next few weeks I will be publishing Skypecasts with several of the book's contributors.Working drafts of all the book's chapters can be downloaded here.

In this wideranging, 40-minute Skypecast, Francisco describes the overall research project, and then walks us through the draft chapter he co-authored with Ricardo Hausmann. In explaining Venezuela's economic collapse, Hausmann and Rodríguez stress the fact that Venezuela didn't have an alternative export industry to cushion the blow when oil prices fell. They go on to assess five different hypotheses to explain why, unlike Mexico, Indonesia and Malaysia, Venezuela didn't develop alternative export industries.

The Skypecast sets out their research in language that (I hope) will be understandable to non-specialists. Towards the end, Francisco explains some of the policy implications of his analysis.

Click here to listen to the interview.

Talk vCrisis here...

Personally, I've been careful not to say much about the Boyd-Livingston saga. My deep disagreements with Alek are just as public as our friendship is. However, there seems to be a limitless appetite to discuss this, so I'll open this thread for that purpose.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)