Death at Dawn

by Aliana Gonzalez, photos by Ilich Otero

reprinted from the Jan. 21st edition of TalCual, translated by me

Rusleidy Lopez is still scared.

The policeman was very clear: "if ever we find out you've said anything, we're coming back for you". On Monday, at 3:00 p.m., they went by the house dressed as civilians, armed, with their bullet-proof vests on and yelled "the women of this barrio are going to cry tears of blood." That night, she decided to sleep at her mom's place again.

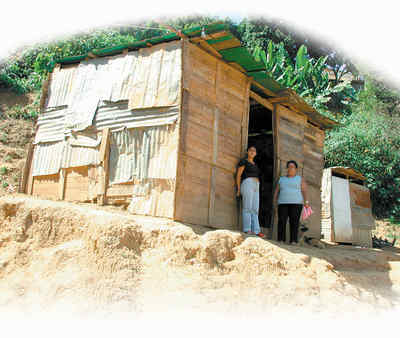

Rusleidy's home

The splattered blood that Orlando Jovany Sosa, her husband, left as he died is still visible on the wood and zinc walls, papered over with newsprint and magazine covers. On january 8th, at 4 in the morning, Policaracas (Caracas Municipal Police officers) and CICPC officers arrived at her house dressed in black and wearing ski masks. Some let their faces be seen.

"We were sleeping," she says "and I heard steps. I got up from bed, peered through a hole, and I saw the alley was full of policemen. I woke up Jovany. They kicked down the door, came in, and threw me out of the house. They took me into the woods and told me to stay there, because otherwise they would kill me as well. A quarter of an hour later they fired into the dumpster. Then they asked me 'what was the name of your husband?' 'Orlando,' I said, but they say 'you lie, they used to call him the Zombie.'"

Rusleidy had her twentythird birthday yesterday.

She had lived with Jovany for five years, when he was 15 and she 17. Her house was a small room with a dirt floor and a bed as the only furniture.

The kitchen - a two-burner gas stove - is set on top of an overturned bucket, almost at floor level. In big bags she keeps what little she owns.

The house has no drinking water, she has to keep some in a pitcher. The bathroom is a letrine.

There is no fridge, no closet, no cupboards.

Rusleidy at home

This "Mata de Mango" area, in the El Setenta shantytown of El Valle, is on the edge of the city, near the woods. Even though misery is the rule, they enjoy a unique view of the city: you can see the Helicoide, the cementery, the highway and even Las Acacias.

Forced to sign

Rusleidy was taken that day to CICPC - the investigative police [equivalent to the FBI.] Dawn was breaking.

"They grabbed me by the sweater," she says, "then by the neck and they put a gun to my ribs. I told them they were choking me and another officer said to let me go. When my mom and dad arrived, they threw me in a patrol car. I still didn't know what had happened to Jovany."

"I was in an office at CICPC headquarters until 9:30 that morning."

"An officer came and told me: 'you know that your husband didn't have a shootout with us, but we killed him because he's being accused of murder.'"

"They told me they would write a letter, and that if I didn't sign it, then I would pay for what they'd found in the house. The letter said that Jovany was running away from the cops, he took shelter at the house, had a shootout with them, but I managed to escape."

In the house, the cops found a gun and a little money.

"I don't know whose gun it is. I know Jovany was keeping it. The money was mine, from my work as a street hawker." After signing, the cops told her that "it's very dangerous to mess with the police; don't even think about making a formal complaint."

Look me in the face

Migdales Gonzalez, on the other hand, is not scared. She's the mother of Kelvin Gonzalez, who was killed by the same officers one hour later, at the other end of the barrio.

The version published in the press is that both had shootouts with the police. On top of the long distance between the two houses, there's the fact that neither had bullet holes on the walls, making the hypothesis fragile.

"I'm over my fear," Migdalis says, "I told the cop the same day they killed Kelvin: look me in the face, you killed my son and I'm not going to stay quiet about it, so you can go look for me at home to kill me."

Gonzalez is indignant with the director of the Policaracas for his statements.

"He said that everybody in this barrio is into drugs, that that's why they didn't say Kelvin and Jovany were neighborhood bullies. I've been working every day for years, and I am a respectable woman. People here get up early in the morning and go work and sweat for their money. Doesn't he respect people? I'm indignant that that is the explanation he gives, faced with the truth of the barrio. If they were really involved in shooting a cop, why didn't they arrest them and try them, so they could pay for their crime?"

In El Setenta the police has taken five lives, in similar circumstances, in less than four months.

Daniel Centeno, on October 9th, Cesar Augusto Kacen, four days later.

Daniel Centeno's dad

Kacen was 43 years old and was a nightwatchman in the public transport parking lot, on the barrio's sports field. At about 11:30 at night on 13th of October, Policaracas went up there. He was on the court, waiting for the minibuses.

A neighbor heard him beg and screem, calling for his mom, before the gunshot. "We buried Cesar ourselves because he had no family. His family moved away from the barrio years ago, and he stayed behind. He made a living carrying gas tanks, sand bags, and lately as a watchman. He had his problems, but he's grown up and he never messed with anyone," said Migdalis Gonzalez.

The other victim is Edison Jose Mendez. It was on December 12th, in identical circumstances as Jovany Sosa and Kelvin Gonzalez. Policaracas went in with ski masks, at 6 a.m., kicked out his family members, shot him, and then spread the word that he'd died in a shootout.