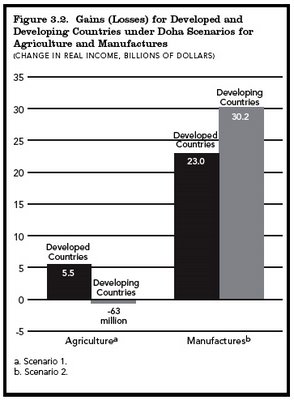

That Carnegie Endowment paper is pretty explicit on this point: it's the EU and Japan that stand to gain most from a Doha Agreement. Thing is, those are the negotiating partners pushing hardest to stop a deal. Even more strange is the fact that, against conventional wisdom, developed countries would be big winners from an agriculture agreement, while developing countries would lose, in the aggregate, from a farm deal.

Welcome to the upside-down world of WTO negotiations!

The reason this happens is that what's good for the EU on aggregate is not what's good for politically influential constituencies in the EU.

In fact, the main source of gains for the EU from an aggricultural deal comes not from gaining access to foreign markets, but merely from being freed from the deadweight of the wasteful tariffs and subsidies to farmers that now weigh down the EU budget. The EU's $90 billion a year common agricultural policy and high tariffs on imported food hurts, first and foremost, EU citizens, who end up paying more in taxes (to pay for subsidies) and more on food (which sells at inflated prices.) By agreeing to withdraw those tariffs and subsidies, the EU could lessen its tax burden, make food cheaper for consumers, and improve the prospects of agricultural exporters in the rest of the world. Everybody wins, right?

Well, no. Not quite. EU farmers definitely lose in such a scenario, and lose big, since they currently get almost half of their revenue from Brussels handouts. It's those farmers who are mobilized against a deal. They're 2% of the EU's population, but they're organized, mobilized, savvy, and have the best lobbyists money can buy. At this point, they more or less own Brussels' trade policy - and they've worked hard to make sure the European Commission adopts a negotiating stance so rigid that no agreement is really possible in the next two weeks. (The same story, more or less, goes for farmers in Japan, South Korea, Norway and Switzerland.)

The other point is that the main gains to be had from a WTO deal are nothing to do with trade negotiations, as such. The developed countries could achieve most of these gains on their own, without having to negotiate with anyone, by just dropping their counterproductive tariffs and subsidies on their own.

Is this screwed up? Well, from an economic point of view, it certainly is. From a political point of view, though, it's perfectly understandable.

Trade reform spreads gains and losses unevenly. If the EU cuts farm tariffs and subsidies, the benefits are evenly spread out between 400 million consumer. But the costs are concentrated among just 8 million farmers. Numerically, the gains to the 400 million consumer are far larger than the losses to the 8 million farmers. But for any individual European consumer the gains are too small to really make a dent, whereas for any individual European farmer the losses are large enough to put them out of business.

Is it surprising that European farmers organize and lobby hard to prevent reform? Not really. Is it really surprising that European consumers can't be bothered? Not really.

Still, the end result is this bizarre state of affairs where EU negotiator work feverishly to stop a deal that would benefit the EU the most, and developing country ministers maneouver feverishly to clinch an agreement that would, on the whole, hurt them.