At the center of their interpretation is the argument that the absence of an alternative export industry left Venezuela badly exposed to energy market shocks. Unlike countries like Mexico, Indonesia and Malaysia that managed to diversify their export baskets, Venezuela's nearly complete specialization in energy (and energy-related) exports amplified the impact of sporadic oil price downturns.

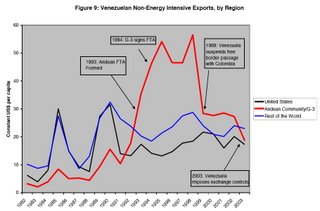

From this point of view, policies that help diversify Venezuela's export basket constitute a safety net against future downturns. And few policies had achieved that goal as well as signing regional free trade agreements like the Andean Community and the G3 deal with Mexico and Colombia. As this chart shows, from the early 1990s Venezuela's non-Energy Intensive producers finally started to gain a foothold, largely thanks to those deals:

As the chart also shows, since the very start of the Chavez era, misguided trade policy decisions have seriously undermined the value of those agreements. All of which we should keep in mind as we track the debate over Venezuela's exit from the G3 and the Andean Community, and our entry into the barely-functioning Mercosur.

First off, Venezuela's Andean and G3 trade was largely concentrated on its largest and most "natural" trade partner: Colombia. Tearing down our trade agreements with Colombia to enter a deal with countries whose economic center of gravity is thousands of miles away makes no sense.

Second of all, while it's clearly a bad idea to formally deny Venezuelan exporters their privileged access to the Colombian market, we need to keep the decision in perspective: the real economic damage has already been done, through things like the introduction of transshipment requirements in 1999 and exchange controls in 2003. Formally exiting the deals merely makes it official.