My “commute” took me right by PDVSA headquarters on Avenida Libertador, twice a day. But this was late 2002 - and, as you'll remember, during the oil strike a group of chavistas decided to camp out more or less permanently in front of PDVSA - a sort of “rojo, rojito” counterpoint to the generals of Plaza Altamira. So twice a day, every day of the week, I had to walk straight through this little throng of militant chavistas just so I could get to the office where I'd spend the rest of my day criticizing them.

Looking very much like the antichavista sifrino I am, this experience was more than a little disconcerting. Pretty soon, I realized I would need some camouflage. Rummaging through the wares the street-vendors at the camp were peddling, I found this bandanna:

Looking at it sideways, I realized I kind of liked it. It dawned on me that this was the only chavista slogan I actually agree with. After all, by December, 2002 - with Globovision playing "Y deciiiiiimos siiiiiii a la esperanzaaaaaa!" on a continuous loop all day long - I was sure the opposition had gone off the deep end. This was a chavista slogan I could make my own!

So for months on end I wore this silly thing on my head on my way to work. There was something appealingly ironic about having to wear it for my own protection. I felt like I was playing a secret joke on the government, like their attempt to impose a new identity on me was as crazy as the ribbon claimed Chavez was making me. I could laugh about it because I was certain that, though they might be able to dictate what I put over my head, they will never control what’s in it.

An identity under siege

“Chavez makes them crazy.” When you think about it, it's a really odd slogan. Where else do you find a leader who boasts about undermining the mental health of his opponents? Why is this something to brag about? What does it say about Chavista values that managing to get under our skin is actually a cherished revolutionary achievement? And what is it about Chavez, in the final analysis, that's driving us crazy?

I think Katy came close to answering this the other day when she noted that:

Chávez knows we fear him. That's why his speech is so hateful, so full of incitement. He works to ignite our fear and makes us appear... well, fearful, or to use another word, squalid. It's a show put on for the benefit of poor voters who get a kick out of watching us tremble. It's like their own little French Revolution is playing inside their head; Chávez's tongue playing the part of guillotine.Part of what's driving us crazy is the realization that Chavez actually gains politically when he baits us - that the more he puts us down, the more his supporters get off on it. Strident divisiveness is not part of Chavez's political strategy - it is his strategy.

There's an element of symbolic warfare at play here. Driving us crazy is important for chavismo because it's part of a strategy to "resignify" the country.

This is a word I’m borrowing from pollster Oscar Schemel, who said:

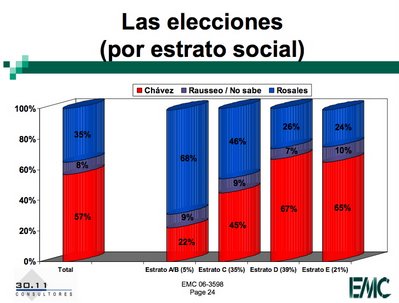

The current political struggle is chiefly over interpretations and meanings. While the elites and the middle class fight to impose their own notions about democracy and citizenship, the poor majority, chavista and non-chavista, is refuting and resignifying those same ideas. A new culture is emerging, and it's resignifying and deactivating our received ideas about politics, amidst a social and symbolic struggle to redefine democracy, development and social relations.Regardless of what we may or may not think will happen in December, beyond the polls and predictions and allegations, there are two things I have learned this week. The first is something we can all agree on, that Rosales still has a shot, because the only poll that counts is the one in December 3rd. The second is more controversial, and it’s that most of us would find it incredibly difficult to deal with the possibility that there may be more of “them” than there are of “us.”

The reasons for this go back to Chávez himself. Because Chavez's attempt at re-signification is, in the end, an attempt to redefine our identity, to change who we are.

The attempt isn't subtle. From changing the national coat of arms to adding extra stars to the flag to splashing a partisan tag across our damn passports and cédulas, the revolution has not been bashful in its attempt is to enshrine its ideology, its phraseology and its iconography permanently into the symbolic fabric of our national identity. The goal is to establish chavismo as the ideology of the State and not merely of the government - partly, of course, by erasing the distinction between the two.

Chavismo's symbolic agenda is fundamentally exclusionary - it is about excluding us, subduing us, about banishing our values, our thoughts and our understanding of what democracy is and how it should work. Its goal is to impose a new symbolic order where the way we think is "un-Venezuelan." What's serious, what drives us crazy, is that Chavismo has launched a bold and ruthless drive to redefine "our" national identity in terms that expressly exclude “us” from it.

Is it any wonder the guy is driving us crazy? Is it any mystery why his supporters are proud of that?

Become the majority right now!

My fellow bloggers and I have been getting some very strong, deeply emotional reactions in the last few weeks from committed readers, people we respect and value and spend lots of our time writing for. What is curious is that what sparked this controversy is something that wouldn’t be that controversial in a working democracy: our honest opinion, based on research that may or may not be right, that more people may be planning to vote for one candidate than for another.

What's clear is that, for many in the opposition, the proposition that we might be in the minority is an impossibility; a banned thought, something unsayable, unthinkable - certainly unbloggable.

Why are we so touchy about this? I think Katy's right: deep down, we are dead scared of losing the battle over the meaning of Venezuelan-ness. Our understanding of democracy, which we had always taken as the unchanging center of our national identity may be about to die...and we've convinced ourselves that it will die, if it turns out that we are in the minority at the end.

Suddenly under siege, feeling itself dependent on majority support for its viability, our identity has turned defensive. Paraphrasing, J.M. Briceño Guerrero, our certainty of being a majority has turned oddly defensive...

it's as though we were speaking rather in the imperative: "be the majority" - layered over an unspoken "it would be unbearable not to be so", all of which rides on the strongly repressed sense that "horror, we aren't!", which only bolsters the imperative: "become the majority right now!" which again turns into the indicative, now supersticious and magical: "we are the majority."We have fallen into a trap, believing that if there are more of them than there are of us, Chavez's attempt to resignify Venezuelan-ness has succeeded. It’s as though contemplating the possibility that more people want to vote for Chavez than for Rosales is contemplating, symbolically speaking, our own ethnic cleansing - the anhiliation of our identity.

But we’re wrong about this. Who we are, what we are, our right to be dissenters and fully Venezuelan at the same time can be sustained even if we are in the minority. A new, exclusionary definition of Venezuelan-ness cannot be sustained over the active resistance of just under half the country; it’s just that we act as if it could. Only the belief that this election is a matter of survival leads us to say things like “everything is in play this December.”

Well, everything is not in play. Don’t get me wrong, this is an important election, one that we really, really need to win. But if we don’t, we will continue our struggle. Unless, that is, we lose the battle inside ourselves; we start wearing our bandannas on the insides of our heads.

In the end, I got so attached to this little trinket, to this souvenir of my struggle to survive amid the symbolic onslaught, that I brought it with me when I came to Europe. I like to glance at it when JVR starts baiting us for the cameras, when Chavez starts to rant. It reminds me that the more we lose our cool, the more we advance their agenda.

In the end, I got so attached to this little trinket, to this souvenir of my struggle to survive amid the symbolic onslaught, that I brought it with me when I came to Europe. I like to glance at it when JVR starts baiting us for the cameras, when Chavez starts to rant. It reminds me that the more we lose our cool, the more we advance their agenda.Because when the other side's goal is to make you crazy, the only way to fight back is to stay sane.